The 2020s seem destined to be a decade dominated by grand ambition, where the transportation industry will swing for the fences with new technology. Autonomous driving has the deeper implications on safety and personnel, though vehicle electrification will likely get the most attention from fleets. From the production and piloting of battery-electric vehicles and fuel-cell electric trucks, to installing charging infrastructure and obtaining incentives, every organization that uses commercial vehicles will need to deal with the topic sooner rather than later.

Because of mounting regulations, public demand, and financial advantages, such as lower fuel and maintenance costs, fleets will feel the pressure to replace internal combustion engines in their lineup and hit an electrification home run. But is this the most optimal strategy right now?

With their sights transfixed on an unknown and unproven future, opportunities for immediate improvement can be missed in the present. While particulate matter (PM) has dropped 43% from 2000 to 2019 in the U.S., 47,800 deaths were attributed to PM, according to the Health Effects Institute. That's 23% more deaths than from fatal accidents in the same year.

If the ultimate goal of electrification is to reduce emissions to improve air quality and reduce the impact of climate change, can the world afford to wait several years and possibly strike out?

There’s no need to wait for electric vehicles (EVs), which currently account for a few percent of vehicles on the road and may own 30% of the new market by 2030; change can happen right now, according to experts in the field of idle reduction technology (IRT). They believe much of the idling done by commercial vehicles can be eliminated through equipment and education, thus reducing a large source of emissions.

“By investing in technologies and practices, fleets can reduce idle to well below 20%,” asserted Mike Roeth, executive director for the North American Council on Freight Efficiency (NACFE), in the organization’s 2019 Confidence Report on Idling. “The challenge is figuring out which set of technologies are best for you and being diligent in making it work.”

The key is to reduce idling when the opportunity presents itself. For instance, trucks stuck in traffic could employ an engine start-stop system or utilize a bunk heater overnight in a Class 8 sleeper, which can noticeably reduce emissions today. Compare this to the planned adoption of EVs, which will represent only a tiny fraction of fleet emission reductions for many years. California, the most progressive state on emissions, is targeting 1.5 million zero-emission vehicles by 2025, representing 5% of the total 29 million vehicles. The state consumes 52 million gallons of fuel a day, and every gallon saved from idle reduction will not end up as greenhouse gases and PM.

There’s financial motivation as well. Slashing idling lessens fleets’ fuel and maintenance costs. It’s also the law in 23 states, most notably California, with 18 of those states offering grants, loans, tax credits, or pilot programs to proliferate the technology.

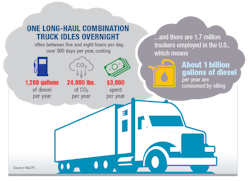

The problem is so big, even these measures may not be enough. According to the Argonne National Laboratory, idling personal and commercial vehicles in the U.S. consume 6 billion gallons of fuel annually at a cost of $20 billion. Based on U.S. Energy Information Administration data, the U.S. used 47.2 billion gallons of diesel and 142.7 billion gallons of gasoline in 2019.

To people like Allen Schaeffer, executive director of the educational nonprofit Diesel Technology Forum, the best way to rally and achieve true transformative change is through incremental improvements.

“It's not going to be the grand slams or home runs that win games; it's consistently hitting singles and doubles,” said Schaeffer, who has been in his role for more than 20 years. “That is exactly what the trucking industry has done over time.”

Most notably, due to regulatory mandates, the heavy-duty sector eschewed the older engines that spewed black smoke for ultra-efficient powertrains with diesel particulate filters (DPFs) and exhaust gas recirculation systems. From 2007 to 2019, Schaeffer estimated this change eliminated 126 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2), 18 million metric tons of nitrogen oxides (NOx), and 1 million metric tons of PM. It also saved 12.4 billion gallons of diesel.

The previous impact of idling, and its resulting emissions, can’t all be eliminated, but with a balanced attack of technology and education, fleets can score some small victories each year. Fleet fuel costs are only the beginning.

NACFE found a 10% annual reduction equals 1% in fuel economy, or $500 to $700 annually with $3/gallon fuel prices and 100,000 miles/year.

“You start adding up those little bitty changes, 1% or 2% here and there, and all of a sudden you’re starting to get some real numbers,” Schaeffer said. “Factoring incremental improvements in things as simple as idle reduction across an entire fleet of vehicles, and those numbers start to run up into the millions [of dollars].”

Reducing idling is also a strategy available to every fleet with fossil fuel vehicles — and one that can have dramatic results. Several technologies now exist to address these issues, with 83 verified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) SmartWay program.

