Considering the sensation that 3d printing, a.k.a. additive manufacturing, has created in the public’s mind for the last several years, you wouldn’t think it dates back to the Reagan administration. But it does, and the technology seems to have hit a stride at last in the trucking and automotive worlds for things like prototyping concept vehicles or tooling up parts molds faster and cheaper than traditional manufacturing allows.

Maybe that’s 3D printing’s natural application in those industries, or maybe there’s more. Fleet Owner reported last year on its inroads and uses in trucking, and the latest to have sprung up and shown promise was making spare and repair parts on demand.

In Europe, Mercedes-Benz Trucks said it would start 3D printing upwards of 30 spare parts for its Actros series trucks and has plans to do more. That began last fall. Ford Motor Co., in another example, has made progressive use of 3D printing for years, going back to owning one of the very first printers made and many subsequent ones. Ford has used the technology mainly to evolve and speed up the prototype process for cars and trucks, but also began limited parts production in the 2010s.

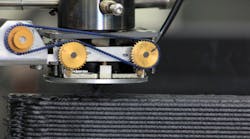

Most 3D printers use digital blueprints to put down layer by layer of various materials that cures or is hardened, constructing many possible items as they’re needed. Beyond prototyping and one-offs, though, the question now is whether 3D printing is just a sideshow act drawing attention for its novelty—or it actually could change manufacturing and supply chains as we know them.

On-demand, distributed production

What does 3D printing offer in truck and other vehicle maintenance? Traditionally, if you’re manufacturing replacement parts, the OEM or a supplier needs tooling, molds and so on to make each part and a production run of it. You’ll need to distribute the part wherever the corresponding vehicle is in service—which could mean nationally, internationally or globally—and the item is stored or warehoused at places like dealerships and service centers for however long it’s required.

That might be fine for large-volume, fast-moving inventory items, but it gets costlier with less return on investment for progressively lower-volume, slower-moving inventories. In the case of fleets and trucking companies, far fewer of a particular model Class 8 heavy truck are made and sold each year than Toyota Camrys, for example, and those big trucks may have a very large service area spread.

Time is also a factor—including time to produce and distribute rarer parts particularly—and as a vehicle model ages and starts disappearing from the roads, there’s less call for those parts. With trucking, sometimes due to costly features required for new models or even a classic look of an older one, you’ll find many older trucks still in use. Regardless of what trucks they’re running, no fleet or truck driver wants to wait around for parts to arrive after a breakdown. OEMs have been looking to 3D printing for possible solutions.

“Across all the verticals I’ve seen and been involved with, the 3D printing companies and materials manufacturers want to develop a process that’s adaptable to in-service production parts,” says Gregory Haye, general manager of the Knoxville, TN, microfactory of Local Motors. This young, Phoenix-based vehicle manufacturer turned heads last year with its mostly 3D-printed, self-driving people transport called Olli, which started rolling last summer in National Harbor, MD, a shopping and convention center destination.

“That’s the jump that many of the 3D printer manufacturers are trying to make,” Haye contends. “They want to transition additive manufacturing to being part of the production process, not just a means to prototype.”

Considerations for parts

Another trailblazer in 3D printing, Cincinnati Inc.—which has also been in the traditional manufacturing business over a century— showcased its unique Big Area Additive Manufacturing (BAAM) technology last year at the NTEA Work Truck Show with a 3D-printed Shelby Cobra replica. While Cincinnati’s core business is making traditional manufacturing equipment like lasers that cut plate and sheet metal or metal-bending and -forming presses, BAAM 3D printing made waves because it can print large items within an 8-ft. wide, 20-ft. long, 6-ft. high working space.

Local Motors purchased three BAAM machines and uses them to make things like vehicle bodies or panels. Addressing potential applications for 3D printing in maintenance and spare parts, Matt Garbarino, director of marketing at Cincinnati, names several initial considerations: material, size and finish.

