As excitement of self-driving trucks grows, fleets will soon have products to choose from

Excitement—and derivations of it—is a word dropped in almost any conversation with anyone at an autonomous trucking company. From the prospects of moving freight farther, faster, and safer in robotic tractor-trailers to just the concept of self-driving vehicles becoming reality, it’s tough not to be excited if you’re working within the future of transportation.

“It’s a really exciting time,” Jason Wallace, head of marketing at TuSimple, told FleetOwner during the Consumer Electronics Show 2022, held in Las Vegas the first week of the year. TuSimple raised the excitement level several notches in 2021. It became the first autonomous driving company to go public while growing its fleet to more than 70 heavy-duty robotic tractors (50 in the U.S. and others in Europe and China). And just before the new year, it completed an 80-mile freight route with no human on board, the first such run on public roads with a Class 8 truck.

But as these exciting concepts move closer to an exciting reality, how will fleets be able to harness the excitement?

“Engage in the conversation early,” Andrew Culhane, chief strategic officer for Torc Robotics, told FleetOwner during a recent visit to its testing facility in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “From our view—and what seems to be the broader industry—this technology isn’t a question of if but when.”

Culhane said Torc already is having conversations with interested fleets. And some advice he gives them is to think about their current route structure and network design and how an autonomous middle mile could change them. That could include changing how a fleet looks at its various regions and considers using its autonomous freight routes to link multiple regions or even hook up with other carriers’ networks.

“From a middle-mile piece, are there other models that are going to enable more efficient, more profitable business for them?” he said. “For us, it’s really important to make sure that as we bring this product to market, we’re thinking about that.”

Future freight networks

The current U.S. freight networks date back to World War II, Culhane noted. “I think autonomous has that ability to supplement the way people might have thought rail would have,” he said. “Where there are those dense lanes that autonomous can serve in that middle-mile capacity so that we have much more regional focus. COVID has kind of pushed freight to that mindset of figuring out how to do better regionally before you try to do everything. That autonomous middle-mile can give you more of that focus.”

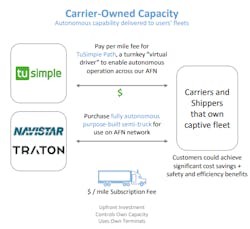

TuSimple’s Autonomous Freight Network (AFN), which stretches from Arizona to Florida, is the largest of its kind in the U.S. It has been moving freight for various fleets for years as it continues to test its system so it can offer a product to fleets by the middle of the decade.

Wallace said TuSimple already has more than 6,700 reservations for the vehicle it’s building with Navistar, a self-driving International LT Series tractor expected to be available within a couple of years.

“Right now, fleets are able to buy a purpose-built truck from Navistar that is equipped with TuSimple’s technology,” he explained. “Once you have these assets, we operate the truck for you. You tell me, for example, that you need this truck to leave on Monday at 8 a.m. and go from Phoenix to Orlando. The way it works is—you don’t have a human driver in the vehicle—you’ll pay TuSimple a per-mile fee.”

That per-mile fee is part of a subscription program for fleets called TuSimple Path, which the company describes as a “turnkey virtual driver” that works across TuSimple’s AFN. So the fleet owns the vehicle while TuSimple operates it autonomously, essentially acting as a dispatcher with more control.

“We monitor the safety of these vehicles from end-to-end,” Wallace said. “We’re essentially responsible for the safety of these vehicles from end-to-end. Asset owners are controlling their capacity while we make the physical moves; and you pay us a per-mile fee, which is far less than what you’d be paying with the human driver.”

While the actual equipment will cost more than a traditional Class 8 tractor, autonomous trucking companies and OEMs who spoke with FleetOwner recently said these robotic trucks would pay for themselves over time.

Along with saving the costs associated with human drivers, robots can get better fuel efficiency than most human drivers. Nearly every autonomous trucking company boasts fuel savings around 10% compared to human-operated trucks. Over the course of 160,000 autonomous miles moving UPS freight (with a safety driver on board), TuSimple reported 13% fuel savings.

The autonomous fleet product

“In a perfect world, these behave like your best driver, on their most patient day, with a full night’s sleep and a great cup of coffee,” Torc’s Culhane told FleetOwner at its testing facility in November.

“You’ll see better fuel economy and less wear and tear,” he added while standing beside a prototype Freightliner Cascadia equipped with Torc’s Level 4 autonomous technology. “These vehicles drive extra smooth. They don’t want to be jerky. They don’t want to be impatient.”

