Total Transportation Services (TTSI), a third-party logistics company that manages the import and export of ocean containers, began testing hydrogen fuel cell technology more than 10 years ago. In 2011, TTSI officially placed its first Class 8 hydrogen fuel cell truck into its drayage operation.

TTSI, which is based in Rancho Dominguez, Calif., operates in all major ports across the U.S., either directly or indirectly with partner companies. Its services consist of drayage, warehouse, on-highway specialized logistics for both long- and short-haul, and brokerage.

The first fuel cell truck TTSI tested out was through a joint partnership with Vision Motor Industry, explained Tony Williamson, senior director of automotive maintenance and development for TTSI, during a web-based Advanced Clean Tech (ACT) News education series on the facts of hydrogen fuel cell trucks. TTSI ran the truck from 2009 through 2014 at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

“This truck was a beast, it actually worked,” Williamson said, noting the truck was used to haul shipping containers to and from distribution sites. “This truck had 3,300 pounds of torque. We interviewed the driver one time hauling a container, and he said he had to constantly look back to make sure the container was still there—that’s how much power this truck had.”

For its operational needs, TTSI must have equipment that can run six days per week—four days running two shifts, totaling about 20 hours each day, and Friday and Saturday shifts that run 10 hours each day. The company relies on dependable Class 8 zero-emissions trucks that can move containers and make daily round-trip hauls.

Williamson also noted that the trucks must be able to transport 36,000 to 41,500 pounds, and because there are two bridges at the end of each port, the trucks must be able to pull containers up a 6% grade at a minimum speed of 30 to 35 mph.TTSI has fueling available onsite for the trucks it operates; however, Williamson noted that in order to operate efficiently, the fueling time for fuel cell trucks has to be the same as diesel—roughly anywhere from 10 to 20 minutes depending on the configuration of the truck.

Right now, TTSI is operating the following hydrogen fuel cells trucks: a Kenworth that has been in use for a year-and-a-half; TransPower’s first fuel cell truck, which has been in operation for roughly eight months; and U.S. Hybrid’s second-generation fuel cell truck, which has been in operation for about a year. TTSI is scheduled to receive an additional seven fuel cell trucks in the coming months.

The three fuel cell trucks currently work within TTSI’s duty cycle as 80% of the company’s loads travel no more than 15 to 20 miles one way, Williamson added.

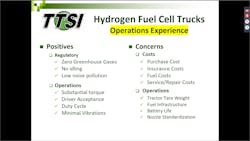

Over the past several years, TTSI has seen some pros and cons using the hydrogen fuel cells. Positives include little to zero greenhouse gas emissions, no noise pollution, plenty of power, and driver acceptance.

“Torque has never been a problem for any of these trucks,” Williamson explained. “They have plenty of power to pull the containers that we move in and out of the port.”

“Driver acceptance has been a big plus for us,” he added. “We have drivers who used to love the diesel trucks but once we brought in these fuel cell trucks, and they got trained and knew how to drive them, they really liked the trucks. Our drivers told us they no longer smell like diesel at the end of their shift.”

Drivers also commented that minimal vibrations on these trucks also have been a perk.

Williamson did, however, point to some areas of concern that the company has had, mainly around cost; the purchase cost for hydrogen fuel cell trucks is higher than their diesel counterparts. In addition, because these trucks cost more to develop and have many different components—batteries, inverters, fuel cells, etc.—insurance costs are higher. Williamson also pointed out that fuel costs for hydrogen in Southern California now range from $12.50 to $16 per kilogram of hydrogen.

And because these are newer vehicle technologies maintenance costs are harder to figure out, he added.

The fuel cells also weigh more than their counterparts, with tractor weight coming in anywhere from 22,000 to 24,000 pounds. Compare that to a conventional diesel truck, which is around 15,500 to 16,000 pounds, or compressed natural gas tractors, which are roughly 17,000 pounds.

