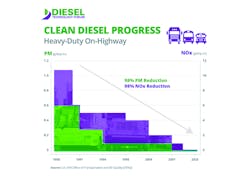

Recently, the Diesel Technology Forum came out with a truckload of positive diesel emissions data that may even offset all those private plane trips celebrities and politicians take to clandestine climate change summits. You can read about them in our piece in Part 1 on the subject, but this one point from the non-profit advocacy group encapsulates the paradigm shift: “Clean” diesel trucks sold today generate 1/60th of the emissions their 1988 counterparts did.

In 2017, medium and heavy-duty trucks accounted for 23% of the transportation sector’s emissions, and the sector itself comprised 29% of the U.S. greenhouse gas total. So diesel’s turnaround is a monumental, chest-thumping achievement.

What makes this even more important is that diesel is the lifeblood of the economy, contributing $4 trillion in economic activity in Q1 2019, or “12% of all U.S. private-sector industrial activity,” the Diesel Technology Forum reported.

“Across the board, today’s generation of advanced diesel technologies are more energy-efficient and lower in emissions than previous generations, and remain the technology of choice in key sectors like commercial trucking, marine and locomotive applications,” said Allen Schaeffer, executive director of the Diesel Technology Forum, to a House environmental subcommittee. “Coupled with growing success using advanced renewable bio-based fuels, diesel engines are well-positioned now and contributing already to low-carbon goods movement in America.”

And a lot of people deserve credit for taking such a samurai sword slash into the shroud of smog hanging over our collective heads. This includes the engineers who tirelessly optimized iteration after iteration, the manufacturing workers who built the engines, and even the executives who loosened the R&D and production budget purse strings to explore new diesel technology.

Then there are the legions of fleet owners who trusted the manufacturers enough to invest in unproven engines. It has been a bumpy road since the 2007 and 2010 EPA emissions mandates, and not every engine maker has deserved that trust. But the industry knuckled down and made it through the government-ordered disruption.

That’s the good news. The better news is that all these modern engines have not only substantially reduced the presence of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and asthma-causing Nitrogen Oxide; these smarter engines are providing significant efficiency improvements to fleets. In essence, the iterative cuts over time have added up to big chunks of inefficiency being lopped off from trucks’ total cost of ownership (TCO). Fuel savings alone save Class 8 trucks about $3,000 annually, according to the Diesel Technology Forum.

Cummins’ development of the 2020 X15 Efficiency Series, which will become available on a limited basis in November, drives this home. The company, which turned 100 this year, says this X15 has the best fuel economy, longest maintenance intervals and uptime in the industry.

It started in 1998 as the ISX15, at the time new 15-liter solution for the heavy-duty truck segment. The design moved to exhaust gas recirculation in 2002, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) in 2010 and has changed fuel in 2013. From 2013 to 2016, base engine improvements led to a 2.8% better fuel efficiency. The product was renamed the X15 in 2017, offering the Productivity Series and the Efficiency Series, the latter of which received a 2.6% fuel efficiency improvement.

The latest version betters that by 5% when paired with the Endurant transmission, made by a joint venture between Cummins and Eaton. The standard improvements still provide a 3.5% improvement.

These engineering changes include an increased compression ratio for combustion optimization, reduced parasitic losses due to changes such as decreased water pump speed, and increased air handling efficiencies (through upgraded turbocharger aerodynamics), explained Kris Ptasznik, Cummins’ X15 product manager.

“No major earth-shattering hardware changes” were attributed to this modest improvement, Ptasznik said.

But small changes add up. No one figured out how to cut emission levels to 1/60th of levels 30 years ago overnight. It probably took terabytes of CAD files and enough coffee to fill the Grand Canyon.

Behavior Changes

OEMs have figured out the hardware for the most part, so the biggest opportunity rests with getting the end-user, the driver, to optimize their behavior.

“There’s a 30% variability from driver to driver doing the same work,” Ptasznik said. “The driver impacts fuel economy a whole lot.”

By enhancing engine software, Cummins has found a way to dummy-proof certain functions by relying on embedded GPS data to prepare the truck for going up or down steep grades, merging onto the highway and how to operate depending on the load.

“While using map data, we know what terrain is coming ahead,” Ptasznik explained.

Here’s what each feature does:

Predictive gear-shifting: Downshifts at bottom of the hill to ascend as efficiently as possible without constant shifitng.

Predictive braking: Even if the driver underestimates the load or misses a speed grade sign, this feature engages max braking from the start for the better control of the vehicle.

Dynamic power: limits acceleration, not torque, based on load to prevent large deviations in performance from grade to grade.

On-ramp boost: This is a safety feature that removes fuel economy controls to achieve safe speed to merge onto the highway, applying max torque when in the top six gears.

Cummins Connected Calibrations also leaves room for software upgrades without visiting a dealer.

Besides improving fuel mileage, this greatly reduces maintenance.

“The less you touch the brake pedal, the less you have to change the brake pads and brake shoes,” Ptasznik said.

Being more gentle on the transmission will improve that component's lifespan as well. Cummins is also aware of basic planned maintenance costs, which could add an extra $400 just due to downtime. So these power trains extend the timing intervals. Oil changes range from 75,000 miles to more than 100,000.

“If we can align our engine maintenance intervals at a time when a truck needs to get grease jobs done on the suspension, then it’s killing to birds with one stone and is least impactful to the customer’s operation as well,” Ptasznik said.

In the next few years, new fuel sources, primarily electric batteries, and hydrogen fuel cells, will become cheaper and more available, but it stands to reason those technologies won’t experience exponential changes. They will be gradual and also require a lot of sleepless nights from engineers, CEOs taking risks, and customer buy-in.

For now, at least we have a proven technology that is easier on the environment and provides a better TCO.

Ptasznik acknowledged diesel won’t be around “for eternity, but “is going to be around for the next decade.”

And in that time, we are going to continue to push and optimize the diesel product as best we can,” he concluded.

For more info on the 2020 Cummins X15 Efficiency and Productivity Series, check out Cummins Booth #7545 at the North American Commercial Vehicle Show from Oct. 28-31.