BAAM machines, for example, are designed to print thermoplastics, although Garbarino says metal printing is a future consideration. The most durable, rigid material BAAMs print today is an ABS plastic-carbon fiber composite, so a parts maker would need to determine if that’s suitable for an item it intends to produce. The same goes for other 3D printers and whatever materials they’re able to use, including various plastics and metals.

Unlike BAAM, most 3D printers today are of the desktop variety, so the items they’re able make are much smaller. The printer’s footprint dictates potential end product size—that second consideration regarding the technology’s applicability—and also segues to the third.

“When you’re looking at doing large-scale 3D printing, for example, you have to pump out a lot of material,” Garbarino says. “The tradeoff when you’re pushing 80 lbs. of material per hour out of an extruder is that you won’t get the fineness or smoothness on the product you’re printing, so you’re likely going to have a finishing operation.” That could mean machining, sanding or filling the printed item, he notes.

Smaller 3D printers can produce only smaller items, but they’re also printing finer layers and may be able to make products with a suitable finish as-is—so there are benefits and drawbacks with various 3D printing technologies and printer sizes. “If you think about the work truck industry, it does lend itself to a larger scale; if you wanted to print a component for a cab or maybe part of a bed, you could do it,” Garbarino tells Fleet Owner. “In the applications we’re looking at, in most cases, there’s a finishing component.”

Evolution: Digital inventory

New methods of 3D printing are adding some further depth to this discussion. Topping that list is a company launched as Carbon3D and now rebranded simply Carbon whose technology was inspired by the movie Terminator 2: Judgement Day. The film’s groundbreaking special effects depicted “liquid metal” robots able to morph into any shape, sometimes springing up out of a puddle of material.

Carbon’s Continuous Liquid Interface Production, or CLIP, 3D printing bears a strikingly close resemblance. CLIP printers use a bowl of polymer resin and create an item’s structure in the liquid using UV light, and the object is subsequently heated and fully cured in a second stage. It’s much faster than typical 3D-printing, according to the company, and can make very durable items with smooth surface finish hot off the presses, as it were.

“In trucking and heavy equipment like agriculture and construction, you have these vehicles or pieces of equipment that have long service lives,” notes Sasha Seletsky, director of applications engineering at Carbon. “They have a pretty long tale of low-volume or high product mix, and that’s always a challenge from a spare parts perspective to support.”

There are other costs and complications: he points out that a supplier may require a last-time buy at the end of a part’s production run or have to store the part’s tooling and molds, with additional setup costs/ minimum quantities for any future production. Over time, production tools could get damaged or rusted, the supplier could go out of business or get acquired and production information isn’t transferred properly.

“Companies have so much cash tied up in these warehouses, tools and parts, so they’re very interested in this concept of a digital inventory,” Seletsky says. “Imagine that all of your parts just live in the cloud, in CAD [computer-aided design], in digital form—and as demand comes in, you essentially just print the parts as you need them. You don’t need tools sitting in a warehouse, because you can have printers in different locations.

“You can reduce lead times and the cost of logistics by printing the parts where you need them and when you need them,” he continues. “It’s essentially distributed manufacturing. I’d say that was originally the vision with 3D printing; it just hasn’t been realized. Companies are now starting to see the potential again, and there’s definitely a lot of promise there.”

Show me the money

As with most things, this isn’t just a question of 3D printing’s ability to deliver consistent, suitable spare or even production parts. For many parts that go into trucks and other vehicles, additive manufacturing technology can now produce them. But is it cost-effective?

For the time being, the answer may be no. Global delivery and logistics company DHL Express examines this potential for 3D printing in a Nov. 2016 trend report, “3D Printing and the Future of Supply Chains,” noting Mercedes-Benz Trucks’ use of the technology in producing spare parts. “DHL has tested this future concept by 3D-printing replicas of spare parts that the organization currently stores for automotive and technology customers,” the report states. “These tests concluded that the costs for materials, hardware and handling of the 3D-printed spare parts did not yet result in a viable business case.”

DHL also finds that 3D printing parts can take too long, “with some complex and larger parts taking several days to print.” The technology’s progression will likely solve that problem, but the cost issue is the bigger one.