Fueling infrastructure is also problematic. TTSI has its own fueling infrastructure, but when trucks go out farther distances and then return, fueling stations are few and far between, or nonexistent. But because TTSI drivers now know how to properly operate a fuel cell, they can make a 60-mile trip and return with no trouble, Williamson explained.

“We believe the fuel cell technology is moving in the right direction. Initially we had issues where the truck wouldn’t even get out of our gate without having a problem. Now, the trucks are able to move 41,500 pounds easily with no issues,” he said. “The investment in the fuel cell technology has improved dramatically. We have new players in the heavy-duty game (the OEMs and integrators). That’s a big plus. And downtime has reduced very quickly. Now, we have more issues on the mechanical side than with the fuel cell technology, which is a big improvement.”

Providing power

Over the last couple of years, Cummins formed a new business power unit that initially focused on battery electric vehicle (BEV) applications in 2018. However, Cummins recently acquired four companies and is now putting increased focus on BEV applications and hydrogen fuel cells, explained Jeff Seger, executive director of growth office and new acquisitions at Cummins.

Cummins recently acquired Brammo, Johnson Matthey Battery Systems, Efficient Drivetrains Inc., and Hydrogenics to expand its electrified power and hydrogen technologies footprint. During the ACT News webinar, Seger said these acquisitions were a substantial investment for Cummins to keep the focus on this new technology at a “very high level.”

Moving forward, Cummins plans to explore working with government agencies to make these developments in new technology more economically sustainable.

“Naturally, we want to make this technology sustainable, and some of these [government] incentives will help us take care of getting infrastructure in place, bringing the cost down, and those kind of things, which are very important to the success of the technology,” Seger noted.

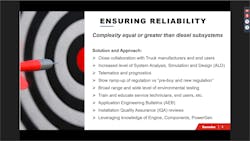

He added that the idea is to get more experience and test different climates, temperatures, altitudes and all environmental factors, which are critical to the success of fuel cell technology. Plus, Seger noted, getting all the electrical components to work in harmony is essential.

“There are also thermal management challenges,” he said. “Fuel cells operate much lower than diesel engines do, so we do have some work to do with the truck OEMs in terms of radiator sizing and other thermal management type balancing.”

“All in all, I think we have a lot of levers and a lot of degrees of freedom, but with that is complexity, and very good systems skills are needed to launch this technology in a reliable way,” Seger continued. “It is very important to get it right and to get it right from the beginning. And the complexity here is quite large.”

Cummins is continuing to work closely with truck manufacturers and end users on all ends of the spectrum, Seger explained, adding that "Cummins is well positioned to address these challenges."

Funding options

During the ACT News webinar, Leslie Goodbody, heavy-duty ZEV infrastructure specialist at the California Air Resources Board (CARB), outlined several incentive programs to help fund and certify zero-emission trucks in California:

- The Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Project

- Clean Off-Road Equipment Voucher Incentive Program

- Volkswagen Environmental Mitigation Trust

- Zero-Emission Class 8 Freight and Port Drayage Trucks

- Carl Moyer Funding for Hydrogen Infrastructure, Vehicles, and Equipment

- Community Air Protection Incentives

- Zero-Emission Drayage Truck Pilot

The North American Council for Freight Efficiency's (NACFE) latest Guidance Report, Viable Class 7/8 Electric, Hybrid, and Alternative Fuel Tractors, noted that commercial battery electric vehicles and fuel cell trucks will be capable of lower total cost of ownership in the 2030 timeframe.

Moving forward, NACFE explained that growing levels of goods movement and increased pressure for cleaner transport are prompting trucking’s growing demand for near-zero or zero-emission solutions.

“As a result, the list of alternative fuels and related powertrains is growing, and these technologies are beginning to reach the point of production-quality vehicles. In the past, natural gas powertrains led the way, but the bulk of the current investment is going into newer options like fuel cells and battery electric vehicles,” NACFE stated. “NACFE believes there is no single solution to replace diesel. Instead, specialization and regional factors are pushing the market to a ‘multi-fuel future’ where many of these technologies will coexist.”