(Bloomberg) – Amit Sekhri took up trucking in the thick of the Great Recession, drawn in part by the freedom of driving the open roads. He was prepared for long hours and weeks away from home. But two of his biggest—and least expected—gripes were the constant phone calls and late payments. Like many truckers, Sekhri booked his jobs through freight brokers, a class of intermediaries who do most of their business by phone. And many have a bad habit of paying late.

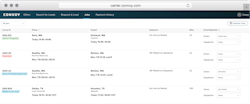

Then he discovered an app called Convoy. It lets him select nearby loads listed by shippers and get paid a day or two after completing a trip. It uses a phone’s GPS to estimate a driver’s arrival time for pickup and tracks where he is throughout the route. For these reasons, Convoy Inc. is often described as “Uber for trucking”—a moniker that took hold before the real Uber set up a competing business and was gripped by a corporate crisis.

Sekhri, 30, now drives his own truck and serves as a dispatcher for four drivers who deliver orders through Convoy, traditional job boards and occasionally Uber Freight. He credits Convoy with solving some of his main grievances with the job. “It’s pretty easy. You like the price, you accept it, you assign it to a driver, and you can track them. I don’t have to call the driver and say, ‘Where you at?’” Sekhri says. Convoy also lists accurate pickup times, letting him squeeze in a shower or meal outside his truck.

But Sekhri has a bigger problem: Job rates are declining fast. App reviews for Convoy are riddled with complaints from drivers about low prices. Sekhri and two other Convoy drivers who spoke to Bloomberg echoed those concerns. One of them shut down his business in March. Sekhri says he uses Convoy for 10% to 15% of his loads—only when prices meet his needs. “I’ve got four kids to support,” he says. “I’m still hanging in and hoping it will get better.”

This isn’t unique to Convoy. Rates are falling across North America after two years of increases. Spot demand, which excludes long-term freight contracts, plummeted 27% through Oct. 25, and most drivers aren’t expecting business to improve over the next six months, according to market research from Bloomberg and Truckstop.com. Those who bought flatbeds during the surge are now struggling to find work and make auto payments.

For Convoy, the company risks drawing comparisons to Uber in less flattering ways: drivers grousing about getting squeezed and a business model that has yet to turn a profit. One possible remedy is a dramatic expansion of its bidding system that Convoy plans to announce Tuesday. It would create a sort of EBay for freight, where drivers can submit offers for a vast number of jobs listed by shippers. Convoy says this will allow drivers to find more work and reduce trips without a load, but the theory isn’t proven. It could just as easily drive down prices and exacerbate the pay problem.

Dan Lewis, the chief executive officer, says he’s sympathetic to concerns from drivers, especially small trucking companies that are often hit the hardest. He says he can’t control the market, but Convoy can help make it more efficient for drivers. “They’re just thinking in their head, ‘Hey, I did this job last year, and I got $1,000. Now I’m getting paid $900. Why am I being paid less?’” Lewis says. “What we want to do is help them reduce their costs."

Lewis doesn’t exactly fit in at a truck stop. The 38-year-old is a graduate of Yale University and worked at Microsoft Corp., Google and Amazon.com Inc. Before starting Convoy in 2015, he hung out at service stations along Interstate 5 for research. He says he talked at length with drivers, learned the lingo and listened to what frustrates them. Lewis realized technology could solve some of the trucking business’s arcana.

The industry didn’t get it initially, Lewis says. Technology doesn’t usually elicit happy thoughts for truck drivers, amid talk of autonomous vehicles displacing their jobs. “Tech doesn’t move freight,” Lewis would often hear. “People move freight.”

But rich people got it, taken with the potential to remake a $141 billion market for the better. The company has raised about $275 million in venture capital from a roster of investors that reads like a guest list at Davos. Among them are Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Marc Benioff. Dara Khosrowshahi invested personally before becoming CEO of Uber Technologies Inc. (He has since sold his stake.)

The trucking market was accelerating in tandem with Convoy and Uber Freight. By the end of last year, Convoy was generating about $300 million in revenue on an annualized basis, and Uber Freight was on track for $500 million, estimates Silpa Paul, analyst for research firm Frost & Sullivan. The tech companies’ growth has come at the expense of smaller, traditional brokers, says Lee Klaskow, analyst, Bloomberg Intelligence. “You have these old-school guys smoking a cigarette with a Rolodex and a phone,” he says, though some are finally waking up to the need to modernize.

Travis Washington, a trucker based outside Atlanta, says he once called to arrange a job with J.B. Hunt Transport Services Inc. and was told to hang up and book through the company’s app. The broker gave him an extra $10 for doing so. But he still uses Convoy’s app daily, including a service called Convoy Go. It lets drivers bring only the cab of their truck and hook up to a trailer pre-filled with cargo at pickup. It can also save on fuel and other costs associated with a trailer. But Washington says Convoy’s prices for the return trip are typically too low, and so he loads the Convoy trailer with freight booked through a traditional broker. It’s not a great outcome for Convoy, but the company doesn’t discourage the practice, as long as the trailer is returned within a few days.

