Trucking industry reacts to GHG3 rule pushing zero-emission adoption

The Biden Administration’s Environmental Protection Agency finalized new heavy-duty vehicle emissions rules for model years that push manufacturers to sell more zero-emission trucks in the coming years, despite pushback from trucking groups that say the law is too narrow and unattainable.

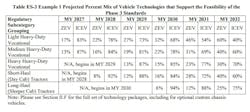

A percentage of each manufacturer's total vehicle sales must be converted to zero-emission vehicles every year. By 2032, the rule aims for a quarter of new long-haul and 40% of heavy-duty short-haul and medium-duty vehicles to be zero-emission.

Trucking and manufacturer groups called the new rules unrealistic, while environmental groups said they don’t go far enough. The Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards for Heavy-Duty Vehicles—Phase 3 builds on EPA’s GHG Phase 2 program from 2016. In its filing, the EPA notes the new “standards are technology-neutral and performance-based, allowing each manufacturer to choose what set of emissions control technologies is best suited for them and the needs of their customers.”

American Trucking Associations, the largest trucking industry trade organization, said the rule’s unattainable targets will hamper U.S. supply chains.

See also: Diesel’s dominance continues as trucking plans clean energy shift

Trucking industry reacts to GHG3 standards

“ATA opposes this rule in its current form because the post-2030 targets remain entirely unachievable given the current state of zero-emission technology, the lack of charging infrastructure, and restrictions on the power grid,” Chris Spear, ATA president and CEO, said. “Given the wide range of operations required of our industry to keep the economy running, a successful emission regulation must be technology-neutral and cannot be one-size-fits-all. Any regulation that fails to account for the operational realities of trucking will set the industry and America’s supply chain up for failure.”

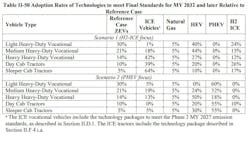

Despite lower zero-emission vehicle rates set for 2027-29 model years, ATA believes that the mandated zero-emission vehicle penetration rates in later years will primarily stimulate investment in battery-electric and hydrogen technologies, limiting fleets’ choices with unproven technology.

GHG Phase 3 requires that each heavy-duty vehicle manufacturer convert an increasing percentage of their total vehicle sales to zero-emission vehicles annually.

Jim Ward, president of the Truckload Carriers Association, wants stakeholders to understand how much progress the trucking industry and members of his trade group have already made to reduce emissions. Emission-reduction technology has already led to more expensive diesel equipment that is essential to U.S. supply chains.

“The industry has effectively reduced NOx and particulate matters through the evolution and implementation of new technologies and remains committed to being a good steward of the environment,” Ward said after the rule was announced. “The journey ahead provides for many alternatives to be considered to lower carbon such as blended biodiesel, renewable natural gas, diesel-electric, just to name a few, to help us bridge the gap to the future. We cannot just sit idly by and watch the implementation of a policy that will have a significant impact on our members’ business.”

According to ATA, modern diesel equipment is nearly 99% cleaner than trucks operating a generation ago. With more than half of Class 8 trucks operating in California pre-dating 2010 emission regulations, ATA has been pointing out that upgrading those trucks to modern diesels would reduce California fleet emissions by 83%.

“We can cut emissions—starting right now,” Spear said during his address to ATA members during its management conference last fall. “This would save lives by putting the safest equipment on our roadways. And it would support jobs—union jobs, which I understand is a major priority for the most pro-union president in American history. Truth is, there is something in this for everyone. And most important of all, our solution is achievable—no rainbows, no unicorns needed.”

On Friday, the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association reiterated the group’s opposition to EPA’s “latest assault on small business truck drivers.”

“Small business truckers, who happen to care about clean air for themselves and their kids as much as anyone, make up 96% of trucking. Yet this administration seems dead set on regulating every local mom-and-pop business out of existence with its flurry of unworkable environmental mandates,” OOIDA President Todd Spencer said. “This administration appears more focused on placating extreme environmental activists who have never been inside a truck than the small business truckers who ensure that Americans have food in their grocery stores and clothes on their backs.”