But if the right network of 3D printers were established and at the ready, it would likely spell the end of the cost debate. DHL expects that will be the case in the years to come because manufacturers have such sizeable resources tied up in spare parts. “It also builds inefficiency into the supply chain, as excess inventory is being produced with no guarantee that all parts will ever come into use,” the report states.

Cincinnati’s Garbarino agrees, noting that’s why the company has been showcasing its BAAM and also smaller-scale 3D-printing technology in various industries. “We had a lot of conversations with companies at the Work Truck Show last year and afterward,” he tells Fleet Owner. “There’s no question that companies would explore getting spare parts, small production runs and things like that done; the question is, who will do it?”

“That’s where I see there’s a big opportunity,” he adds. “It’s not just OEMs buying and strategically locating their own 3D printers to do tooling, prototyping or spare parts, it could be a company that doesn’t make its own stuff but is looking to do contract work.”

So it might be that some third-party player—imagine a FedEx Office kind of business where a variety of items could be 3D-printed quickly and cost-effectively—could unlock the technology’s true potential in the spare parts segment. In that vein, Garbarino points out that Akron, OH-based Additive Manufacturing Solutions purchased a BAAM machine late last year intending to do contract work across multiple industries.

“Is that specifically for the work truck or trucking industries? No, but it could be,” he contends. “I would suspect there’s going to be many other companies that will do this, too. There’s no question there’s a business plan to be made from owning a machine like this and being able to do this stuff.” In its report, DHL points to Kazzata, another startup 3D-printing business that aims to create an online digital warehouse “effectively establishing a CAD repository for obsolete and rare parts.”

Special apps and special ops

Where else might 3D printing for spares and repairs take hold? Like other technologies—night vision and drones are two examples—the military may help blaze the trail as the tech picks up steam on the civilian side of things. Garbarino notes that an aircraft carrier is one place a 3D printer could be of particular use.

“They’ve got their own machine shop and fabrication shop onboard, because they’re out there and they have to be self-sufficient and make their own stuff,” he says. “So having something like a BAAM machine on a carrier could be very useful, and we’ve had some conversations with the military to see what might be feasible.”

Carbon’s Seletsky points to examples of a vehicle parts where 3D printing has proved a better solution than traditional manufacturing. California-based electric motorcycle startup Alta Motors, for one, tapped Carbon’s CLIP technology to produce diagnostic connector housings.

“Their motorcycles aren’t Internet-connected but have a lot of electronics, and dealers wanted to be able to plug in and download operational information and run diagnostics,” Seletsky tells Fleet Owner. Alta needed a diagnostic module housing, but only on the order of several hundred units since the company had only sold a limited number of the motorcycles. A traditional manufacturing run was too costly, so Alta tapped Carbon’s 3D printing for a solution.

“That’s the product that they’re shipping,” Seletsky says. “It’s not a bridge solution, it’s not a prototype—it’s the final product they’re sending to dealers.”

Local Motors’ Haye also notes that 3D-printed parts can offer advantages over traditionally manufactured ones. Take vehicle structures, for example: “Traditionally, if you have a skeletal structure underneath and body structure on top, those can’t be one,” he explains. “But with 3D printing, it could be a fully engineered structure. You’d have some sort of spatial gap in there where you’re using different in-fill patterns or internal geometry that can support the body panel, which could also give advanced energy absorption properties for safety.”

The consensus from Local Motors, Cincinnati and Carbon is that yes, 3D printing for production and maintenance-related parts has strong potential; it’s just a matter of time and maybe the right entrepreneurial spark to catch fire. And though Ford and Mercedes-Benz Trucks didn’t have updates just yet on their use of 3D printing, both OEMs told Fleet Owner there may be more developments later this year.

“And there are numerous large companies, let’s say in the logistics world, looking at the distributed manufacturing model for parts supply in various industries,” Haye notes. “It’s on a lot of people’s radar; I can confirm that.”