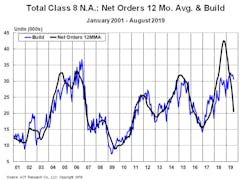

First the good news. The trucking industry has had a great last couple of years. As evidence, Class 8 truck builds in North America are expected to hit 345,000 this year, according to ACT Research. That’s an unprecedented improvement of 51% from 2016. The demand for more trucks means there was demand for more goods to be moved.

Tim Denoyer, ACT Research’s vice president and senior analyst, points to Q3 of 2017 as a watershed moment, as a confluence of factors led to a major capacity crunch.

Along with the booming economy, these factors included ELD compliance taking effect and the damage wrought by Hurricanes Harvey and Maria, which both destroyed trucks and demanded more to aid in reconstruction. He also mentioned the replacement demand created as all the trucks bought prior to the 2007 emissions regulations aging out and ceasing to accumulate miles, going to work on some farm, (quite literally being out to pasture).

“I’ve been covering transportation for 15 years and I've never seen anything like it,” Denoyer said.

This created a void in private fleets’ trucking pools, and they had to shift capacity to the for-hire sector.

“We saw this major increase in spot rates where they jumped to +30%,” Denoyer recalled.

“Big companies were missing their earnings numbers because their shipping costs were out of control so they materially increased the CapEx budgets for trucks,” Denoyer explained.

Unfortunately, after this peak period of record growth, the cyclical trucking industry has only one way to go: down. In its most recent outlook, ACT predicts 2020 will be “a significant correction next year.”

This means an expected 31% drop in Class 8 builds for 2020 to correct for all the extra trucks bought over the last few years.

“By now this ‘regression to the mean’ for 2020 is less a forecast than merely seeing through a pattern already in place, with 2019 net orders year-to-date through the August preliminary tally running at a fraction of the orders pace of the same period in 2018,” said Kenny Vieth, ACT’s president and senior analyst. “It’s pretty clear that the next chapter of this story will not be a happy one, and it will also impact equipment demand in adjacent sectors, such as construction, oilfield and gas, farm machinery, and industrial.”

As pleasantly surprising as the last few years have been, it looks like it’s time for truck OEMs to batten down the hatches.

“When the change comes, it is likely to come fast, and we reiterate what we’ve been saying in recent months: Everyone should be well into their preparations for a rapid downward correction in production levels in the next few months,” said Vieth.

Dark clouds have already gathered to rain on trucking’s recent positivity parade, with manufacturing productivity growing stagnant this summer. Output increased 0.5% in August, according to the Federal Reserve, though the Institute for Supply Management’s September manufacturing index of 47.8, down 1.3 points from August, crushed any hopes of an upturn.

Anything under 50 indicates contraction, and this was the worst mark since the Great Recession a decade ago.

Freight Issues

And Denoyer said the trucking industry already had to contend with a “mild freight recession” in 2019. This may worsen, as overcapacity and low freight demand are lowering truckload and intermodal contract rates.

“While the data are starting to suggest ‘less bad,’ reports suggesting recovery are premature, as key freight metrics continue to trend negative in the latest round of data releases,” Vieth said.

At least until 2022, Class 8 productivity is poised to trend negative:

According to the Cass Freight Index, freight dropped 3% in August year-over-year, which was the ninth month in a row with a negative volume. It was positive for the previous 24 months.

The August 2019 Cass Freight Index Report summarized:

"The weakness in spot market pricing for many transportation services, especially trucking, is consistent with the negative Cass Shipments Index and, along with airfreight and railroad volume data, strengthens our concerns about the economy and the risk of ongoing trade policy disputes."

Spot rates have also decreased (though up this September), which exacerbates the brutal trend of trucking company bankruptcies, which through the first half of 2019 were three times higher than in H1 of 2018, according to Broughton Capital.

So what should the for-hire fleets that planned for higher spot rates do?

“Managing your costs as closely as you can to weather the downturn is probably the best advice here,” Denoyer offered.

And like the downward trend of new truck orders being placed, lower spot rates also forewarn of a slowing economy.

“The lower spot rate is a signal of excess capacity,” Denoyer said, “and the way that gets solved is with drivers going back to other occupations.”

Some positive freight stats could also be misleading, as there was inflated demand before tariffs took effect. There was excess pre-shipping of goods before the Sep. 1 tariffs took effect.

“We don't think this cycle’s quite bottomed out, partly because of this tariff and inventory hangover that we're expecting early next year,” Denoyer said.

And an escalation of the trade war with China could make every current forecast model moot.

