When Singapore-based Horizon Fuel Cell Technologies Pte Motors began commercializing fuel cells in 2003, the company was “a little bit ambitious, and a little bit early to that party,” noted Craig Knight, CEO and co-founder of spin-off company Hyzon Motors. Now, with Hyzon Motors recently announcing it would combine with a special purpose acquisition company to go public, the time is appears right.

World leaders are clamoring for net-zero emissions in the next 30 years, and there’s a race to find the best technology to achieve that goal. Because of shorter fueling times and longer ranges, hydrogen fuel cells have emerged as the presumptive zero-emission option for long-haul trucking.

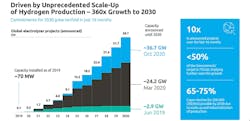

According to the McKinsey Center for Future Mobility, the commercial fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) market will increase 34% annually until 2030, spurred by at least 60 nations targeting zero net emissions by 2050 and the price of hydrogen production coming down as more investment comes in. In 2020, the sector was valued at $1 billion, while in 2030 McKinsey forecasted it will be worth $20 billion, when 10 million FCEVs may be on the road.

Horizon got one of the earliest jumps, having designed and tested newer versions of its proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells over the last two decades. Hyzon medium-duty trucks and buses will employ the company’s Titan fuel cell stack validated by TÜV Rheinland as having “the highest power density on the market.” Due to the top-tier energy density of fuel cells, the Class 8 truck should have a range of around 400 miles per fill up. The electric motor was designed to provide 500kW, the equivalent to 670 horsepower. Along with OTR, the as-of-yet nameless Hyzon heavy duty truck will engage in vocational duty cycles such as refuse and construction.

The latest iterations are being deployed in Asia and Europe in commercial truck and bus applications, with heavy-duty truck testing to begin in California later this year.

All this means the party has officially started and Hyzon is ready for it. Last week Rochester, N.Y.-based Hyzon announced it would go public on the Nasdaq via a business combination with Decarbonization Plus Acquisition Corp, under the ticker HYZN.

“Hyzon is a truly differentiated company that is accelerating and leading the hydrogen transition with captive, proven fuel cell technology and superior performance,” said Erik Anderson, CEO of DCRB, who noted the special purpose acquisition company investigated a dozen other low-carbon platforms.

The deal should close in Q2 and bring $626 million of cash to fund the current phase of operations and growth. By 2023 the company intends to deliver 5,000 fuel cell trucks and buses and scale manufacturing to produce 40,000 annually by 2025. Assembly will occur in the U.S. and Netherlands.

Following that news, Hyzon agreed to build and supply Hiringa Energy in New Zealand with 1,500 HD FCEVs in the next five years. Those 6x4 trucks wit sleeper options will have a Gross Combination Mass (GCM) of 58 metric tonnes (64 US tons) and range of 680km (423 miles).

"This partnership aims to position New Zealand as a global leader in the adoption of zero emission heavy vehicle technology, and we are pleased to be playing a major role in this transition," Knight said. "Deploying 1,500 fuel cell trucks by 2026 is going to make a massive contribution to local decarbonization efforts."

Despite having an active fuel cell business in Asia and Europe, with parent Horizon providing 27 megawatts of fuel cells in 2019, the company is relatively unknown in North America. FleetOwner recently spoke with Knight to catch up on Hyzon’s recent flurry of activity and what the future holds.

FleetOwner: How did all this start?

Craig Knight: We were on that first wave of the commercial vehicle development in China, where most of Horizon’s development engineers and manufacturing are, and learned that the rest of the world was somewhat behind in terms of driving electrification of commercial vehicles. When we went out to globalize our capability, the original concept was to become essentially an “Intel Inside” for the fuel cell powertrains within the commercial vehicles. But the broader world wasn't ready for that, so we instead started talking to the other parties trying to accelerate the electric motor and hydrogen storage, as it goes with all the DC power systems and batteries.

FO: What does Hyzon bring to the party?

CG: Truck brands are mostly putting an engine in and the other stuff is provided by suppliers, and that fuel cell truck supply chain is actually very different. Hyzon can be the master integrator and provide branded trucks — making the engine and the fuel cell engine and outsourcing non-core components, such as brakes, chassis, and wheels. These are important, but they're not necessarily where a lot of value is created in the vehicle. The value tends to be created in the vehicle through the engine system and then somewhat through some of the software controls and safety.

We've come at this from the core technology, the base technology. We weren’t a truck company, but we've been hiring all the key resources with trucking background experience in axle building and chassis design to be able to assemble these capabilities. In Europe, DAF is a major partner for the chassis systems.

In the U.S., Fontaine Modification, as an example, would put the physical boxes together after we design the systems. They have the capacity to build thousands of trucks, so we have that fungible capacity at our disposal without going and investing in multibillion-dollar plants.

But our 17-year journey in fuel cell technology gives us a very solid base. And all the industry benchmarking done put the Hyzon Motors fuel cell capability at the top of the charts in terms of performance and power density, which is very important in heavy vehicles.

