Demonstration proves fleet electrification is possible—but there’s still a way to go

The North American Council for Freight Efficiency recorded the operations of fleets running electric commercial vehicles for three weeks in the fall of 2023. The event, Run on Less-Electric Depot, documented the operation of 22 battery-electric vehicles from 10 depots in Class 2 to Class 8. The purpose of RoL-E Depot was to demonstrate the efficacy of BEVs in large numbers for commercial applications. Using the information from the event, NACFE released a report on scaling EVs for fleet-wide operations.

Highlights of the report included perceived expectations and perceived EV requirements versus real-world operations and EV needs, the importance of reliable partnerships, and real-world data that can be used to spur EV adoption among fleets.

EV charging in the real world

“There is a need for information at multiple levels by multiple users, and there's a tendency to oversimplify the mathematics,” Rick Mihelic, lead author and director of emerging technologies at NACFE, said during a media webinar.

The example Mihelic gave was in the oversimplification of EV charging needs. For instance, if a fleet plans to use one EV with a 100-kW battery and wants to charge the vehicle to 100% once per day each day, the fleet leaders will outline this need to the fleet’s utility company. If fleet leaders decide that the battery should be charged within an hour, that places additional requirements on the utility to be able to handle the electricity output required for fast charging.

The utility uses that "worst-case" assumption to design “the pipeline that gets all the energy to the facility,” Mihelic said. “All the costs and the lead time on ordering components are all based on that fundamental assumption that it's 100 kWh of charging every night for an hour."

See also: What goes into planning an electric truck charging station?

In real-world operations, however, data from RoL-E Depot revealed that many EVs in fleet operations returned to base with 50% or less of the battery used throughout the day, Mihelic explained. This means the electricity required to charge the EV would be half of what was expected or planned.

In other cases, EV operators will bring the vehicle back to the depot to charge during their lunch break, causing facilities to have “more than one charging event during the day,” which can decrease the facility’s demand for energy, Mihelic stated.

Additionally, not every vehicle will require fast charging. Vehicles that return to base each night can charge 10 to 12 hours overnight, which helps decrease energy demand and save on electricity charges.

Another observation made from RoL-E Depot was that the battery packs in EVs “love charging” between 20 and 80 or 85%. “They charge very quickly at that level, and then the slower charge is above that,” Mihelic said.

Fleets have found that they can charge these vehicles up to 85% quickly, and “perhaps that's all they need to do."

All these real-world findings indicate how easy it would be for a fleet to install more infrastructure than necessary.

“You may have put in a 75-kWh charger and find out that you're only using ... 5 kW level charging over a 10- or 12-hour period,” Mihelic said. “So there are huge ramifications to misinformation about the charging and using the worst case as the foundation for planning.”

See also: Run on Less shows how depots can electrify today

RoL-E Depot shows partnerships are key to electrification

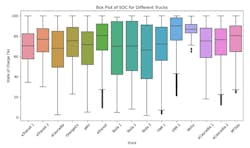

The electric vehicles observed in the report ran routes in urban and regional delivery. According to RoL data, the average state of charge of the battery in each EV in operation for the demonstration was above 60%.

In its executive summary, NACFE drew the comparison between “fueling” BEVs and fossil-fueled vehicles in delivery applications. When calculating the estimated energy consumption of a BEV, NACFE explains that using data solely from the energy consumed by a fossil-fueled vehicle is insufficient because of the way the energy is purchased.

“Depots do not pay for electricity based on vehicle kWh usage; they pay based on the total power delivered to the site,” the NACFE executive summary states. “Those costs may be fixed or variable depending on the time of day. The power levels include all the losses between the meter and the vehicle. There is a danger in estimating power demand based on vehicle data as this inherently does not include actual losses from the meter to the charger and from the charger to the vehicle.”

NACFE believes the nature of electricity consumption creates an opportunity for fleets to work together on common EV depots. This approach “could lead to partnerships in which two or more companies combine charging use to maximize charger asset utilization.”

See also: Scaling charging infrastructure: Where to begin

The RoL demonstration, along with most EV depot success stories, also highlighted the importance of teamwork and partnerships. NACFE’s report states: “Creating a BEV depot is a team effort involving the truck OEM, the charger manufacturer, the utility, the site management team, and multiple other groups related to permitting.”

The magnitude of communication required between these partners often leaves room for misinformation or lack of information altogether, leading planners to “default to worst-case values in the absence of real data,” the report states.

This misinformation or failure to communicate can lead to problems such as delays, building more infrastructure than needed, unnecessary costs, and more. Additionally, the report states that fleet managers involved in the RoL demonstration stressed the need to begin planning early and build a team of reliable partners.

Demonstration findings

While EV growth is taking place nationwide, RoL-E Depot proved there is still progress to be made. NACFE outlined four takeaways from the demonstration.

Infrastructure is needed now—at depots, but especially along major freight corridors in the U.S. NACFE’s report states this can be solved through fleet company partnerships, combining charging use for maximum charger utilization. Utilities should also give fleets realistic timelines for charging infrastructure development, and in that same vein, fleets should understand that the planning process for a utility can be from six months to several years.

See also: Where alt-fuel infrastructure stands today: EV charging infrastructure

Another improvement NACFE outlined to accelerate the adoption of EVs among fleets would be to decrease the weight and the cost of heavy-duty EV tractors. While light- and medium-duty EVs are proving their worth with fleets, NACFE reports that many fleets still cannot make the TCO case for BEVs. Further, more information is needed surrounding the residual value of BEVs, charging infrastructure costs, energy costs, and more.

Third, NACFE concludes that more realistic data on key performance metrics is needed for more rapid EV adoption. Operating a BEV includes more than just the vehicle. It includes the charger, charger network, teamwork with the utility, and more. Data should be collected to reflect realistic operation cycles instead of working off “worst-case” scenarios.

Finally, and on a positive note, NACFE concludes that, through the learnings of its RoL-E Depot, electric vans, trucks, and heavy-duty tractors are on the road and performing well in many duty cycles. This proves that despite the many challenges faced when shifting operations from fossil-fueled to BEV, it truly can be done.

About the Author

Jade Brasher

Senior Editor Jade Brasher has covered vocational trucking and fleets since 2018. A graduate of The University of Alabama with a degree in journalism, Jade enjoys telling stories about the people behind the wheel and the intricate processes of the ever-evolving trucking industry.