Cummins is finding more than one way to decarbonize fleets

COLUMBUS, Indiana—The road to fleet decarbonization is complicated. While traditional fossil fuels have powered the trucking industry for generations, thousands of engineers at Cummins are working to reduce emissions from internal combustion engines and new zero-emission technologies for future fleets.

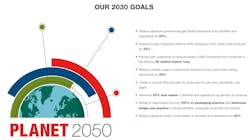

That future is getting closer as federal and local regulators target 2027 for heavy-duty truck and engine reduced emission standards. Between now and the middle of the century, the Tier 1 commercial vehicle supplier is developing more than one way to power a truck as part of Cummins' Destination Zero strategy. That strategy includes spending more than $1 billion per year on research and developing future power technologies on the way to net-zero emissions by 2050.

See also: Zero-emission future can be profitable for truckingLooking down the road at future power solutions can be a lot for fleets that want to start planning now for that future.

"We've got 100 years of understanding what those customers are going to do with that equipment, how they like to be supported, and what they're trying to get accomplished," Brian R. Wilson, Cummins' new power GM of electrified components, told FleetOwner during a tour of the Cummins Technical Center, one of several sprawling complexes the company maintains here in central Indiana. "And we can design the stuff to be able to go do that."

There are five power technology choices facing truck OEMs and fleets: diesel, natural gas, hydrogen engines, hydrogen fuel cells, and battery-electric. "Diesel and the natural gas are obviously the incumbents," Jim Nebergall, Cummins' GM of hydrogen engines, said during an interview at the Cummins corporate office headquarters in downtown Columbus.

While natural gas is near-zero emissions, hydrogen and battery-electric offer zero tailpipe emissions. Nebergall said that while some fleets are all-in on natural gas, others are looking to jump from diesel to zero-carbon options because they view natural gas as a bridge to newer power technologies.

More than one way to decarbonize a truck

"The nice thing about Cummins is we don't come in selling one," Nebergall said. "Others might be more monolithic and tell you that battery-electric will solve all of your problems. But we try to look at a broad solution set of options."

Puneet S. Jhawar, Cummins GM of global natural gas business, said the vastness of Cummins' focus makes it the place to be. "A lot of people want to work on the new technologies," he told FleetOwner. "I think Cummins is one place where you can work on almost all the technologies. There's nobody who stops you and says, you've got to be on the diesel side, or you've got to be on the natural-gas side.

See also: Fleets and their customers are driving decarbonization

These days, Jhawar said he and his colleagues at Cummins are getting more questions from fleets about transitions from diesel. Many of those queries center on maintaining non-diesel engines. "That is why the fuel agnostic platform is helpful," he explained. "Because we're trying to get to a point to say that 50, 60, 80% of the parts are going to the common head deck below."

Two of every three long-haul trucks in North America are powered by 15-liter diesel engines. Cummins' fuel-agnostic platform is based on the power technology that OEMs, fleets, and drivers are familiar with. The platform is built for diesel, natural gas, and hydrogen fuels.

Earlier this month, Paccar announced it will offer the Cummins X15N natural-gas engine in Kenworth and Peterbilt trucks. With renewable natural gas (RNG), also known as biomethane, the X15N can reduce greenhouse gas emissions from a 90% reduction to carbon neutral or even carbon negative, depending on the bio-source, Jhawar explained.

Below the head gasket of the diesel, natural gas, and hydrogen engines are similar components, which means fleets can stock similar parts, no matter which fuels they use, he said. The components above the head gasket will use different components. "It is still an engine, which makes it easier to train the technicians that you already have," Jhawar added.

Hydrogen ICE paves way for fuel-cell power

Cummins' 15-liter hydrogen internal combustion engine, the X15H, is built on the same fuel-agnostic platform and is expected to go into full production in 2027. Its development will also help the power company pave the way for fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEV).

Cummins' fourth-generation fuel cell will power an electric Freightliner Cascadia, the two companies announced earlier this year. Four new things make up a fuel-cell vehicle, Nebergall explained: fuel-cell stack, batteries, traction motor, and hydrogen fuel storage.

"Each of those is expensive—anything new is expensive," he noted. "Of those four things, there's one thing that's common with the hydrogen engine and that's fuel storage. Everything associated with putting hydrogen on the vehicle is common within fuel cells or an internal combustion engine."

See also: The dawn of hydrogen trucks

The hydrogen engine Cummins is developing will benefit future fuel-cell vehicles, Nebergall said. "Because we can go early with an engine, we can go fast," he explained. "It's relatively cheap. Then there's only one expensive thing on the truck—that's fuel storage. But we can help drive scale to those components by launching an engine. So if we're successful with the engines, we're driving scale to make more of these tanks, sell more, and have truck OEMs integrate the fuel storage. That gets the cost down and it helps fuel cells as well."

Power diversification is critical to creating a sustainable supply chain—because, unlike traditional diesel, the newer fuels don't fit into every duty cycle in the industry.

There won't be one winner between hydrogen and natural gas, Nebergall said, because they both have pros and cons. With green hydrogen, fleet operations provide actual well-to-wheel zero-carbon emissions. "With natural gas, you have to tell a story around renewables," he explained. "This is something that would have been let into the atmosphere through some other means. It's been captured and converted. There's still tailpipe carbon—but the carbon would have gone into the atmosphere anyway. So it's a longer story."