This year, more drivers are having to find creative ways to cut costs. The startup that wants to be the new face of the trucking business has suddenly become for some drivers a symbol of a pricing crunch. Lewis recalls a difficult series of conversations in March at the Mid-America Trucking Show in Kentucky with drivers concerned about pricing. Lewis says Convoy is trying to show drivers how it can help, even when prices are low.

It wasn’t enough to keep Ira Lawrence in business. He bought a truck in 2017 and signed up to drive for Convoy after taking a retirement package from the Canadian Navy. He and his wife in Oak Harbor, Washington, discovered that making a living wage was a lot harder than they expected, even during the boom. Weekly fuel costs were $2,400 to $3,000. Insurance was more than $1,600 a month. They managed to pay off the truck and trailer, but monthly maintenance costs exceeded $1,500. “The overall cost of owning a truck is through the roof,” Lawrence says. “We thought it would be this glorified life of: Get a load; stay there for a few days; and then get a load to somewhere else.”

Four out of five jobs for Lawrence came through Convoy. The ability to get paid within 48 hours of completing a trip helped them stay afloat for a few years. He was forced to shut down his trucking business in March, when he was unable to cover insurance costs. These days, Lawrence gets paid to train other drivers. He warns them about the risks, he says. But he still recommends the Convoy app and frequently dons his Convoy T-shirt, sweater and trucker hat.

There are three types of people Lewis needs to please with Convoy: drivers, who want to get paid more; shippers, who want to pay less; and investors, who want to get paid the most. No one is completely satisfied right now, but Convoy says technology can solve everybody’s needs by wringing inefficiencies out of the market.

Part of the original mission was to eliminate long return drives without a load. An automated service the company introduced three months ago bundles multiple loads and is now available for the majority of trips in Atlanta and Los Angeles. The app has since added other data to improve transactions and waste less driver time, including grading shippers based on how quickly they load a shipment. Companies with slow loading docks pay a premium because fewer drivers want the job, Lewis says.

As for someday turning a profit, Lewis says the business is “built to reach better-than-industry economics on each market we enter.” Working in Convoy’s favor, he says, is that freight brokerage has a long tradition of generating profits.

The goal for Convoy, in other words, is to out-Uber the larger, more established trucking companies—as well as Uber itself. Last month, Uber said it would spend $2 billion to expand freight operations in Chicago.

Convoy’s newly expanded auction system, called Direct to Shipper, is part of that strategy. In the past, Convoy showed drivers a limited number of jobs, only the ones the company thinks it could fulfill. With the new service, Convoy will list every single load and allow drivers to bid on each one. If it works as intended, drivers should be able to line up more jobs on routes they want and at rates they like, meaning less empty time and more money, says Ziad Ismail, the chief product officer at Convoy. It’s more eBay than Uber and could increase options for drivers by a factor of 10, he says.

In a less optimistic scenario, pitting drivers against one another to offer the lowest rate could end up further depressing prices. Echoing a mantra in Silicon Valley, Ismail suggests truckers could make up for an earnings shortfall in volume. “Drivers are trying to fill up their schedule,” he says. “If we can 10X the number of shipments they have available to them, the likelihood they can find a shipment that is closer to them or has less waiting time increases exponentially.”

For shippers, especially smaller ones, Convoy has saved them a lot of money, while giving them the sort of attention other companies can’t afford to provide. Waiakea Springs, a Hawaiian maker of bottled water, uses Convoy for three-quarters of its shipments, from 10% almost two years ago. Convoy assigned the company a dedicated account representative to find the best prices and ensure smooth service, something Uber Freight wouldn’t do for such a small customer, says Alexandra Alegria, the director of supply chain and logistics for Waiakea Springs. Convoy also agreed to help the water company achieve an environmental goal of switching to all-electric vehicles starting next year, by connecting them with green trucking companies.

Waiakea Springs sends as many as 10 trucks a week from California to Pennsylvania and New Jersey, mainly to the convenience store chain Wawa. That used to cost as much as $8,000, but the price on Convoy usually tops out at $5,300, Alegria says. But a few times, low-ball offers attracted poor drivers, she says. Convoy solved the issue in a very low-tech way. She called her account rep, who lined up a trucking company with a large fleet that’s now dedicated to shipping all of Waiakea Springs’ orders. “The majority of other brokers I’ve worked with send you to one of their giant call centers,” Alegria says. “We haven’t had anyone who has been as invested in our growth as Convoy has.”