In official comments filed to the EPA last June, OOIDA outlined issues related to costs, the timeline, safety concerns, and operational problems. Among its basic objections, OOIDA argues that rushed and difficult-to-achieve mandates, along with associated higher purchase prices and operating costs, “force drivers to stick with their older trucks rather than buy new ones.”

According to the organization, the EPA Phase 3 rule is one of four key regulatory actions taken by the Biden Administration that, if allowed to take effect, could potentially “put untenable pressure” on small business truckers.

OOIDA also challenges the BEV adoption mandate, noting the absence of a national charging infrastructure network for heavy-duty trucks.

“Professional drivers are skeptical of BEV costs, mileage range, battery weight and safety, charging time, and availability,” the filing states. “EPA must consider a more feasible implementation timeline that would provide reliable and affordable heavy-duty vehicles for consumers, particularly small trucking businesses and individual owner-operators.”

See also: $1 trillion price tag on electrifying U.S. trucking industry

EPA lays out its case for cleaner trucks

In the final rule published March 29, EPA responded to opposition by saying it believes it's essential to balance the need to reduce GHG emissions for public health and well-being in the long term with the time needed for manufacturers to develop, make, and sell new products and build zero-emission infrastructure in the short term.

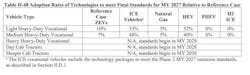

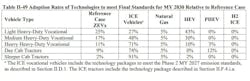

Regulators decided to make the GHG emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles less strict for all vehicle types in model years 2027-30. The final standards will grow stricter slower than the EPA first proposed. Day cab tractor standards start in 2028, and heavy-duty vocational vehicle standards start in 2029. The final standards for sleeper cabs begin in 2030 but are less strict than initially proposed for 2030 and 2031. They are equally stringent to the proposed standards in model year 2032.

According to the Biden Administration, these new GHG3 standards give trucking more certainty while catalyzing private investment, supporting U.S. manufacturing jobs in advanced vehicle technologies, and invigorating and strengthening the U.S. economy.

“In finalizing these emissions standards for heavy-duty vehicles like trucks and buses, EPA is significantly cutting pollution from the hardest-working vehicles on the road,” EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan said. “Building on our recently finalized rule for light- and medium-duty vehicles, EPA’s strong and durable vehicle standards respond to the urgency of the climate crisis by making deep cuts in emissions from the transportation sector.”

EPA’s latest modeling shows that the final standards will result in greater pollution reductions than the proposed rule while providing more time and flexibility for manufacturers to develop, scale, and deploy clean heavy-duty vehicle technologies. The 1 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions avoided by these standards are equivalent to the emissions from more than 13 million tanker trucks’ worth of gasoline. With this action, the Biden-Harris Administration is continuing to deliver on the most ambitious climate agenda in history while advancing a historic commitment to environmental justice.

New analyses by the EPA support its conclusion that the final rule sets GHG standards for model years 2031 and 2032 that are possible and appropriate.

See also: New freight corridor strategy maps future of zero-emission fleets

‘Uncertainties lie ahead’ for fleets and manufacturers

The Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association, representing major commercial vehicle makers, noted that its members are committed to trucking’s decarbonized future.

“We all are working toward the same common goals and desired end results,” Jed R. Mandel, EMA’s president, said. “To ultimately be successful in transitioning to a commercial vehicle ZEV future, all parties need to be better aligned on the realistic timing for delivering the products and infrastructures critical to achieving the successful outcome we all want.”

Mandel said his group will continue to work with EPA and other regulators in the Departments of Energy and Transportation and other stakeholders to make GHG Phase 3 a success.

“However, it is important to note that uncertainties lie ahead,” he said. “Long lead times and other actions beyond the control of the manufacturers, and beyond EPA’s control, are needed to assure the infrastructures essential to operating heavy-duty ZEVs are in place, in time. EPA’s final GHG Phase 3 rule works to erode near-term regulatory certainty and stability by reopening the existing 2027 GHG Phase 2 rule—a rule that we defended against rollbacks—and by assuming a level of ZEV purchasing that appears to be overly ambitious.”

The Clean Freight Coalition, made up of trucking industry groups such as ATA and the Truckload Carriers Association, opposes the new GHG3 standards.

