Reverse Logistics: A problem that fleets can help solve

The holiday shopping season is in full swing, with Christmas just 19 days away. All that shopping also means that retailers will deal with returned merchandise.

Last year, 13% of overall holiday shopping purchases were returned in November and December, and 16% of all December orders were returned, according to Salesforce data. This year, Salesforce predicts even more holiday returns in addition to regular returns.

This is part one of a two-part story on the reverse logistics problem facing 3PLs and their fleet partners. Read part two here.

These returns—that many retailers and businesses have allowed to pile up since the pandemic—have left the industry scrambling to get a grip on their returns process.

See also: Three Ps can help your truck fleet deliver on time this holiday season

"You get to this point where all these returns are coming back, and the logistics around getting them back to the store where they can possibly be resold is a huge challenge that is still just in its infancy in terms of getting fixed," Mark Delaney, VP of retail industry strategy at Fourkites, told FleetOwner.

For-hire fleets and owner-operators could find opportunities to alleviate some of the retail pain points associated with returns and reverse logistics by picking up a few extra lanes hauling returned goods back to their source.

"Anytime you have a problem that hasn't been figured out yet, to me, that's an opportunity for collaboration, for cooperation, for more strategic conversation," Delaney said of fleets that want to partner with these retail companies.

A problem that fleets can help solve

Consumer returns and reverse logistics have become a nationwide challenge for retailers and businesses. U.S. consumers returned $816 billion of goods in 2022 alone, fueled largely by e-commerce purchases. The Atlantic reported that the return rate for online purchases is 15% to 30%, compared to a single-digit return rate for brick-and-mortar purchases.

Overall, 2022’s returns resulted in 9.5 billion lb. of goods—many in new condition—dumped in landfills, according to the Optoro 2022 Impact Report. Not only are returns a problem for the environment, but retailers not sending goods to landfills are running out of warehouse space for returns awaiting processing.

With the sharp increase in e-commerce since the pandemic and no signs of slowing along with the continuing complexities of returns, transportation partners must find ways to simplify reverse logistics.

The role logistics providers play

Reverse logistics doesn’t only affect the business selling the goods. It also affects the trucking fleets delivering the goods.

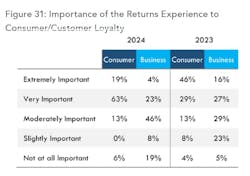

According to the 2024 Annual Third-Party Logistics Study, 82% of consumer-focused brands ranked the return process as important for customer loyalty, up 75% from the previous year. But only 27% of business-exclusive shippers agreed. “The continued and increased divide continues to indicate that business-exclusive shippers still need to buy into the connection between the returns experience and loyalty,” report authors wrote.

See also: How 3PLs, shippers are combating challenges with technology

More than 70% of consumer-focused companies expect returns to increase, according to the study that polled both consumer and business-exclusive shippers, creating even more of a challenge in the future if current reverse logistics challenges aren’t addressed.

The survey found that 44% of consumer-focused shippers identified their reverse logistics capabilities as strong, and only 24% of business-focused shippers said theirs were. This has led shippers to outsource their reverse logistics, which more than half of shippers from both consumer-focused and business-focused segments already do. This number has risen within the past year since the last report.

However, not all 3PLs offer reverse logistics services, and less than half said their services are "moderately effective at enabling end-to-end reverse logistics." Further, most 3PL respondents said reverse logistics are "only moderately or slightly important" to their plans for growth in the future.

But is that the correct position to take? Are fleets missing out on load opportunities by ignoring their customers' reverse logistics concerns?

Why do shippers find reverse logistics so challenging?

Companies find reverse logistics challenging because, unlike outbound shipments, it's a complex process. Outbound freight is simple. An order comes through based on demand planning in a company's supply chain. The order then turns into a warehouse order to fill a truck. It then becomes a shipping order or a load, and a truck takes it where it needs to go, Russell Zuppo, VP of consulting services at Uber Freight, explained to FleetOwner.

