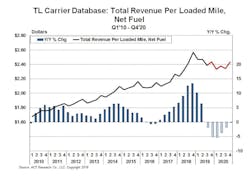

COLUMBUS, IN. Truckers comparing revenue this year to 2018 likely won’t feel better, but there’s still plenty of freight to be moved, according to the load data from DAT Solutions. The problem, explains DAT Market Analyst Peggy Dorf, is that truck capacity—prompted by a couple of very favorable years—has grown even faster.

“We saw 7% more van loads moving the first half of 2019 on the spot market than in the first half of 2018. We're still kind of surprised and you may be as well,” said Dorf, speaking this week at an ACT Research seminar. “But the load-to-truck ratio went into a ditch and spot rates followed.

“Rates are really dependent on capacity, much more so than freight volume.”

ACT VP and Senior Analyst Tim Denoyer runs some different numbers to conclude there’s more at play than just overcapacity, however.

“For-hire freight is in a recession,” Denoyer said. “But it is very important to differentiate [the freight market] from a broader economic recession. The economy is still chugging along fine.”

While’s DAT’s spot market freight activity has largely remained positive, Denoyer cites Cass shipment data that indicates loads fell in each key ground mode: TL, LTL, intermodal and carload rail.

Behind the for-hire freight slowdown, Denoyer points to trade policy and a related manufacturing slowdown, inventory levels and the continued growth of private fleets. He projects a return to freight growth by the second quarter next year, though that timeline comes with a couple of caveats.

First, supporting Dorf’s over-capacity thesis, the Class 8 tractor build is running at near-historic levels, and active tractor capacity is up 10% from the 2018 low point and still growing. And while tractor orders are down, production and sales have not yet responded—so capacity “rebalancing” has yet to begin, Denoyer explains. Simply, carrier profits are down compared to the 2018 boom—but they’re still making money and taking delivery of trucks from the order backlog.

Paradoxically, Denoyer points out that equipment purchasing cuts would pull forward the next spot rate upturn, meaning that truckers need to stop buying new trucks for a while so they can make more money and then buy more new trucks during the next upturn.

Denoyer’s freight outlook also includes an out: If trade wars escalate and lead to recession, then all bets are off. He also points to a possible misleading upturn later this year, as international shipments surge to get ahead of new tariffs.

Also of note: The rate recession is just beginning in the less volatile contract freight market, and will continue through at least first half 2020.

“But the positive news here is that freight cycles are much shorter than economic cycles,” Denoyer said. “They tend to go up for about two years and down for about one year. This one's been going on for coming up on a year, so we should be through some of the cyclical effects that have been driving this down. And I do think that assuming the macroeconomic forecasts are correct, then at some point 2020 will get back to a decent level of freight growth.”

Yield curve

Indeed, contributing to an optimistic outlook, ACT Principle and Industry Analyst Jim Meil makes the case that there is a 2 in 3 chance the current slow but steady expansion, now running at just over 10 years, will continue unabated.

“It will be different this time,” he said, introducing his economic forecast. “We can extend this economic expansion out for another five years, which is no small feat given the fact that we're on record territory right now.”

Despite recent business media headlines about the flattening “yield curve”—a finance measure that’s widely accepted as a reliable warning sign of a coming recession — Meil argues that important real-world indicators are holding their own: Banks are extending credit to businesses; households are not burdened by debt service payments; inflation is under control, giving the Federal Reserve flexibility; and the slow pace of growth of the current expansion enables “policy gradualism”—taking out much of the risk of a misstep in managing the economy.

Potential “shocks” that could send slowing GDP growth into negative territory for a couple of quarters are largely tied to rising global risks. But there’s nothing on the horizon that compares to the Gulf War or the housing collapse that led to previous recessions. Meil also notes that next year’s election will create business uncertainty, and a decidedly left turn in the White House and Senate could signal investment trouble.

“We think there are enough things on the positive side of the ledger to say this thing will go on,” Meil concluded, before noting his 1 in 3 chance that the economy will stall. “If you get that problematical trigger event with a vulnerable US and global economy, that spells trouble.

