Key takeaways

- Diesel dominates Class 8, but EPA 2027 rules may add ~$20K per truck—fleets must weigh emissions gains against higher equipment costs.

- Alt fuels like CNG, propane, ethanol, and biodiesel cut emissions, but range, MPG, and infrastructure gaps limit duty cycles.

- Drop-in fuels—renewable diesel and RNG—offer lower carbon without new engines, easing adoption for existing fleets.

Even those not in the transportation industry are keenly aware of gasoline and diesel fuel. The two fuel types are the most popular among all motor vehicles worldwide.

This is part of FleetOwner's Fleets Explained, a Trucking 101 series to break down aspects of the trucking and fleet management industries. You can read more from the series, launched in May 2024, at fleetowner.com/fleets-explained. To submit topic ideas, clarifications, and corrections, email [email protected].

But what many might not know is that there are multiple fuel types available for vehicles—some that can be immediately used as a direct replacement for your current fuel. That is, if you can find them.

This FleetOwner Fleets Explained article details the different types of fuels powering trucking and commercial fleets, where they are used, and where to find them. Some have been around for more than a century, and others are emerging as transportation considers alternatives to traditional power.

What is diesel?

Diesel is trucking’s favorite fuel, powering 76% of all commercial trucks, according to the Engine Technology Forum. More specifically, diesel powers 97% of Class 8 trucks and 75% of smaller medium-duty trucks. It’s a popular fuel for heavier applications because of its performance and efficiency, offering a “greater energy density than other liquid fuels,” therefore, providing more “useful energy per unit of volume,” the U.S. Energy Information Administration states.

Diesel fuel also produces harmful emissions from the tailpipe, both gaseous and solid. The solid is known as diesel particulate matter, which are small, inhalable particles containing harmful chemicals that can lead to health problems, according to California Air Resources Board. Diesel’s gaseous emissions include oxides of nitrogen, which can harm the environment.

Diesel-powered vehicles are getting cleaner, however. So much so, that the American Trucking Associations stated: “Over the last three decades, emissions from new trucks have been reduced by more than 98%. It would take 60 of today’s trucks to generate the same level of NOx and soot emissions coming from a single truck back in 1988.”

Those diesel emissions will be decreased even further for truck models beginning in 2027 due to the EPA’s Clean Trucks Plan. The Clean Trucks Plan is a string of regulations seeking to decrease overall emissions from trucks. For example, EPA’s latest NOx regulation under the plan seeks to decrease NOx emissions, which are already near-zero at 0.20 grams per brake horsepower hour, by 82% to 0.035 g/bhp-hr, Allen Schaeffer, Engine Technology Forum executive director, told FleetOwner-affiliate Fleet Maintenance in 2023.

While the Trump administration seeks to roll back the EPA 2027 regulation, along with other regulations targeting the heavy-duty trucking sector, if these regulations remain in place, it could make trucking that much more expensive.

Diesel engine and truck manufacturers are now in the process of designing and engineering these cleaner engines, and they have also warned that these modifications will cause the price of a truck to skyrocket. During a media briefing at a Volvo Trucks assembly facility in July 2024, Magnus Koeck, Volvo Trucks North America's VP of strategy, marketing, and brand management, said the cost of a new Class 8 truck could rise by $20,000.

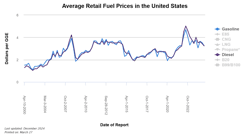

Another downside to diesel is that it suffers significant price volatility. It's one of the highest expenses for fleets, but it's also one of the most unpredictable. For example, fuel prices fell and rose more than 20% over the course of just a few months in 2023, according to the Fleets Explained breakdown on fuel pricing.

What is gasoline?

Gasoline is the trucking industry’s second-favorite fuel, powering 22% of all commercial vehicles in the U.S., according to the Engine Technology Forum. Many lighter-duty vehicles are powered by gasoline, and because of their lower upfront costs compared to diesel, light-duty fleet owners might be more inclined to purchase them (depending on their needs, of course).