We can use one fuel cell module to power a Class 8 truck and go on the highway. So far, other fuel cell companies haven't been able to do that; they usually put two or three fuel cells for a heavier truck.

FO: Can you talk about the 2021 rollouts?

CG: The new European factory has started operations, and deliveries start this quarter, which is probably about two months behind plan, which is primarily a function of the incredible disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. North American deployments will start in the second half of 2021.

California is the starting point, because it hangs onto the European coattails. That can create a second wave if some of the California initiatives can be adopted by other states. We’ve already seen New Jersey and a couple other states start to pick up the goals and deadlines of selling zero-emission vehicles. If we can start to see some of the state and federal policy stuff start to emulate California, that would be great.

FO: Concerning the merger, what does the influx of approximately $626 million allow Hyzon to do in terms of scaling truck production and infrastructure, and how does it directly impact the North American plans?

CG: Hyzon will continue investing in R&D to maintain and extend our competitive advantages in the core fuel cell and vehicle system technologies.

Hyzon will also build out fuel cell and integrated system production in the U.S., as well as advanced material development and vehicle engineering capabilities. More news will be coming in the next month or two on some of those initiatives.

Unfortunately, the current state of play on the U.S. facilities and activities has us almost a full year behind the activities in Europe, but we are going to have a small number of demo vehicles deployed in the U.S. before the end of 2021.

FO: How long has the deal been in the works, and were you encouraged by other zero-emission truck makers that went public last year, such as Hyliion and Nikola, or was this always part of the plan?

CG: Hyzon always knew we needed to have a strong balance sheet to compete in this space, and, in fact, seeking substantial investment for the zero-emission heavy vehicle application was the entire reason for the inception of Hyzon Motors, and the reason the parent company was willing to sell down its ownership position significantly to prepare the company for these challenges.

We entertained a few options for fortifying our balance sheet, but when the DCRB SPAC came along, the fit was simply hand in glove, and too good to pass up.

FO: Is Horizon still the parent company now, or is Hyzon/DCRB its own thing now?

CG: The Hyzon entity will be independently managed through a Board of Directors with several new independent directors taking their place, mandated to decide on the company’s future direction, including Erik Anderson, the DCRB CEO, who has vast experience with growing companies as they enter public life. Horizon will retain a meaningful stake in the business, but it is the Hyzon board that will be calling the shots on strategic decisions.

FO: You have previously stated hydrogen infrastructure could be ready in 5 to 7 years. How can this happen?

CG: In the U.S., fueling infrastructure is being built for light vehicles, which is not very convenient. It's often not suitable for the heavy vehicles, so we're only just starting to get through some of the practicalities of that. However, what we're seeing is with our focus on back-to-base vehicle operations, we can justify infrastructure buildout quite easily. And we have willing partners, who will be the filling stations right next to a depot that's going to have 200 trucks.

The great thing about doing commercial fleet operations is the utilization. You can anticipate the mileage a week or month in advance and what you need to build to match capacity with offtake. It's much easier compared to if you're building stations, waiting for people to travel along interstates and stop and fill up. This infrastructure can be a very good investment, it can get a return on the investment right from day one because you plan the infrastructure spend for the for the anticipated utilization.

FO: How do you envision the hydrogen will be produced?

CG: You can’t argue with the localizing force of hydrogen. It's a very challenging thing to move around and the economics of moving it are not attractive. You have to have a flexible and open-minded hydrogen strategy because supplying the most cost effective hydrogen in Houston is going to be very different to supplying the most cost effective hydrogen in Alberta or New Jersey. It could be hydro power in some places, and geothermal or wind in others. Only once you get to a little bit of scale with all these techniques and competing technologies will it become really clear what the advantaged approaches are in the different regions.

We're starting to cherry pick from some of these technology partners, and sign agreements selectively here and there to have different processes that are suitable in different areas based on available local resources, available infrastructure, and cost of electricity.

There will be many more holistic solutions that pop up, a lot of waste-based technologies will continue to evolve and improve, such as reforming landfill gases and other unwanted materials into hydrogen. That waste-based production of hydrogen is very attractive because wherever there are humans and animals, there's some form of a waste.

You can capture most of the carbon from that process, so you can have a beautiful carbon-negative conversion process and get the hydrogen out, instead of letting it become methane with a very big impact on the ozone layer.

FO: How could the U.S. federal government help spur a hydrogen-based transportation ecosystem?

CG: The way we look at government support is, “Just help us get to scale; you don't need to pave the way in gold, you don't need to drape us in a whole bunch of grants to get us there, but we do need some help.”

That’s because it's very hard for a very tiny nascent industry to compete with a very well-established big industry with an almost an infinite footprint. The switch is only thrown, though, when you actually hit really meaningful cost structure positions, when zero-emission fleet operations reach parity with diesel.

It's our belief that our technology and the work we're doing will enable us to provide trucking operations at and below diesel fleet economics within the next two to three years in many jurisdictions.