“Today, these vehicles fail to meet the operational demands of many motor carrier applications, reduce the payload of trucks and thereby require more trucks to haul the same amount of freight, and lack sufficient charging and alternative fueling infrastructure to support adoption,” Jim Mullen, CFC executive director said. “In addition, battery electric motorcoaches have a reduced range and capacity compared to diesel buses. These commercial vehicles are in their infancy and are just now being tested and validated with real-world miles.”

The CFC recently commissioned a report outlining the many hurdles to electrifying the entire commercial trucking industry.

Roland Berger's CFC study found that converting entirely to battery-electric vehicles would cost the industry nearly $1 trillion. That price only covers infrastructure and utility upgrades. It does not include the costs of electric trucks, which can cost more than twice as much as traditional diesel-powered tractors.

According to CFC's Mullen, a diesel Class 8 truck costs roughly $180,000 compared to $400,000 for an electric truck. Mullen notes that these costs will be passed on to consumers.

Due to various economic and operational constraints, electrification of heavy-duty vehicles presents more significant challenges than that of medium-duty vehicles. A recent study estimates that the average cost of charging infrastructure for fleets will be significantly higher for heavy-duty vehicles, at approximately $145,000 per vehicle. In comparison, medium-duty trucks will require an investment of approximately $54,000 per vehicle.

“The GHG Phase 3 rule will have detrimental ramifications to the commercial vehicle industry, many small and large businesses, commercial vehicle dealers and their customers,” Mullen said.

See also: It’s not too early to think about your fleet’s future power

Environmental backing and concerns

While trucking groups point to the large price tags and projects needed to actually decarbonize U.S. freight—more than 70% of which travels by truck—the EPA claims its plan will eventually save fleets money.

“The HD industry will save approximately $3.5 billion in operating costs (e.g., savings that come from less liquid fuel used, lower maintenance and repair costs for ZEV technologies as compared to ICE technologies, etc.),” regulators wrote in the final rule.

According to government estimates, the EPA’s clean truck standards could reduce one billion metric tons of climate pollution by 2055. They also reduce smog-forming nitrogen oxides by 53,000 tons in 2055.

“Today, the Environmental Protection Agency took another key step in our journey toward a future with less traffic pollution—a future that will deliver cleaner air for our children, healthier communities, and a safer climate,” said Amanda Leland, executive director of Environmental Defense Fund.

Guillermo Ortiz, a clean vehicles advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that the truck tailpipe solution has worsened climate change and public health.

“These EPA standards will help protect our families from dangerous pollution while steering us toward a safer climate,” he said. “This rule could have done more. Our nation needs a vision to eliminate pollution from the freight transportation system. Every wheeze, every gasp for breath in communities impacted by the movement of freight serves as a reminder of the urgency to act. The federal government needs to fully address this scourge on our families.”

On the other side, ATA claims that the EPA’s final rule will drive only battery-electric and hydrogen power developments, which will limit fleets’ choices among early-stage technology that is yet to be proven beyond some regional applications.

See also: Latest oils and lubricants for heavy-duty fleets

“The trucking industry is fully committed to the road to zero emissions, but the path to get there must be paved with commonsense,” Spear said. “While we are disappointed with today’s rule, we will continue to work with EPA to address its shortcomings and advance emission-reduction targets and timelines that are both realistic and durable.”

CFC’s Mullen urged the government to support lower carbon alternatives—such as biodiesel and renewables—instead of focusing only on zero-emission technology.

“These lower-carbon fuels will allow EPA to make progress on emissions today while the industry implements longer-term options,” Mullen argued. “Mandating a transition to technology that is decades away from being viable at scale will keep older, less environmentally friendly commercial vehicles on the road longer, stunting the carbon reduction progress EPA seeks.”

Editorial Director Kevin Jones contributed to this report.

About the Author

Josh Fisher

Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief Josh Fisher has been with FleetOwner since 2017. He covers everything from modern fleet management to operational efficiency, artificial intelligence, autonomous trucking, alternative fuels and powertrains, regulations, and emerging transportation technology. Based in Maryland, he writes the Lane Shift Ahead column about the changing North American transportation landscape.