Gasoline engines don’t produce as much torque as diesel engines due to lower compression ratios, combustion speed, diesel fuel’s energy density, and other reasons; therefore, gasoline-powered vehicles shine in applications where diesel engines would be unnecessary or more challenging to maintain.

An example is an application with heavy urban driving. The constant stop-and-go of city streets can wreak havoc on a diesel engine’s diesel particulate filter, and applications that don’t require daily hauling or towing render a diesel vehicle basically unnecessary—especially in low-mileage applications that don’t give the diesel engine the breadth to make up those efficiency gains.

While performance efficiency is diesel’s bread and butter, gas-powered vehicles have the upper hand with maintenance.

Unlike diesel-powered vehicles, gasoline-powered vehicles do not have a diesel particulate filter, which requires regular maintenance and attention. This additional maintenance can add up over time and, depending on the application, can negate any efficiency advantages a diesel engine might have over a gas engine.

Gasoline, like diesel, is refined from fossil fuels and has its environmental drawbacks. Some would argue that gasoline is even more harmful than diesel because of its inefficiency. At one time, European governments encouraged diesel engines over gasoline engines, according to Azo Cleantech, citing that diesel engines emit fewer greenhouse gases than gasoline engines over their lifetime. However, because gasoline engines emit fewer nitrous oxides compared to diesel, it is seen as a more environmentally friendly fuel.

As with diesel, gasoline is a commodity with similarly unpredictable pricing.

What is ethanol?

Ethanol is an “alcohol fuel” blend of gasoline and ethanol. The most common ethanol blend is E10, made up of 90% gasoline and 10% ethanol. However, ethanol blends can reach as high as 83% ethanol and 17% gasoline, known as E85, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

Ethanol is made from starch- or sugar-based materials, such as corn. This material is referred to as “feedstocks.” That feedstock is then taken to an ethanol production facility to be converted into fuel via a fermentation process.

The EPA approved the use of E10 in any internal combustion gasoline engine and the use of E15 fuel (a blend of 10.5% to 15% ethanol) in gasoline vehicles MY2001 and newer. The use of E85 requires a flexible fuel vehicle. Fortunately, many vehicles on the market are flex fuel, including popular light-duty fleet vehicles. Fleet owners can check whether their vehicles are compatible with higher ethanol fuel blends through DOE’s alternative fuel and advanced vehicle search engine.

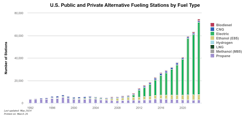

According to the EIA, fuel ethanol was the most produced and most consumed biofuel in the U.S. in 2022. This is likely due to its widespread availability—the fuel is available at more than 4,200 public fueling stations across 44 states, according to DOE—and because it’s compatible with many light-duty vehicle engines straight from the factory. While the most produced and most consumed alternative fuel, ethanol is also used in nearly all gasoline sold in the U.S., according to the EIA, which contributes to its consumption beyond the strict use of E10, E15, and E85.

The price of ethanol fuel is an aspect that could make it more tempting for fleet owners, as it is generally less expensive than 100% gasoline fuel. From 2022 to 2024, E15 consumers saved an average of 10 to 30 cents per gallon of the ethanol blend compared to 100% gasoline, according to Growth Energy. As for E85, its average price from October 1 to October 15, 2024, was $2.74 per gallon compared to gasoline’s average cost of $3.25 per gallon, according to DOE.

However, its lower cost doesn’t necessarily make it a more cost-effective option. Because a gasoline engine’s performance is most optimal using gasoline, according to DOE, ethanol consumers typically experience fewer miles per gallon of ethanol-blend fuel than with gasoline. Another reason ethanol is considered less efficient than gasoline is because of the energy content in its composition. EIA states that “the energy content of ethanol is about 33% less than pure gasoline” and that “fuel economy may decrease by about 3% when using E10” compared to 100% gasoline.