“And again, I love a party. But all good things must come to an end.”

Coyote curve

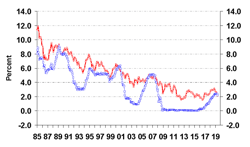

Interestingly, unlike the broader economy, freight rates cycle with the predictability of ocean tides—if you have the model building chops of Coyote Logistics Chief Strategy Officer Chris Pickett. Indeed, if the Coyote Curve — Pickett’s forecast framework—is to be believed, it’s almost as if the freight rate cycle existed independently of the economy. The 15-year chart is compelling in its regularity. The only unsightly bumps in the sine wave are the result of shocks not from Wall Street or Washington, but from Mother Nature: hurricanes. But, ultimately, even natural disasters don’t seem to interfere with the regular rise and fall and rebound of freight rates.

Perhaps validating the company’s forecasting ability, Coyote—a 3PL acquired by UPS in 2015—has grown into a $4 billion business in no small part by anticipating swings in the freight market better than most, and pricing their services accordingly.

Indeed, when it was first published during last year’s historically tight capacity and high rates, the Coyote Curve indicated the market was already past the peak. Improbable as it might have seemed at the time, the market actually fell even faster and harder than the forecast.

The good news for truckers and transportation equipment manufacturers is that the Coyote Curve indicates the truckload spot market has reached an “inflection point” in the downturn.

“What is consistent [in the model] is the time between when we hit our inflection points in terms of the maximum point of deflation, when the market actually turns from net negative to net positive,” Pickett explained. “And the reality is once we hit the inflection point, no one's really feeling it or talking about it until you actually flip. And then after two quarters, it's, ‘Holy cow—what happened?’

“Does it happen with this much regularity? It doesn't feel like it. We all have short memories. But the data would suggest that it does. So simply it’s two to three quarters, plus or minus, from our inflection point when the market flips. This is consistent. You can set your watch. I can't tell you how high it's going to go or how low is going to go—we’re not there yet—but I can tell you lots of interesting things.”

Pickett emphasizes the forecast doesn’t need to be perfect: The point is to anticipate the swings to better manage market volatility.

“We feel the euphoria then pain, euphoria, pain—and we never learn,” Pickett said.

Freight trends

Doing the math on supply and demand or predicting future rate trends from a historical model certainly helps carriers manage market swings, but hauling freight is still the reason trucking companies exist.

DAT’s Dorf, in outlining freight trends, explains the “3 Es,” or the structural forces now driving the market, independent of seasonal swings and macroeconomic forces.

1. E-commerce and consumer purchasing in general:

- Strong indicators for consumers: near-zero unemployment, increased wages, and lower taxes mean more purchasing power

- E-commerce continues to be disruptive because of its rapid growth – we had a big spot market volume bump in July, which was different from the typical trend; and

- The growth in e-commerce may slow, but it’s not reversing.

Also, the last-minute and last-mile deliveries are re-shaping supply chains, changing seasonal patterns, and accelerating demand for ever-higher transportation service levels.

2. Energy:

Dorf contends that domestic energy production is “all upside,” even when the sector is in a lull. There are 12% fewer wells this year, and each well requires 1,000 truckloads of sand, chemicals, and equipment—so any cutback has a big impact, especially for flatbed. On the other hand, she notes, Chevron and Exxon announced major new investments in the Permian Basin. That means a long-term boost for freight—especially flatbeds—as well as employment.

“Overall, the fracking revolution is not going away,” she said.

3. ELDs:

The electronic logging device mandate was a significant factor in the capacity crunch that peaked in 2018 as trucking productivity suffered. A second round that requires fleets to retire older e-log technology (AOBRDs) has a Dec. 16 deadline. The transition entails a certain amount of driver re-training, Dorf adds, but otherwise she doesn’t anticipate major problems.

Still, the impact of ELDs—which severely limit a driver’s ability to run beyond the legal limits—has widespread and lasting impacts. Specifically, Dorf points to loading dock practices, and the relationship between the carrier who needs to drivers moving, and the shipper or consignee who might not value a driver’s time.