The American Trucking Associations estimated that idling doubles the wear and tear on engine parts versus normal driving and adds $2,000 per truck annually. Furthermore, utility company Altech found utility vehicles idle in park for 65% of their “engine on” time, and each hour equals an equivalent 25 miles of driving.

The technology

Successful fleet managers and owner-operators savor the “small ball” aspect of trucking by looking at the data leveraging every edge.

On the road, this may include aerodynamic fairings, low rolling resistance tires, and high-efficiency powertrain yield. But if they overlook how much is spent idling, all that effort goes to waste.

This is the case when a long-haul trucker trades the driver’s seat for the bunk and leaves the engine running to heat the cab. A stat often associated with Class 8 trucks fuel consumption is “1 gallon consumed per hour of idling,” though Schaeffer asserted that while that may have been true prior to modern EPA regulations on greenhouse gases, the latest engines use two-thirds or three-quarters of a gallon. “But still, that's real fuel that costs real money, and real emissions are being created,” he added.

And idling overnight (or day, depending on the shift) might not have been too bad when diesel was less than $2 a gallon, which last occurred in 2016. That’s $16 for eight hours of sleep. This March, average U.S. diesel costs crossed the $3 threshold, a 60-cent jump from October 2020. In these conditions, a driver who sleeps 200 nights in a truck that uses three-fourths of a gallon will pay $3,600 for the heated slumber.

Bunk heaters, which have about a 70% take rate for Class 8 sleepers, according to leading manufacturers, use a fraction of a gallon for a whole night.

“You're talking about pennies on the dollar in terms of return on investment per night,” said John Dennehy, vice president of marketing and communications for Eberspaecher Climate Control Systems. He noted the Espar Airtronic D2 bunk heater costs less than $2,000 and has evolved over four generations since 1997. The Airtronic gets 16 hours per gallon of diesel fuel.

Two years ago, Webasto, released the Air Top 2000 STC, which consumes one gallon of diesel fuel every 22 hours. Saving at the pump is only the beginning.

“Our customers are finding if they are idling, it's causing a second pain because excessive idle makes that DPF fail faster, or needs to be removed and cleaned or replaced,” noted Don Kanneth, Webasto director of aftermarket sales for North America. He said just to get the DPF looked at can cost $500 and several thousand dollars to be replaced, in addition to incurring downtime. Because of that, Kanneth said day cabs that are often stationary are also employing air heaters.

Both companies also have coolant heaters, oil-fired devices that warm coolant and bring the engine up to 165 degrees F, as opposed to raising the temperature through traditional engine idling.

“A Webasto Thermo Top Evo, for example, can run for 10 hours on a single gallon of fuel,” said Dan Erck, regional sales manager at Webasto. “Considering that you only need to operate the coolant heater for 30 to 40 minutes prior to engine startup depending on ambient temperature, this could save a fleet thousands of dollars in fuel costs alone.”

Engine heaters also reduce DPF wear and tear. Webasto found that in a cold engine, the Thermo Top Evo removes 67% of particulate matter out of the air stream before it reaches the DPF. At 75 degrees F, that is a 40% reduction.

To run the air conditioning and other cab accessories, fleets can also rely on auxiliary power units (APUs). Diesel and electric APU options are available.

“Running a Tripac Evolution APU to provide the driver with cooling, heating, and tractor battery recharging uses about 80% less fuel than running the much larger tractor engine,” said Jim Flaherty, Thermo King senior product manager for APUs. “Over the standard life of an APU, this equates to about 12,500 gallons of diesel fuel saved and 127 metric tons of carbon dioxide avoided.

In total, Flaherty reported the annual Thermo King APUs shipped cut about 2.7 million metric tons from entering the atmosphere. These devices weigh about 500 lbs., and some states offer a GVWR exemption to offset the weight, so it does not count against payload.

In its idle report, NACFE advised “the most efficient and effective idle-reduction solution for a fleet entails a combination of complementary technologies used together,” such as bunk heaters and driver controls.

Owner-operator Bernie Gray can attest to that, as he has seen a huge difference by combining the Kenworth Idle Management System (KIMS), a driver control panel paired with four batteries under the passenger seat, and the Espar Airtronic.

His profit margin has reaped the benefits. The short hauler, who comes home on weekends, had spent $45,000 on fuel in 2018 with his 2017 W900, which had no idle reduction systems in place. In 2020, with the IRT combination, he spent $30,000.

In warmer weather, Gray does idle to “cool the whole inside of the truck with the engine power to help save wear and tear on the KIMS.”

