For-hire, long-haul, truckload carriers face a significant challenge in recruiting qualified drivers. The American Trucking Associations dubs this issue “the driver shortage.”

“The fact of the matter is, they can’t find enough drivers, and as a result, pay rates have continued to go up in what many deem the worst freight recession we’ve seen in a long time,” Bob Costello, chief economist for ATA, told FleetOwner.

Defining the labor challenge is a fiery, contentious issue. Labor shortages are hard to identify, especially when industry data is sparse. Fleet managers and ATA tend to see a driver shortage, while analysts and groups such as the Owner Operator Independent Drivers Association tend to see a turnover problem.

“When you actually look at what goes on, the problem is retention,” Todd Spencer, OOIDA’s president, told FleetOwner. “Many of those companies will have driver turnover ratios of 100, 150, and even more—and it’s been that way for decades.”

Hanging in the balance is a large sum of money: Drivers are the absolute greatest operational expense for motor carriers, according to the American Transportation Research Institute.

The problem could soon worsen. As the trucking industry prepares for a market upturn and rising freight demand—likely either this year or next—carrier demand for qualified drivers could increase.

The problem: finding qualified drivers

Driver hiring is a major issue for fleet executives.

Driver availability is a global issue

“The driver availability problem is not unique to the United States; this is a global issue,” ATA's Costello said. “It’s not the U.S.; it’s the occupation,”

He pointed to reports by the International Road Transportation Union, a global transportation organization. IRU’s 2022 Global Driver Shortage Report shared industry survey data on driver hiring challenges worldwide: Surveyed carriers said they experienced shortages across Central America, South America, Europe, Eurasia, the Middle East, and Asia.

Raluca Marian, IRU’s director of European Union advocacy, estimated that “the EU will have around 500,000 vacant driver positions by the end of [2022].” IRU’s public survey data found that the percentage of unfilled truck driver positions in 2021 was as high as 18% in Eurasia, 15% in Turkey, and 10% in Europe.

The American Transportation Research Institute found in its annual surveys that the driver shortage was one of the top 10 carrier concerns for over the past decade. For many years, the issue ranked as respondents’ upmost concern. The issue has been an ongoing concern since the 1980s, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

See also: Economy continues to be trucking’s top concern going into 2025

Fleet managers not only struggle to hire drivers but also keep them. Long-haul drivers are hard to retain. A common industry perception is that carriers face driver turnover rates of over 90%.

ATA estimated that driver turnover averaged 93% from 2012 through 2015 and fell to about 83% in 2019. This turnover correlates to fleet safety, too: According to ATRI, research in 1988 found that carriers with high turnover rates had significantly higher crash rates.

ATA and other industry experts often clarify that the high turnover is mostly from drivers hopping between carriers for better pay rates, sign-on bonuses, working conditions, and so on. The nature of long-haul driving is that the work is not limited to a geographic region, allowing career drivers in the segment more competing opportunities than exclusively regional drivers might find.

How bad is the driver shortage?

ATA regularly publishes reports and forecasts on driver shortages. The organization says it pulls from Census Bureau Labor demographics, economic data, and ATA surveys to compare driver demand with available qualified drivers.

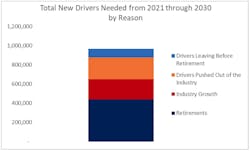

The organization last calculated its shortage estimates in 2021. ATA estimated the industry was short 80,000 drivers—and if trends persist, the shortage could surpass 160,000 by 2030.

Costello is certain driver accessibility has improved since 2021—primarily due to low freight demand—but still faces challenges.

“I guarantee it has gotten better simply because we have been in a freight recession,” Costello said. “But when you consider the quality of the labor, fleets still say that they still have a problem finding quality drivers.”

Costello said that fleets still can’t hire the majority of driver applicants for a host of reasons. Drug use and accident history disqualify many applicants.

Carriers are paying more for drivers

The issue is pressuring fleets to raise driver pay despite restrictively low freight rates.

“[Carriers] still struggle in that long-haul, over-the-road market to find quality, qualified drivers,” Costello said. “It’s one of the reasons why, in a freight recession, pay for them has continued to go up. That alone should summarize where we are with this issue.”