Culhane and Torc have been meeting with fleets as it develops that prototype truck into a work truck. “These are million-mile assets. We’re working to understand what that’s going to take from a ruggedness and reliability perspective. We’re also having those conversations with the fleets and with the dealers to discuss how we are going to service these things. We don’t want to add any more cost or operational burden. So we’re trying to make sure we do that in the smartest way possible, engaging in those conversations with the fleet very early on to ask, ‘What works operationally?”

This is all part of that full-service fleet product that autonomous trucking companies are developing for the fleets of the future—a future that is just years away. Most large truck OEMs have partnered with self-driving technology providers to offer fleets Level 4 autonomous vehicles.

Daimler didn’t just team up with Torc—the OEM acquired a majority stake in the robotics company while allowing it to develop its technology independently. “Collectively, this is Torc and Daimler because we need the hardware to go with (the technology) to create that fully-enabled self-driving truck,” Culhane said.

Culhane said that fleets who buy the product he and his team of engineers are developing among the mountains of New Mexico could be tied into a carrier’s telematics and TMS, which would be connected to Torc’s mission control. “That overall system empowers fleets to run that self-driving truck hub-to-hub or within their network,” he explained. “While it isn’t a solution to everything, it does provide that hub-to-hub, middle-mile autonomous truck.”

Technology and truck partnerships

While Culhane said this past fall that Torc and Daimler are still finalizing how they will sell their finished product to fleet customers, rival Paccar’s strategy to bring autonomy to the fleet market includes its partnership with Aurora.

The maker of Peterbilt and Kenworth trucks is building the Aurora Driver—the equipment and technology that controls the tractors—into its flagship long-haul trucks, Stephan Olsen, general manager of the Paccar Innovation Center, told FleetOwner during CES 2022.

“Paccar, these guys are experts; they’ve been doing this for 100 years. They make very good trucks and they will sell the trucks to the fleet,” Richard Tame, CFO at Aurora, told FleetOwner while standing beside an Aurora Driver-equipped Peterbilt Model 579 at CES.

Tame said fleets would order the truck directly from an equipment-maker such as Paccar and purchase the Aurora Driver as an option. “Then they would buy the truck from Paccar—maybe they use Paccar financing,” he explained. “Paccar would still offer all the aftermarket services of the vehicle and things like that. Then they would enter into a separate agreement with Aurora to drive the thing. So Paccar gets the revenue they used to get and we get the revenue for being the driver on a kind of subscription per-mile basis.”

Along with Pacaar, Aurora partnered with Volvo Trucks to develop an autonomous VNL 760 tractor for North American fleets. The subscriptions service, Aurora Horizon, would allow fleets to run freight nearly 24/7 on driverless trucks. Because without a driver, there would be no hours-of-service regulations to follow. The company is yet to share the price of Aurora Horizon.

“Aurora Horizon will provide carriers and private fleets with a reliable and scalable driver supply powered by the Aurora Driver and a powerful suite of tools designed to integrate these vehicles with existing operations and maximize their uptime,” the company wrote in an October 2021 blog post announcing the future service. “To ensure carriers have confidence in the safety and reliability of Aurora Horizon at launch, we’re working with our OEM partners and carrier customers to refine our product through a series of commercial pilots as part of our Aurora Driver Development Program.”

The road to success doesn’t have a driver

Tame said that Aurora is targeting a driverless commercial launch by the end of 2023. And while almost all public testing of robotic trucks includes a safety driver and engineer or another monitor in the cab, Tame said the road to success for his company and fleets is driverless.

“We don’t have a commercial product with a driver because these sensors are expensive,” he said, pointing to the lidar-, radar-, and camera-equipped on the Class 8 Peterbilt. “Having an expensive, kitted-out truck with a safety driver is not a product.”

The first fleets that will get a chance to subscribe to Aurora Horizon would likely be those operating in Texas, Tame said. “There will be a specific lane that it can operate in. And we’ve said it will go terminal-to-terminal: Autonomous all the way on the highway to short surface road driving to the terminal. And then it’ll just kind of grow from there.”

Tame said that Aurora doesn’t have subscription number goals beyond “as many as we can. There are a lot of trucks in the world. There are a lot of trucks in the U.S.

“This doesn’t, especially in the short term, replace human drivers,” Tame said. “It just kind of eats into the shortage.” And without the HOS limitations put on drivers, self-driving trucks would be ideal for long routes. “So what might happen is that the very long routes—that force drivers to be away from home all the time—get taken over by something like this. Then those people can start going to more regional driving and can get home every night. So it’s not really a replacement story. It’s sort of an implementation story.”