(Bloomberg) — General Motors Co. executives had laid the groundwork for a new labor agreement with the United Auto Workers union in September 2015. The company had met most of the union’s demands with a proposal that would have boosted pay and benefits by almost $1 billion over four years.

If the UAW’s then-President Dennis Williams had agreed and the deal been ratified, it would have set a precedent for similar accords between the UAW and Ford Motor Co. and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV. But instead, Williams balked and went to Fiat Chrysler to cut a pattern-setting deal that pushed GM’s four-year labor costs up by $1.9 billion.

The roughly $1 billion difference seemed like hard luck at the time, but suspicions arose at GM headquarters when Al Iacobelli, Fiat Chrysler’s former labor relations chief who later joined GM, was indicted in July 2017, according to people familiar with the matter. Federal investigators charged him for tapping into a union training-center fund for years to buy himself a Ferrari and Montblanc pens, and to lavish union officers with $1.5 million in cash and gifts. GM attorneys began to suspect Williams and other union leaders may have been swayed by graft to favor Fiat Chrysler at their expense, a charge current UAW leaders deny and that the Justice Department hasn’t made.

The Iacobelli case set off a more than two-year effort by GM’s legal staff to establish a pattern of coziness between the UAW and Fiat Chrysler, leading to an unprecedented step: hitting its rival with a federal racketeering lawsuit. Bloomberg spoke with several people involved in the lawsuit and pored over court filings to assemble this detailed account of the evidence GM’s lawyers pieced together to convince Chief Executive Officer Mary Barra they had a strong case of unfair behavior by Fiat Chrysler and the union.

When Iacobelli pleaded guilty to violating labor laws, alarm bells went off in GM General Counsel Craig Glidden’s office. He and his attorneys became increasingly convinced Fiat Chrysler had bought off union officers as part of a strategy to gain a cost advantage. They also started doing forensic work to match up emails and key dates in the Fiat Chrysler-UAW scandal with overtures the company’s late Chief Executive Officer, Sergio Marchionne, made to pressure Barra into a merger she didn’t want.

Barra, 57, relied on her staff to sift through court filings and build a bribery case, even though she knew it would be incendiary. GM’s top managers didn’t make a final decision until days before filing the suit on Nov. 20. For Barra, the choice to move ahead rested on two key points. First, cheating to get a better labor deal offended her personal sense of fair competition. The second rationale was more pragmatic: If GM was injured financially, someone had to hold Fiat Chrysler accountable.

“I would just say, it was not a decision that we made lightly,” Barra said during an investor conference last month. “It was something that we very, very carefully considered.”

Fiat Chrysler and its chairman, John Elkann, have denied the allegations. The company and UAW have said the nine former leaders who worked on past labor contracts and have been convicted of corruption acted on their own. Both have also noted that workers rejected the initial agreement Fiat Chrysler and the union reached in 2015, arguing that workers had the final say and GM wasn’t damaged.

Cindy Estrada, the UAW’s chief negotiator with GM in 2015, recalls events differently than how the company recounts in its suit. She said in an interview that the UAW walked on GM’s offer because management insisted on cutting profit sharing, which the union would not accept. Williams went with Fiat Chrysler’s offer because GM fell short on a key bargaining issue, she said in a phone interview.

‘Rogue Individuals’

When Iacobelli, the highest-ranking former Fiat Chrysler executive to plead guilty, was sentenced to 5.5 years in prison, Fiat Chrysler said it was a victim of illegal conduct by “rogue individuals,” and the UAW denied that labor contracts were affected by the scheme.

But that claim may not carry much weight with the court in GM’s civil case, said James Jacobs, a New York University law professor. “Under federal law, the corporation is responsible for the conduct of its agents, so the rogue argument won’t fly,” he said by email.

GM points to Justice Department documents in which federal prosecutors say Fiat Chrysler made illegal payments to union officials in order to “obtain benefits, concessions and advantages.” The government stated in court filings that Iacobelli and his co-conspirators wanted to keep UAW leaders “fat, dumb and happy.”

