Trevor Milton is the confident CEO of Phoenix-based Nikola Motor, which has gained a valuation of more than $3 billion in five years for its potential in zero-emission trucking.

Now he says he has even more reason to be bullish: a prototype electric vehicle cell Nikola says boasts “a record energy density of 1,100 watt-hours per kg on the material level and 500 watt-hours per kg on the production cell level.”

The battery is expected to weigh 40% less, cost 50% less on the material side per kWh, and have less of an environmental impact than lithium-ion batteries. A truck using this technology may weigh 5,000 lbs. less than its electric competition.

The cell could increase EV passenger car ranges from 300 to 600 miles, and a fully loaded Class 8 would have a range of up to 800 miles.

Milton called the innovation, which Nikola is licensing to any OEM that wants it, “the single most important advancement in electric vehicle history.” He also added that OEMs have reached out since the announcement.

“We've cycled over 2,000 times on each cell,” said Milton, who equated that to several hundred thousand miles of testing. “And by doing that, now we have enough confidence.”

This month, Nikola acquired a battery engineering team of 15 PhDs and five team members with master’s degrees to help push the breakthrough past pre-production and into a scalable manufacturing model. More information will be announced at Nikola World 2020.

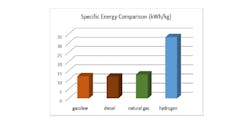

“Normal lithium batteries in the cell levels are about 240 watt-hours per kilogram,” Milton explained to Fleet Owner. “You essentially get double the energy density in the same package in space and weight.”

Nikola won’t reveal the actual makeup of the battery for the next few months, but Milton said the new design eliminated the nickel, cobalt, aluminum, and magnesium — “the bad stuff that stuff is really harmful.”

“Ultimately, by removing a lot of that material in the expensive metals, you reduce the weight, you reduce the material, you reduce the cost, and you're able to store a lot more in the same package,” Milton explained. “Up to this point, no one's ever been able to figure out how to do that. Our teams have figured out how to do that.”

Milton, a Utah native who spent one semester in college before dropping out, is now worth $3 billion, according to Forbes, though his company believes this technology is too important to keep to itself.

“Our idea is that the world has enough problems that one company should not hold that intellectual property and keep it to themselves just for greed,” he said. “There's enough money to be made in this world; it really doesn't matter. We're sold out with our trucks for many, many years. How much more greed can a person have before they're satisfied?”

Death knell for diesel?

The way Milton speaks about his company and technology may sound brash (competitors probably have more colorful descriptors). He invites critics and skeptics jilted by the Tesla Semi’s as-to-yet failure to launch to take their own shots at the unseen technology, but the 37-year-old entrepreneur stands firm on his provocative hashtag, though he’s pragmatic about it.

“Our hashtag 'dieselisdead' is a philosophy; it does not mean that every diesel engine is going to go away today or in the next 10 years,” he explained. “When you get into ships or heavy-duty trucking or rail, I believe diesel is dead in that situation where over the next five to 10 years, it'll no longer make economic sense to ever touch them.”

The diesel industry, which has made great strides in improving its economics and environmental impact, is not likely to roll over and show its belly to the would-be alpha wolf.

“Since 2007, the newest-generation diesel trucks on U.S. roads have eliminated 126 million ton of carbon dioxide, 18 million ton of nitrogen oxides, and 1 million ton of particulate matter, and saved 12.4 billion gallons of diesel and 296 million barrels of crude oil,” said Allen Schaeffer, executive director of the Diesel Technology Forum.

Still, Milton is adamant.

“There's no longer reason to ever be operating or building diesels again. It's done,” he reiterated, stressing the solution for the fleet of the future will either be a hydrogen fuel cell truck (HFCT) or battery electric. “Both of them function now as replacements, and they're now cheaper to operate the diesel.”

Traditional diesel engine manufacturer Cummins is developing both better diesel products and investing in hydrogen as well.

The hydrogen question

Milton pointed out that if this new unnamed battery does what it says, it will also increase the penetration of HFCTs, which could also exploit the cell energy density and size.

“It does actually bring the cost of the entire hydrogen usage and production cost down per kilogram,” Milton said. “A truck running on hydrogen, such as the Nikola Two, could now have a range of 1,000 miles.

“Elon Musk has gone out there and told everyone that fuel cells are ‘fool cells,’ so the whole world believes that,” Milton said. “Hydrogen groups say batteries don't work and they never will — and that's not true either.”

Each will have a prominent place in the zero-emission landscape Milton is painting.

A truck using these batteries would be more for regional hauls and urban deliveries due to the one glaring weakness of lithium batteries.

“The quicker you charge your battery, the more it degrades the battery,” Milton explained. “Some routes require 24/7 operation where they're running trucks all day all night, and they're heavily utilized. That's the wrong application for an electric truck.”

The new Nikola battery would take about an hour to charge, Milton noted, “assuming you have more energy you can put into it faster.” FCETs charge up in 15 minutes.

Milton said the right application for EVs would be making deliveries for three hours and charging before going out again.

Hydrogen trucks are going to be for really weight-sensitive loads,” Milton said. “There's nothing you can do about that with the battery. Even if we reduce half the weight of the battery, you still are not competing with hydrogen on the weight.”

There is still a lot to figure out with the technology, and Nikola’s FCETs won’t go into high-volume production (greater than 35,000/year) until 2023. And for the trucking industry, seeing is believing and no one has yet.

However, Mike Roeth, executive director of the North American Council for Freight Efficiency and organizer of the biennial Run on Less trucking fuel efficiency program, has reason to be optimistic in general, with a good helping of pragmatism.

“The performance, weight and cost curves are producing batteries better than were expected a decade ago,” Roeth said. “We are very early in developing these batteries, so no one knows how far they will go. But all this is very encouraging. Batteries must also live in the difficult trucking environment, so these improvements must also prove reliable and durable with sufficient cycle life.”