But with reverse logistics—particularly for e-commerce—the process becomes much more complicated.

Businesses and retailers have always dealt with returns, but the returns process at brick-and-mortar stores has been simplified and ironed out over time. Big retailers have trucks coming to their stores with deliveries each week, and "So it's pretty easy to say, 'OK, let's take one truck and just load it up with all our returns ... and all the stuff that needs to go back.' So you have sort of a built-in network," Zuppo explained.

However, unlike returns that take place at brick-and-mortar facilities—where associates can inspect the goods to ensure they are returnable and if they are the right object, the right size, et cetera—e-commerce returns require businesses to take that process that typically happens in the customer service center and make it remote.

"You've got somebody potentially looking at all kinds of different types of materials, all kinds of different returns, and trying to understand 'Is this something that can and should be returned?'" Zuppo said. "And then it turns into now a sorting process."

For years, companies saw reverse logistics as an afterthought, but now, they are starting to treat reverse logistics as a science, Zuppo said. This is because of the increased volume of returns, which leads to increased waste and environmental harm, as well as the increased cost of inventory handling and the cost of the process that "comes with touching all those goods a second time."

See also: Experts warn fleets to prepare for record-breaking cargo theft in 2024

The challenge with e-commerce is two-fold, according to Zuppo. First, the nature of it creates more returns because customers are making purchases sight unseen. Heather Hoover-Salomon, CEO of uShip, a marketplace that connects shippers to carriers, said the pandemic made e-commerce returns more prevalent, especially returns of larger items.

Before the pandemic, "people were shopping online, but there was a big difference between what they were comfortable shopping with prior to the pandemic and what they became comfortable with during and post the pandemic," Hoover-Salomon told FleetOwner.

Also, because of the pandemic, retailers' return policies loosened, and now consumers expect easy, free returns, Hoover-Salomon said.

The second part of the two-fold challenge with e-commerce returns is there isn't a built-in returns process network that physical stores have. The solution thus far has been the development of collection centers and customers shipping their returns, which Zuppo said adds more costs to the equation.

Retailers, most prominently the larger big-box stores, now must factor in the sustainability aspect of these returns—both from environmental and economic standpoints. They now must take accountability for these items that the customer no longer wants, and the solution is far from straightforward.

See also: Fleets try to meet shippers' newest request: sustainability

For some items, covering the cost of shipping and handling to get the item back, along with the cost and time of processing and sorting, could actually cost shippers more than the value of the returned item. In some cases, retailers refunded customers and allowed them to keep the unwanted item, putting the responsibility for the item's fate in the consumers' hands.

Other retailers choose to donate their goods or sell them to retail warehouses, Hoover-Salomon told FleetOwner.

"From a pure business and cost perspective, you've got to figure out what to do with your inventory," Zuppo told FleetOwner. "Do you dispose of it—is it cheaper to do that? Do you refurbish it—is it worth resale? … There's a lot of different options for customers or for shippers to handle their inventory."

Then some retailers are more concerned with top-line revenue, Hoover-Salomon said, and have even chosen not to process returns as it affects their numbers. But that only leads to warehouses full of goods losing value the longer they sit. As warehouses fill, retailers may then decide to trash the returns. Remember the 9.5 billion lb. of returned goods sent to landfills in 2022 alone?

"This is what I would call a sleeping giant in the industry," Delaney told FleetOwner. "And that cuts across fleet, that cuts across supply chain, cuts across retail. … The challenge is that I don't think anyone has really taken the problem head-on. For some retailers, it's just considered part of doing business."

Where do fleets come in to help address the industry's sleeping giant? Delaney, Hoover-Salomon, and Zuppo share their insight in part two of this feature.

About the Author

Jade Brasher

Senior Editor Jade Brasher has covered vocational trucking and fleets since 2018. A graduate of The University of Alabama with a degree in journalism, Jade enjoys telling stories about the people behind the wheel and the intricate processes of the ever-evolving trucking industry.