Iacobelli, who is serving his sentence at a federal prison in West Virginia, did not reply to a request for comment. GM hired him in January 2016, six months after he left Fiat Chrysler, and fired him the following year.

In a Dec. 4 interview, U.S. Attorney Matthew Schneider, who is heading the Justice Department’s investigation, stopped short of saying UAW corruption has compromised labor contracts, as GM has alleged. “At this stage, I’m not able to draw that conclusion right now,” he said. “That’s why we’re continuing to look at it.” Schneider also said the government’s case is proceeding on a separate track unrelated to GM’s legal action.

GM alleges Fiat Chrysler’s racket dates back to at least 2009, when Iacobelli and Fiat Chrysler financial analyst Jerome Durden set up a scheme to funnel money from union training funds to UAW leaders. Durden later pleaded guilty to failure to file tax returns and fraud and was sentenced to 15 months in prison.

Two tiers

A big part of GM’s damage claim revolves around a tiered wage system the UAW allowed Detroit automakers to set up in 2007 when the companies were teetering. The union let them hire new employees at half the prevailing hourly wage rate for senior workers and to give them less-generous benefits. GM and Chrysler agreed to limit these new hires, known as tier-two workers, to 25% of their ranks until 2009, the year both ended up in bankruptcy.

The cap on tier-two workers was removed entirely that year to help the companies, but only on the condition limits would be back in place by 2015. GM said in its lawsuit that tier-two workers made up 20% of its unionized workforce that year. The company alleges the UAW gave Fiat Chrysler special permission — via an undisclosed side letter — to ignore the reinstated cap, an arrangement GM believes was sealed with bribes. At Fiat Chrysler, tier-two workers accounted for 42% of its 2015 workforce.

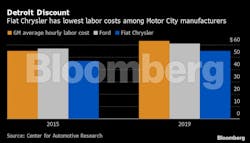

GM alleges Fiat Chrysler also got the UAW’s go-ahead to hire far more lower-paid temporary workers. This year, Fiat Chrysler’s hourly labor costs are about $55, compared with GM’s $63.

“Looks to me like GM has a strong case,” Jacobs said. “The bribery put it a competitive disadvantage.”

Marchionne’s ‘Wingman’

GM claims that Marchionne, who died last year, was complicit in bribing union leaders to help coax GM into a merger. In June 2015, when GM, Ford and Fiat Chrysler were all in preliminary discussions for new four-year labor deals, the UAW’s then-president Williams and Estrada met privately with Barra, then-GM President Dan Ammann and other executives.

The UAW leaders told GM executives they would support a merger, removing a key potential stumbling block, according to the company’s lawsuit. This was unusual — unions typically oppose mergers because cost savings tend to be borne out of plant closings and job cuts.

To GM, it was proof Fiat Chrysler’s CEO had convinced UAW officials to do his bidding, something it later concluded must have resulted from bribes. The company refers to Williams in its lawsuit as Marchionne’s “wingman.” To date, neither he nor Estrada have been charged with wrongdoing by federal prosecutors investigating corruption at the union.

Representatives for Williams, who retired from the UAW in June 2018, could not be reached for comment.

Different recollection

Estrada said she and Williams did not support the merger. She said she told Barra she feared overlap in products and plants would reduce jobs and union membership. She said Williams had the same concerns and that neither of them openly supported a deal.

“I wasn’t in a meeting with Dennis saying, saying ‘merger, merger, merger,’” Estrada said. “I would have remembered that. I never recall Dennis saying that. I recall it being the opposite.”

In addition to sticking to its claim, the 2015 agreement was not marred by the corrupt executives who clinched it, Fiat Chrysler could argue that labor contracts carmakers reach with the union are distinct enough that one company cannot blame another for concessions. This year, for example, GM agreed to pay workers bigger ratification bonuses than Ford or Fiat Chrysler. The UAW also relented — after a 40-day strike — in allowing the company to close three plants.

“The pattern is never cookie-cutter for all three companies, but they are often very close,” said Kristin Dziczek, vice president of the labor and economics group at the Center for Automotive Research. “The difference is often what is actually enforced by the union.”