Ethanol is the most popular alternative fuel, but it is difficult to pinpoint how many fleets use it. EIA’s latest data on ethanol consumption within fleets is nearly a decade old and includes only data from federal and state government fleets, fuel provider fleets, and transit agency fleets.

In 2017, these fleets employed nearly 400,000 flex fuel vehicles and consumed nearly 28,000 “gasoline equivalent” gallons of E85, according to EIA.

What is natural gas?

While also considered a fossil fuel, natural gas is another alternative fuel choice that burns cleaner than traditional fuels while offering a similar performance. There are two types of natural gas fuels: compressed natural gas, or CNG, and liquefied natural gas, or LNG.

When combusted in a vehicle engine, CNG and LNG produce harmful tailpipe emissions such as hydrocarbons, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. However, the emissions from a natural gas engine are much more easily controlled through advancements in technology, according to DOE, compared to their gasoline and diesel counterparts—the latter requiring complicated diesel particulate filters.

Further, the DOE states: “NGVs with ultra-low NOx engines can produce near-zero NOx emissions, which meets the California Air Resources Board’s optional near-zero emission standard of 0.02 [g/bhp-hr] NOx.”

CNG is created by compressing natural gas to “less than 1% of its original volume at standard atmospheric pressure,” according to Shipley Energy. CNG fuel is stored in gaseous tanks onboard a vehicle.

Compressed natural gas offers performance that’s similar to traditional fuels in terms of acceleration, cruise speed, and horsepower. Yet it’s a bit less efficient than traditional gasoline and diesel fuel due to its decreased density, therefore requiring more CNG fuel to travel the same distance with gasoline or diesel. Nonetheless, DOE recommends its use in high-mileage applications in regions with ample CNG fueling locations.

On the other hand, LNG is nearly as efficient as gasoline or diesel in terms of performance and range, and according to Cummins, one tank of LNG allows a vehicle to travel more distance than one tank of CNG, which makes LNG a better option for long-haul applications. But while it’s more efficient, its use is less widespread due its complexity.

LNG “is created by purifying natural gas and then cooling it to negative-260 degrees Fahrenheit so that it turns into a liquid,” according to Shipley Energy. And keeping it cooled to this temperature is imperative for its transport and use, requiring LNG fueling stations to employ cryogenic equipment. Therefore, as of 2023, the U.S. has only about 50 LNG fueling stations compared to CNG’s 700-plus, according to DOE.

A downside to fueling with either CNG or LNG is that it requires a specific powertrain. These CNG and LNG-specific powertrains can be purchased directly from the factory—Cummins offers a natural gas engine for heavy-duty applications—or fleet owners can convert existing gasoline and diesel engines for light- and medium-duty vehicles. This conversion can be costly for fleets, from $3,000 for smaller, lighter vehicles to $60,000 for larger vehicles, according to Shipley Energy.

Along with costs to convert existing engines, fleet owners that hope to install natural gas infrastructure on-site will find additional infrastructure costs, as well.

What is propane?

Liquefied petroleum gas, also known as LPG and propane autogas, is a byproduct of natural gas and crude oil processing and refining. It is an odorless, colorless liquid stored in tanks under pressure. Once that pressure is released, “the liquid propane vaporizes and turns into gas that is used in combustion” engines, according to DOE.

Across the globe, propane is the third most-used fuel in transportation, but in the U.S., propane is used in anywhere from 60,000 to 270,000 vehicles, according to various sources.

The use of propane autogas is common among school buses, with more than 22,000 propane school buses in use across 49 states, according to the Propane Education and Research Council.

Using propane as a fuel requires a specific engine. While no OEMs offer a propane-powered vehicle from the factory, both Ford and General Motors offer prep packages for an aftermarket propane conversion.

Much like the other alternative fuels mentioned, propane autogas is less efficient than gasoline and diesel, with DOE stating that one gallon of the fuel provides 27% less energy than one gallon of gasoline.

