To help prepare the transportation industry for the transformative, zero-emission-centric decades ahead, The North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) has released an in-depth guidance report called "Making Sense of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Tractors."

The findings are available in an 11-page executive summary for a macro view, while fleets and stakeholders further along in their zero-emission journey can develop a more granular strategy through the full 143-page report, which includes 235 references and 102 figures to help distill the cascades of data flowing throughout the study.

“It could have been 10 times as much if we wanted to include everything,” confessed Mike Roeth, NACFE executive director, whose organization had previously released guidance and confidence reports on pure battery-electric trucks, tires, aerodynamics, and autonomous vehicles.

The authors, which included members of NACFE and the Rocky Mountain Institute, began the project with a healthy dose of skepticism on how commercial vehicles could leverage hydrogen fuel cells to eliminate emissions while still turning a profit. Key advantages include hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles’ extended range over direct battery-electric vehicles, as well as the near-unlimited supply of its fuel source — hydrogen. By the end, they found the advantages afforded by the powertrain will be worth the challenges ahead as the technology attempts to reach maturation. NACFE projects that will happen sometime in the 2030s.

Getting to that point will be no easy task, despite several decades of research and understanding into hydrogen propulsion.

“The costs of hydrogen, vehicles, and hydrogen production all must come down significantly to make hydrogen economically competitive with alternatives,” Roeth said. The report noted “an eight-fold reduction in hydrogen is possible” if enough dominoes fall the right way.

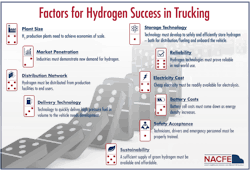

The below chart illustrates those factors:

One such domino that seems to be teetering is electrolyzer technology, which converts electricity to hydrogen, the reverse of how the fuel cell on the truck works.

“They're starting to become much, much more efficient,” said Patrick Molloy, senior analyst at the Rocky Mountain Institute, who added, “much larger volumes of renewable energy [are] starting to be available.”

Right now the technology is far more inefficient than battery-electric. A Volkswagen study referenced showed wheel-to-well, HFCEV is 30% to BEV’s 76% overall efficiency.

“Making electricity to electrolyze hydrogen which is then used in fuel cells to power vehicles is not as efficient as making electricity and using it to power vehicles directly in the first place,” explained Clean Technica author Steve Hanley in NACFE's report. “Every time energy gets converted from one form to another, there are losses. The more transformations there are, the more losses occur.”

Hydrogen does have the best energy density, though it also carries the heaviest cost. Citing April 2020 national average retail fuel prices (per gasoline gallon equivalent), NACFE found that hydrogen cost nearly eight times more than diesel (Hydrogen GGE: $15.95 vs. diesel at $2.33). Furthermore, how to develop and fund a network of fueling stations and how to deliver the hydrogen (generated onsite via electrolyzers or delivered as a liquid) remain looming questions.

“Industry advocates and researchers are confident that these costs will be reduced through scale and innovation over time,” Roeth remarked.

The U.S. Department of Energy is among the confident stakeholders, quoted in the report as believing: “Hydrogen is part of a comprehensive energy portfolio that can enable energy security and resiliency and provide economic value and environmental benefits for diverse applications across multiple sectors. Hydrogen can be derived from a variety of domestically available primary sources, including renewables; fossil fuels with carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS); and nuclear power.”

There is an unofficial color coding to help understand these sources:

The report said that steam method reformation (SMR), or using natural gas to make the hydrogen, comprises 95% of current production. At the onset of the electric revolution, every color of this rainbow will be needed, as transportation draws only 1% of the U.S. grid’s total electrical output, according to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. In the future, that demand could increase by 800%.

“The argument that hydrogen and electricity are two different horses is really kind of bogus,” offered Rick Mihelic, NACFE’s director of emerging technologies and study team manager. “Because ultimately, electrolysis requires electricity and to create hydrogen, you're going to need electricity – a lot of electricity. And if you want to ramp up hydrogen use for transportation, you're going to have to concurrently ramp up electricity generation.”

While for now, that may include electricity derived from fossil fuels, Mihelic said, “Eventually there's one winner. But that could be quite seriously many, many decades from now.”

Mihelic did point out FCETs have an edge on BEVs in regards to charging time. “Although battery-electric rapid charging is going to surprise people when they come out with 1MW- and 2MW-level chargers, it's still probably going to be lagging the term time that a hydrogen refilling will take.”

The guidance report also includes various industry voices who offer insights into their section of the giant puzzle.

“While hydrogen fuel cell technology is very promising, we know that widespread adoption will take time,” stated Amy Davis, president of New Power Business, Cummins, in the report. “Many factors will influence this, including emissions regulations, infrastructure, hydrogen availability and total costs of ownership. Buses and trains will likely be some of the first applications to transition to hydrogen, with the Hydrogen Council predicting that heavy-duty trucks will fall further out on the curve with about 2.5% of hydrogen adoption in 2030.”

To get to that modest slice of the pie, truck original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and suppliers have already begun to partner up to reduce the initial cost of innovation and production scaling.

This includes Kenworth and Toyota, Daimler Trucks and Volvo Trucks, and Cummins and Navistar. Toyota Motors North America and Hino could be first on the road next year with a fuel cell version of the Hino XL Class 8 truck.

“Not only are they a good thing, I think they're absolutely necessary if we're going to push this technology through into commercialization,” said Kevin Otto, NACFE's electrification technical lead, of the recent spate of alliances. “Because without those partnerships, none of the individual companies can necessarily support the kind of investment that's necessary to make all that happen.”

Along those lines, one of NACFE’s key recommendations is for stakeholders to remember: “Fleet investment in new fuel cell electric and battery electric vehicles requires vehicles. The debate on infrastructure is irrelevant if there is no demand.”

And here are NACFE’s final conclusions:

• Hydrogen fuel cell trucks are just starting to see real-world use and their adoption is being driven by regional or national considerations that are much bigger than what exists for trucking fleets.

• Battery-electric trucks should be the baseline for HFCEV comparisons, rather than any internal combustion engine alternative.

• As for all alternatives, fleets should optimize the specifications of HFCEVs for the job they should perform while expecting that the trade cycles will lengthen.

• The future acceleration of HFCEVs is likely not about the vehicles or the fueling but more about the creation and distribution of the hydrogen itself.

• Finally, the potential for autonomous fuel cell trucks to operate 24-hours a day adds significant opportunity for making sense of capital and operational investment in hydrogen.