“If the President doubles-down from here, a greater global downturn could ensue, with the worst outcomes spreading beyond the impact of tariffs and into a global race to the bottom in terms of currency manipulation,” Vieth says. “Another move from this point would substantively increase the likelihood of a recession sometime in 2020.”

ACT’s odds for a recession over the 18 months have risen from 25% earlier this year to 40%, Vieth adds.

“We’ve been predicting this industrial downturn all year and continue to think it will drag on because the trade war is terrible for US manufacturing,” Denoyer said. “If the consumer can keep the economy out of recession, we think spot truckload rates can turn positive next year as capacity rebalances.”

OEM view

At Navistar’s Investor Day earlier in September, CEO Troy Clarke stated he would not make any comment regarding a recession, but he did say “freight and trucking are going through a transition.”

Navistar predicts a 10% drop in the medium-duty segment and 30% for Classes 6-8 in 2020. And while the rest of 2019 will be rough, Clarke said orders should recover in January 2020.

He also said when GDP is over 2%, which it was for the last two years, there’s a demand for trucks to haul goods. The problem is ACT predicts that to meander around 1.7% for the next two years, so that demand might not be as high as expected

Conversely, if President Trump and President Xi Jinping of China are able to resolve the current trade war, which goes into a 13th round of negotiations sometime after the next Chinese holiday on Oct. 7, the economy should rebound and the trucking industry would reap the benefits.

Market leader Freightliner, owned by Daimler, has responded to the downturn by laying off 900 employees total at two North Carolina plants. These will take effect by Oct. 14.

Fleet perspective

In the airy foyer of Navistar’s headquarters, which hosted the company’s investor dinner, fear-fueled words such as “recession” were smothered by large-scale fleet owners echoing the same positive message of consumer consuming and new orders rolling in.

Max Fuller, executive chairman and co-founder of U.S. Xpress, who claims to have purchased 85,000 trucks in his lifetime, says behind-the-scenes data leads him to believe that following spot rates dropping 35% after record highs, the industry has hit an inflection point and should trend back up, adding the next three months will prove if that is indeed correct. For him, it’s passing the eye test.

“The economy looks like it’s going pretty strong in general,” said Fuller, offering that if it stays that way, it could be “off to the races” for fleet activity.

As a rental provider, Ryder Systems has a different business model, but Tim Fiore, Ryder’s senior vice president and chief procurement officer, shared Fuller’s sentiment.

“Things have slowed a little bit,” Fiori said, but “order rates are still strong.”

“You have to be an excellent gambler to know what’s going to happen,” he added.

As of mid-September, his bet would not be on a big recession, though. He believes there are three signs leading to a prolonged economic contraction. The first is the economy running out of steam, which he doesn’t see happening yet. “I think there is more to go,” he said.

Next is a catastrophic event, something not on the horizon “unless the trade war develops into something that really clamps things down.”

Fiori’s final sign would be the Federal Reserve raising interest rates, which is “clearly going other way.”

“We can weather our way through this,” he said. “I think we just need to get through the next four or five months.”

Pat Gallagher, CEO of PGT Trucking, an open-deck carrier, was downright optimistic.

“We’re seeing the construction business booming,” he said. “I think everywhere you go in major cities you see cranes. I’m bullish on 2020.”

Despite that, Gallagher acknowledged that trucking executives must tighten their belts. His lean strategy is too look at every level from himself to the secretary to cut expenses, take a closer look at maintenance items to prevent downtime, and work with vendors and suppliers to find more efficient ways of doing things.

He seemed open to everything save for cutting driver wages, which went up industrywide in 2018 due to higher demand.

“Driver retention is critical,” he stressed. “When you can’t give people across the board pay increases, you recognize the people that have been with you, so retention bonuses are an important part of what we’re doing.”

Gallagher also mentioned referral and safety bonuses. All told, these can boost a base salary by 10%, he says.

“More importantly we try to be supportive of the family,” he added. “We have a full-time chaplain on staff solely dedicated to our drivers and staff who are experiencing personal or professional problems.”

What Gallagher is really saying is to remember that aside from the confusing macroeconomics, geopolitical quagmires, and fluctuating freight rates, people are the most important asset, and they don’t come with sensors to tell you when they are about to fail. It’s the fleet owner’s role to reach to out.

“Especially in a down market, people become nervous, they become antsy,” he said. “One of our jobs is to reassure them we are going to be here.”

This is a cyclical business after all, and the good times will come again. But if fleets don’t treat their drivers with respect during the bad times, they may not have anyone it it for the long haul during the next boom time.