However, propane-powered vehicles are easier to maintain because of their clean burn, and “low carbon and low contamination characteristics may result in longer engine life,” DOE states.

Fleets that choose to operate propane-powered vehicles might find it easier to fuel them using on-site fueling infrastructure. Unlike the cost and length of time associated with building infrastructure for other alternative forms of energy, such as electric vehicle charging infrastructure, the buildout of propane autogas infrastructure is simpler.

In exchange for a fuel supply contract, propane fuel suppliers will often lease the tank, pump, and dispensing equipment necessary for fleets to fuel on-site, DOE states. This leaves the fleet responsible for additional costs, such as the concrete pad for the equipment and an electrical line to supply any electrical needs to the equipment.

What is hydrogen fuel?

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and on earth, it is found in solid, liquid, and gaseous forms via compounds of other elements, such as water, ammonia, table sugar, hydrogen peroxide, and more, according to Jefferson Lab Resources.

Combined with liquid oxygen, hydrogen becomes LH2, a kerosene fit to fuel rockets, the Mars Society of Canada states. Hydrogen can also fuel on-road vehicles—and cleanly, emitting only water vapor and warm air.

There are hydrogen-powered vehicles on the road today, both with hydrogen fuel cell electric powertrains and hydrogen internal combustion engines. But widespread adoption of hydrogen-fueled vehicles has been hampered by its production and infrastructure development.

While hydrogen is the most abundant element, it must be isolated from element compounds and then converted to useful energy. It takes more energy to isolate hydrogen than hydrogen produces, according to EIA, but because hydrogen is such an energized element with a clean burn, there is a push to see it become a widely used fuel.

Hydrogen produces enough energy that it would take one gallon of gasoline to produce the same amount of energy as a quarter gallon of hydrogen, according to DOE, or more specifically, the “energy in 2.2 lb. of hydrogen gas is about the same as the energy in 1 gallon (6.2 lb.) of gasoline.”

Hydrogen fuel is compressed into a gas and stored in tanks onboard a vehicle. Tanks for hydrogen internal combustion engines can fuel in 5 to 10 minutes, whereas it takes 10 to 15 minutes to fill tanks for hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles. Tanks are refilled in private and public fueling stations, of which there are few, with most concentrated in California.

There are 54 public FCEV refueling stations currently open in California, with 20 more in “various stages of planning,” according to DOE, serving 15,000 FCEVs. There is also one public FCEC refueling station in Hawaii.

Hydrogen has failed to gain widespread adoption for multiple reasons. The main reason is cost. Hydrogen has high production and transport costs, which trickle down to the consumer. Hydrogen fuel is sold in kilograms, and Carbon Credits lists 1 kg of hydrogen fuel to cost from $5 to $16, yet S&P reported hydrogen prices for light-duty vehicles rose up to $36 per kilogram due to disruptions in supply throughout 2024. While 1 kg of hydrogen equals 2.8 kg of gasoline, this price difference is enough to scare most consumers and fleets from hydrogen-powered vehicles.

Also contributing to hydrogen’s hefty price tag could be the fact that the industry has failed to decide which form of hydrogen to produce and transport more broadly. Hydrogen is transported and stored in two ways: liquid or gas. And each method has different requirements. FleetOwner dives into this much further here.

Hydrogen as a vehicle fuel might still require several years of development before it takes off in the market, and the federal government has set aside a few billion dollars to see it through.

See also: Can hydrogen actually work for trucking operations?

What is biodiesel?

Made from used vegetable oils, animal fats, and recycled restaurant grease, biodiesel is a more sustainable alternative to diesel fuel. Just as ethanol is mixed with gasoline to create ethanol blended fuels, biodiesel is often mixed with petroleum diesel, according to DOE.

Also, as with ethanol blends, biodiesel is named according to its percentage of biodiesel versus petroleum diesel. Blends with up to 5% biodiesel and 95% petroleum diesel are called B5. Blends with 6% to 20% biodiesel with petroleum diesel making up the remainder are B20.