Still waiting on commercial EV reliability

The simplest way to cut tailpipe emissions is to remove the tailpipe. But integrating tailpipe-less battery-electric vehicles into most over-the-road fleet operations isn't simple.

When Wilson speaks with fleets about electrification, the cost curve and timeline for EVs to match the power and range of diesel-powered equipment are among the most common concerns. He said fleets are still waiting to see how reliable commercial EVs are.

"They want to understand that better," Wilson said of fleets. "And they want to know about improvements in energy density so they can start planning routes. Certain routes are tailor-made for battery-electric right now. Essentially the longer the routes are, the more challenging it is to meet the duty cycle today. So they asked about energy density improvements on the battery side—and when they can start planning for 150 miles and 200 miles and then 300 miles."

See also: Shippers want to decarbonize, trucking can help

Right now, Wilson and his team are more focused on medium-duty EVs because the batteries are more capable for those smaller vehicles and shorter routes. But some heavy-duty segments are good fits for battery-electric conversions, such as drayage and depot transportation along with urban delivery. The battery needed to power a heavy-duty EV is four to five times larger than what a medium-duty truck needs, Wilson noted.

"But for right now, the medium-duty kind of stuff—where it's coming back to the same home base, where you don't have such a heavy load that requires fleets to make trade-offs between the weight of the system and what you can actually carry—those are the right applications that are going to go first."

While the size and weight of batteries powering Class 8 trucks can top 10,000 lb. to get more than 300 miles of range, Wilson said technology is improving. Like cell phones, which use smaller batteries today that last longer and provide more power than what was used years ago, vehicle batteries will eventually become smaller, lighter, and more powerful, Wilson said.

"There are real improvements happening on the battery side to increase the energy density, so you're adding less weight," Wilson said. "And certainly e-axles are going to help from that perspective, too. The more metal you take out, the less weight—so that's going to be a big deal to the overall powertrain."

This year, Cummins acquired Meritor, which among other things, develops electric powertrain solutions for commercial vehicles. "Together, Cummins and Meritor will move further and faster in developing economically viable decarbonized powertrain solutions that are better for people and our planet," Cummins President and CEO Jennifer Rumsey said after the acquisition was finalized in August.

How fleets can develop decarbonization strategies

The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act will move more money into the commercial vehicle industry's decarbonization efforts that could drive up volume, improve scale, and lower costs, according to Wilson.

"To have that partnership with the government to help drive down that cost curve is going to be super important," he added. "There's also funding for the actual research being done by the folks that are actually trying to improve the battery energy density so it can get smaller and weigh less. And then there's money tied to the charging infrastructure."

See also: Cummins names Ramsey next CEO

"You have to find partners willing to have the real conversations around what the right product is for you—and whether that route or duty cycle is the right duty cycle to electrify or whatever the best technology is."

Then, fleets need to develop a charging infrastructure plan, which Wilson called "a big challenge."

It's also essential for fleets to begin testing future technologies. "They should be pushing for demos just to see for themselves," he suggested. "See how drivers like it. See what routes it actually works on. See the kind of impact on the community it has. And see the kind of feedback you're getting from people that see your truck go down the road. So just getting out there and trying is important."

Operating fleets is getting more complicated

"It's a more complicated time right now—just by the way regulations are happening and different things are happening around the globe," Wilson explained. "There's also a larger option of technologies, which will work for certain applications than there were 15 years ago. But even 15 years ago, we had clean diesel and natural gas. And we were working on hybridization.

"Now you can add hydrogen fuel cell, hydrogen combustion engine, and battery-electric. There are just a lot more technologies you have to choose from," he continued. "That's why it's important for these fleets to have folks they can trust to have an open and transparent conversion. Because there is no one solution that's right for everything—and there probably won't ever be."

Wilson said big fleets do the most alternative technology experimentations to see what works best. "Smaller fleets are probably going to be a bit more conservative and stick with what they've got until they see it played out in some other area," he said.

Local regulations and incentives will encourage some fleets to move toward specific technologies. "Big fleets are going to try it all," Wilson predicted. "They're going to see what actually works and have a real conversation to see what the maintenance costs along with reliability."

Cummins' long-term development plan lowers emissions this decade because it incorporates well-to-wheel emissions reductions by pairing the power technologies that are ready with the fuel infrastructure available. The company's Destination Zero plan develops wide-scale adoption with various technologies.

"Because we're not pushing a single solution, we can go to the fleets and have more of a consultative discussion—as opposed to coming in and saying what the right solution is," Wilson said. "We have their duty-cycle information because we sell them the engines. So we can sit down with them and talk about a route they're running and why a certain technology makes sense in these routes."

About the Author

Josh Fisher

Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief Josh Fisher has been with FleetOwner since 2017. He covers everything from modern fleet management to operational efficiency, artificial intelligence, autonomous trucking, alternative fuels and powertrains, regulations, and emerging transportation technology. Based in Maryland, he writes the Lane Shift Ahead column about the changing North American transportation landscape.