As the economy recovers from the COVID recession, freight is booming, and the threat of the virus might be receding across the U.S. But as commodity prices rise and availability wanes as the supply chain continues to be strained, inflation could hamper the industry.

The trucking and transportation business is good right now, “but there might be a cloud or two on the horizon,” said Jim Meil, principal industry analyst with ACT Research. Economic “forecasting is a lot about supply—not as usual about demand—because the customer demand is there. The question is whether we can push the product through the supply chain.”

Meil, who spoke during a Sept. 21 ACT Research webinar review of the transportation and commercial vehicle industries, said the transportation economy is showing signs of strength, leading to “the downside of good,” which is supply chain struggles and inflation.

Some of the “bad news” Meil cited: Commodity prices continue to rise in 2021. “Oil is $70 a barrel—recall that in the second half of last year, it was at $40 a barrel,” he noted. “Maybe that’s inflationary?”

Semiconductor microchips, steel, aluminum, natural gas, and “the list goes on of commodity prices that are on the rise,” Meil said. That’s putting inflation front and center for the transportation industry, and it is “a Main Street worry, but maybe it's not on the Wall Street radar. Maybe it's a Fed concern, but a Fed concern in 2022.”

North America’s commercial vehicle industry is experiencing material capacity constraints that are dictating production across the continent, according to ACT Research’s Transportation Digest.

“Panic is not much of an overstatement for everyone involved in the motor vehicle supply chain these days,” said Kenny Vieth, ACT president and senior analyst. “From early-stage fabrication of components to the buyers of new trucks, the universal sentiment is ‘it’s just crazy out there.’ For heavy trucks, no less than for medium and light vehicles, procuring supplies to manufacture products has become the top management priority.”

Are commodities causing inflation?

The microchip shortage across the globe has hampered the production of everything from new trucks and cars to consumer electronics such as smartphones and computers. Microprocessor prices are expected to rise 4% this year, according to IC Insights, a semiconductor market research company.

“That’s not a lot, but keep in mind that microprocessors ordinarily decline in price,” Meile said. “That’s been one of the factors behind deflation in consumer electronics, personal computers, and other technology. So if they are going up 4%, that’s an inflation contributor.”

The chip shortages, Meil said, will last until next year and could extend into 2023 “if we’re to believe the pronouncements of some industry-leading figures in both the technology area and in the motor vehicle area."

Another essential commodity to the trucking industry is steel, which is seeing prices three times higher than at the start of the year. “There is some sniff of perhaps hitting a peak,” Meil said. “Iron ore prices have fallen over the last few weeks.” He added that hot roll band (HRB) prices fell 5% to 10% in mid-September. On Sept. 13, HRB was going for $2,078 per metric ton. “But we have to recognize that it’s a long way to go down before we return to prices of about $650 per metric ton—the way we started the year.”

The commodities problems and other trends that look to continue into 2022 are putting “inflation front and center as a business concern,” Meil said.

According to the Institute for Supply Management’s Report on Business, supplier deliveries are “just about at the low end,” Mei explained. “That is to say slow performance, slow delivery.”

He added that purchasing managers that are reporting this slow performance also note that their customers’ inventories are “about as thin as it gets,” Meil said. “Stretched supply chains, erratic supply chains are contributing to inflation.”

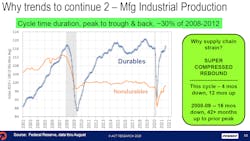

The story behind the supply chain challenges is the compressed, two-month COVID recession, compared to the prolonged 16-month Great Recession of 2008 to 2009. “It was a long time falling into the pits and reaching the low point,” Meil said. “And it took three and a half to four years to recover back and makeup all the lost ground. This year, the timeframes have been compressed—and that is really the story behind the supply chain challenges that we’ve got right now.”

In North America, heavy-truck production has seen sizable gaps between build plans and actual production—especially in June and July, and “prospectively in the months ahead,” Vieth said. “And if the factory can’t build, then the dealers can’t sell.”

Noting that ACT has rolled back heavy-duty truck forecasts in the past, Vieth pointed out, “that was when the economy weakened and freight declined. The supply-chain crisis has created a unique situation, a major forecast haircut in a period of ripping demand. The sizeable forecast reductions of the past two months are unprecedented—especially considering that 2021 is more than half in the books.”

During this period of a recovering economy, government stimulus, strong freight, record freight rates, rising vehicle backlogs, and falling inventories, “the usual bearings and landmarks we use to guide a forecast don’t work,” Veith said. “At least for 2021 and certainly into early 2022, the forecast is determined by supply considerations, rather than by what demand dictates.”

Good news

On the other side, there is a lot of good news for the industry, Meil said. “The referees on the business cycle have told us that the 2020 COVID recession was just a two-month wonder,” he said. “And the recovery has been strong after those two months.”

Those two months of the COVID recession were in April and May 2020, according to Markit Economics’ monthly Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). That index, Meil said, shows “the transition that occurred in the summer of 2020 as we moved from COVID desperation to righting the ship. Then, since the spring of 2021, strong numbers from the purchasing managers and I think representative of the global economy.”

The North American numbers in the PMI are “about the strongest in the 25-year history of this survey,” Meil noted. Europe also sees high marks while the “rest of the world is a little bit more of a mixed story—but a picture that is of fundamental global health in the economy.”

While August’s U.S. jobs report was “a bit of a disappointment,” Meil said to “give it a month or two” as the economy is still feeling the effects of the past COVID stimulus packages, noting there could be more in the works as the Biden administration tries to get more spending through Congress this fall.

The COVID front is also producing some good news for the economy, Meil said. He cited the recent moves by the FDA to declare that most people won’t need a vaccine booster shot unless they are 65 and older or among the more vulnerable. The FDA also approved the Pfizer vaccine for children as young as 5 years old.

The recent delta variant surge of COVID in July and August was the fourth wave of the virus in the U.S. over the past 18 months. “But we seem to have had a fade,” Meil said of the COVID cases in the U.S. “We have some precedent in countries like India that had a rapid run-up [of delta], and then it came down. So, fingers crossed, maybe the slide down has begun. We’ll see the story on that over the next few weeks and months.”

Adding to the good news: “Asset and commodity prices remain high and trucking indicators are great,” Meil said.

He said to watch the Biden administration, which had “a tough August and early September,” this fall as it looks for a win on infrastructure and other spending plans.

About the Author

Josh Fisher

Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief Josh Fisher has been with FleetOwner since 2017. He covers everything from modern fleet management to operational efficiency, artificial intelligence, autonomous trucking, alternative fuels and powertrains, regulations, and emerging transportation technology. Based in Maryland, he writes the Lane Shift Ahead column about the changing North American transportation landscape.