Fleet owners and drivers might already be using B5 in their vehicles today without knowing it, as the American Society for Testing and Materials International, the authority for specifying diesel fuel, doesn’t require that B5 fuels be labeled explicitly at the pump, DOE states. B20, on the other hand, must be labeled. However, B20 is compatible with most light- and medium-duty engines, performing similarly to 100% or B5 diesel.

It’s worth noting that blends of 20% biodiesel and 80% petroleum diesel will offer 1% to 2% less efficiency than pure diesel, and blends with a higher percentage of biodiesel will have even less efficiency.

While biodiesel blends are a more sustainable fuel derived from vegetable oils and other resources, DOE states they produce a similar amount of air-quality emissions as petroleum diesel. However, a higher blend of biodiesel produces fewer greenhouse emissions. For example, a B20 fuel will produce about 20% fewer greenhouse gases than 100% petroleum diesel.

Biodiesel blends also come with a cost difference. B20 can cost from 3 cents to 40 cents more than wholesale petroleum diesel, according to Shipley Energy. However, fleets that use this sustainable fuel may qualify for tax credits, which could offset any additional price paid at the pump.

What is renewable diesel?

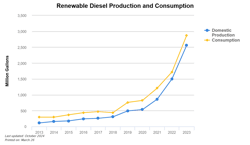

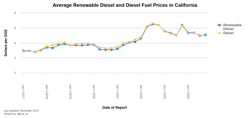

Similar to biodiesel, renewable diesel is made from animal fats and vegetable oils, but unlike biodiesel, renewable diesel is processed to be chemically identical to petroleum diesel, DOE states. Renewable diesel is considered a drop-in fuel, meaning it can be used to power any diesel vehicles immediately—no modifications necessary.

There are multiple ways to produce renewable diesel, and new production plants are growing (see the graph below). While most facilities are located in West Coast states, there are renewable diesel production plants in Kansas, North Dakota, and Oklahoma.

EIA states that renewable diesel can even be blended, transported, and co-processed with petroleum diesel due to its equivalent chemical makeup. The sustainable fuel can also be transported in existing petroleum diesel pipelines, negating the need to build additional infrastructure. Further, existing diesel refineries can be converted into renewable diesel production facilities quite easily with little associated cost, EIA states.

Renewable diesel is made from sustainable sources and also offers environmental benefits over petroleum diesel. DOE states that one study indicated that renewable diesel produces less carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxide than petroleum diesel, and it “reduces carbon intensity on average by 65% when compared with petroleum diesel.”

What is renewable natural gas?

Another drop-in fuel, renewable natural gas can power conventional natural-gas engines, both CNG and LNG.

A biogas produced from the decomposition of organic matter, renewable natural gas undergoes a “cleaning” process that removes any non-methane elements, according to DOE. This process “involves the removal of water, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and other trace elements,” DOE states.

Renewable natural gas can come from landfills, livestock operations, and wastewater treatment facilities. According to DOE, biogas produced from landfills is often used to produce electricity, whereas biogas from livestock operations and wastewater treatment facilities can be used to power vehicles. However, in 2023, there were roughly 470 anaerobic digester systems on commercial livestock farms that produced renewable natural gas used to produce electricity, and DOE lists just two farms that produce renewable natural gas to power vehicles.

The National Association of Clean Water Agencies released a study estimating that renewable natural gas derived from wastewater treatment plants could produce enough energy to cover 12% of the nation’s electricity needs, but of the more than 16,000 wastewater treatment plants in the U.S., only about 1,200 of them are producing renewable natural gas.

While these numbers appear low, Coherent Market Insights predicts the market for the biogas to grow by more than $10 billion by 2032.

About the Author

Jade Brasher

Senior Editor Jade Brasher has covered vocational trucking and fleets since 2018. A graduate of The University of Alabama with a degree in journalism, Jade enjoys telling stories about the people behind the wheel and the intricate processes of the ever-evolving trucking industry.