While the 30-year trucking veteran is no longer a company driver, Gray said these are effective retention and recruitment tools. “If a company didn't have that, then I don't know if I could actually work for them,” he said.

Running up the score

While each driver can save big, the bigger the fleet, the more runs those small incremental changes can drive in. When George Survant was the senior fleet director at Time-Warner Cable, the private fleet comprising 19,000 light- and medium-duty commercial vehicles participated in a fuel research program in which the data loggers revealed 39% of the fuel burn was going to idling. And the fleet used 25 million gallons per year.

The fleet’s Ford Transit Connect vehicles operating in Manhattan were getting 12 mpg, while normal city driving should have been closer to 22 mpg.

Survant, an expert in sustainable fleet strategies with more than 40 years in fleet management, installed start-stop engine technology in the vehicles, which shuts off the engine when the brake is fully depressed, such as at a stoplight.

“By the time you take your foot off of that brake and go to the gas pedal, the engine is humming along nicely and off you go,” Survant said. “It's a little disconcerting the first time; you think [the vehicle has] stalled.”

Other changes included engine control module reprogramming and switching to small-bore diesel engines.

By intermittently cutting idle time, Survant said the cable company’s fleet saw a noticeable difference, reducing fuel burn by 11% year over year. After the changes, even full-size pickups were getting 16 mpg.

“That was not only a proportionally huge amount of improvement but in terms of being able to keep the same payload, the same truck dimensions, that was a huge advantage,” he said.

Changing hearts and minds

In addition to consulting, Survant now works in an advisory capacity with GoGreen Communications, a Canadian-based company that certifies fleets in idle reduction training, because "of its very well-crafted behavioral modification approach."

One specific reason is that CEO Ron Zima appeals to fleet drivers by making them aware of the adverse effects of personal idling habits, which then seeps into their professional behavior.

At training sessions, Zima shares his own personal experience, explaining how he was a notorious idler himself, accruing 185 idle hours a year. This could be preheating his engine with a remote starter 40 minutes before the end of the workday, as well as outside of the hockey rink where his children practiced.

“As a parent, I noticed how much everybody was idling outside the school, and inside the school, my kids were learning about climate change, health, and math, and the exhaust was so bad,” he recalled, adding the principal noticed the emissions from idling buses waiting to take the children home would make the faculty feel lightheaded.

He saw anti-idling laws were in place, but largely ignored. Zima worked in his own city with fleets at the ports and ground services, and within four months, he said idling was reduced by 40%.

Data is the first component to transformative change, as fleets first need to see the issue. Survant projected about 70% of fleets don’t look at idling data. That’s why installing telematics devices should be the first step.

In 2013, an idle-reduction advocate in Vermont named Wayne Michaud worked with the American Lung Association to get NexTraq GPS systems in Burlington, Vt.-based FairPoint Communications’ fleet of 1,200 trucks. By measuring the data, training drivers, and following up with those who do not comply, the company reduced idling by 30%.

FairPoint would monitor excessive idling, and fleet trainers would coach drivers on when to turn the engine off, said Jay Mullen, operations manager at FairPoint, which is now Consolidated Communications.

Michaud also helped push for Vermont’s anti-idling laws, which limit idling to under five minutes per hour. He currently runs Green Driving America, which focuses more on electrification.

The second component is education. Zima developed a program called “Idle Free for our Kids for Fleets,” an online course that he said “emotionally pulls drivers in like no other driver training, with values and messaging that they often respond passionately to.”

Myth-busting is another tactic. Zima often has to explain idling creates more wear and tear than engine start/stops. According to Cummins, idling leads to higher fuel contamination of lube oil and cylinder wall wear, contributing to a 20% engine life reduction.

He said vocational fleets have high completion rates in the program, which is fortunate for those managers, as Alltech found vocational fleets spend nearly two-thirds of engine time idling.

With as many people as he’s trained, Zima pondered why the low-hanging fruit of idle reduction has not gotten more traction.

“You have this massive disconnect within the market right now,” he said, with more industry attention and political juice going to the hope that “EVs and electric trucks will save us in the next five years.”

Meanwhile, Zima added, idle reduction “is not dependent on replacing vehicles to get a success rate that’s measurable.”

Survant also notes the benefits on the environment and air quality are indisputable. However, the best way to inspire change in fleets is addressing the bottom line.

“Whether it's going to melt the polar ice caps or not, I'm not enough of a scientist to know,” he said. “But what I do know is idling improves the reliability of my fleet, reduces the amount of fuel I burn, and puts money back into the corporation.”