Even with inflation at an all-time high, industry analysts at FTR Transportation Intelligence aren’t overly concerned about a recession.

The inflation rate in the U.S. hit 9.1% in June, up from 8.6% in May and above market forecasts of 8.8%. The freight market, however, has seen inflationary pressure for two years now, explained Eric Starks, FTR’s CEO and chairman, during FTR’s July 14 State of Freight webinar.

“We have been seeing the spot markets going crazy, and that’s why we’ve seen drivers coming back in as leased owner-operators,” Starks explained. “Clearly, fuel is a big part of inflationary pressure for transportation, but the shipper is really the one bearing a lot of that cost. The carrier eats the cost at first but then they pass it on. There are potentially some cashflow issues, but we are not seeing a significant problem there yet.”

Though not necessarily a surprise, Starks emphasized that inflation is indeed “way too high” and that there is a need to slow down the rate of growth.

“And that’s what the Fed is doing,” he said. “They have gone through and have been raising interest rates to try to bring this down. One of the things we have a concern about is what happens if they over-tighten? I’m not overly concerned structurally with that, but that is something we have to pay significant attention to.”

Most of this inflationary pressure, Starks added, is global in nature and has really nothing to do with what is happening domestically. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, for example, is causing pricing pressure for fuel, he noted.

See also: Diesel shatters all-time per-gallon price record

In addition, over the last two years, inventories were already too low for the consumer market, and the problem was exacerbated when China shut down for an extended period due to COVID-19 outbreaks, cutting off inventory movement into the U.S. Since Shanghai has begun easing COVID lockdown restrictions, economists anticipate a surge in inventory coming in from China over the next several months, which could further exacerbate port and supply chain challenges.

“As we try to understand what that inventory market does to how freight flows, the best way is to look at port activity and import and export numbers,” Starks explained. “As of 2019, things were relatively normal; we had an understanding of how much was coming in versus what was going out. Since then, that has radically changed. We have seen a surge on the import side, and we have seen a decline on the export market.”

“That creates problems at our ports, and it creates issues on how the supply chain works,” he added. “It creates some additional imbalance.”

Starks also pointed to a shift in demand from the consumer market into manufacturing.

The industrial sector accounts for a lot of freight activity, explained Avery Vise, FTR’s VP of trucking. “A recession is not welcome, but if a recession kills inflation, it might not be the worst thing in the world,” he said.

AB5 and the shifting freight market

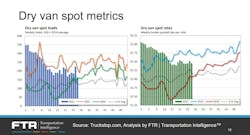

Dry van spot volumes, according to Truckstop.com data, started the year at close to record levels and then declined steadily before beginning to stabilize in April. There has been a similar dynamic in dry van spot rates, though it was much more gradual, Vise pointed out.

Dry van spot metrics are also running below comparable 2021 levels both in volume and rates.“On a seasonally adjusted basis, we see that volume has fallen quite sharply this year from a record level heading into the year,” Vise explained. “But we also see spot volume is still running way ahead of where it was prior to the pandemic.”

Further, total broker-posted dry van rates are about 63 cents below the record posted last year. And with the increase in diesel prices over the last four months, dry van rates are nearly $1 below the level they were last year.

“We are seeing in the market there is not a weakening of freight demand, but rather a shift in activity from spot—which had taken a larger share of capacity in 2021—back toward the route-guided environment,” Vise said.

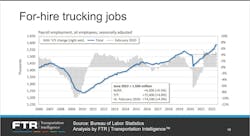

As of June, for-hire trucking employment reached an all-time high and is more than 74,000 jobs ahead of February 2020. Trucking employment has seen a nearly 5% increase compared to pre-pandemic levels, whereas the entire U.S. economy still has not quite returned to pre-pandemic levels, Vise said.That growth was especially strong in the second quarter, with the combined gain of more than 31,000 jobs in April and May—marking the second strongest two-month increase on record.

“There is clearly plenty of demand for drivers. If there weren’t, we wouldn’t be seeing that much hiring taking place,” Vise said. “There seems to be ample availability of drivers. Together these points reinforce what the [Truckstop.com] data was telling us. Yes, we are having a cooling spot market, but so far that is resulting mostly from a shift in activity from spot rate to contract from a sharp drop in overall freight demand.”

So, where did all these drivers come from? The short answer is they have been there all along, Vise said. They have just been in a different part of the market.

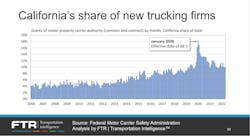

The surge in newly authorized carriers that began in the middle of 2020 has eased recently as rates have cooled and diesel prices have surged. The number of net revocations of authority has been rising since late last year and set a record in June.

“Most of these operations—more than 70%, in fact—are single-truck trucking companies,” Vise explained. “Most have worked for larger companies prior to the pandemic either as company drivers or as leased owner-operators. There has been a capacity shift resulting from drivers who worked directly for larger carriers and now are working for intermediaries as independent carriers.”

And now that the leased owner-operator model in the state of California is outlawed under Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), it opens up additional capacity opportunities for carriers. The question, Vise pointed out, becomes how will carriers comply?The most direct way—and the way California wants them to comply—is to convert those leased owner-operators into employee drivers. The carrier can provide a truck, or they can adopt a two-check system whereby the trucking company pays the former owner-operator as an employee, takes out payroll taxes, and offers benefits, Vise explained. Then, there is a separate lease payment made to the former truck owner to use the truck.

See also: With California law, trucking operations face uncertainty

Another approach would be to move from a leased owner-operator model to a brokerage model, whereby truckload carriers use their logistics units to retain individual carriers on a load-by-load basis.

“We’ve already seen that shift at some carriers in recent years,” Vise said, noting many began adopting that approach in late 2019 and January 2020, which was when the trucking industry thought it was going to have to comply with AB5 until the courts intervened.

“As we look at data both in employment and new carriers over the next few months, we may see some skewing of both of those upward as we see an increase in the number of employees in California and perhaps the increase in the number of carriers,” Vise added. “We will be looking closely as to what degree this AB5 issue is going to skew employment and new carrier figures moving forward.”