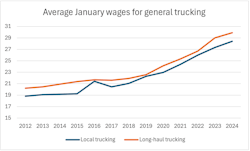

Public data on driver pay is scarce. However, the Department of Labor publishes salary data that can indicate the broad direction of drivers’ wages. DOL publishes wage data for non-supervisory laborers in long-haul trucking, excluding specialized freight. Costello said that drivers make up a strong majority of the workers in that dataset.

See also: Giving drivers a reason to stay

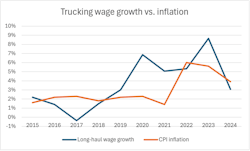

Long-haul wages have not only risen but outpaced inflation for several years. Over the past 12 years, average industry wages each January rose 3%. Most of that pay gain came after the pandemic: Average industry wages since 2020 rose an average 6% annually. The wage gains outpaced the Consumer Price Index’s measure of inflation for most years of the last decade, particularly since 2020.

Costello said that any driver with a clean record who can pass a drug test can hop jobs very quickly, thanks to the high demand for drivers. “I tell people all the time: ‘If you’re a driver like that, and you come to me, I can get you a job this afternoon—even in this market.’”

However, while long-haul wages indeed exceeded inflation, wages among short-haul carriers also grew at a similar rate. The short-haul sector has a lower turnover rate and less concern about a driver shortage.

The shortage may get worse

Industry reports, including ATA’s, predicted in January that U.S. freight demand will rise over the next few years as the economy and key industries grow. While trade wars could bring severe downward pressure on freight demand, carriers still face the risk of a worsening driver shortage.

“The fundamental reasons—which are many—of why we have issues with the driver labor force have not improved,” Costello said. “If freight demand were to pick up significantly, I think you’d be right back to where you were—with the availability of drivers and demand far outpacing supply.”

Truck drivers are an aging demographic. Industry exits due to retirement could significantly reduce the available labor pool. In 2019, ATA estimated the average driver age to be 46 years old. The industry forecasted retirements to be the largest contributor to the driver shortage from 2021 to 2030.

Is the driver shortage real?

Driver recruitment is a real and severe challenge for carriers; however, not every organization agrees with the term “driver shortage.”

Some industry groups and many analysts think the challenge is a turnover problem and not a labor shortage.

“They’re not treated well, and they’re not paid well. There’s really no incentive to stick around—so they don’t,” OOIDA’s Spencer said. “Other segments of trucking—private carriage, the LTL sector—have no such shortage issues. What happens there is drivers generally are treated better, are paid better, and have more predictable work schedules and better benefits.”

Gary Petty, president and CEO of the National Private Truck Council, explained in a FleetOwner post why he thought drivers stick more with private fleets: These groups can make significant investments in selecting and paying drivers—often leaving the fleet operating at a loss—which allows them to spend less time dealing with the consequences of turnover.

See also: How to foster women’s growth in the industry

Industry analysts, economists point to turnover

Industry research firms DAT Freight & Analytics and ACT Research have argued that the challenge facing fleets is more a turnover problem than a shortage of drivers.

“There needs to be more debate as to whether there’s an actual net shortage of truck drivers to drive available trucks or a shortage of drivers wanting to make trucking a career,” Dean Croke, principal analyst for DAT, wrote in a blog post. “One thing is for sure, though: The industry needs help retaining drivers and turning a driving job into a career.”

Both OOIDA and Croke pointed to a study on driver availability by U.S. economists writing for the IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

The authors compared long-haul drivers’ labor data to the expected market symptoms of a labor shortage. They found “no evidence of a sustained driver shortage.” The economists argued, instead, that high turnover caused industry managers to perceive the illusion of a shortage.

“General freight long-distance truckload motor carriers face a structural problem: Their labor market has consistently high turnover,” the authors wrote. “All the evidence about employment in general freight long‐distance truckload is consistent with the view that this labor market works about as well as any other blue-collar labor market in the U.S.”

Another paper by the National Academy of Sciences, commissioned by the Biden-era Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration and conducted by a committee of freight experts, drew the same conclusion. The paper’s authors called claims of the driver shortage “spurious.”

ACT Research also calls “driver shortage” an inaccurate term. The firm regularly analyzes driver availability and uses industry surveys to build a monthly Driver Availability Index for for-hire fleets. The firm says insufficient pay, low quality of life, and restrictive regulations contribute to the labor challenges.

About the Author

Jeremy Wolfe

Editor

Editor Jeremy Wolfe joined the FleetOwner team in February 2024. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point with majors in English and Philosophy. He previously served as Editor for Endeavor Business Media's Water Group publications.