Editor's note: This is part one of a two-part series on how safety and TCO can improve with next-gen braking systems.

Vehicles in the U.S. traveled 13% fewer miles in 2020 than 2019, yet road fatalities increased by 8% to 42,060 — the highest in 13 years, according to the National Safety Council (NSC).

“The number of roadway fatalities is alarming,” said NSC president and CEO Elaine Martin. “But the death rate is even more troubling. The U.S. experienced a staggering 24% increase in the rate of deaths per 100 million vehicle miles on our roadways last year. This is the highest year-over-year increase we have reported since the council began calculating it nearly a century ago.”

An additional 3 million people are injured in crashes annually, costing the U.S. $460 billion. Martin acknowledged “it's too early to ascertain complete causation,” though roadway systems ill-suited for modern driver errors was considered a factor.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the mental and emotional stress it created likely impacted driver behavior as well. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found in the early stages of the pandemic lockdowns: “Of the drivers who remained on the roads, some engaged in riskier behavior, including speeding, failing to wear seat belts, and driving under the influence of alcohol or other drugs.”

In a study conducted by five trauma centers between mid-March to mid-July, nearly two out of every three drivers brought in after a serious or fatal crash tested positive for alcohol, marijuana, opioids, or other drugs. After mid-March, positive opioid tests nearly doubled, and marijuana use rose about 50%.

There are myriad other reasons why the roads have become more dangerous, such as heavy speeding (which fleets did 20% more frequently last April, according to Samsara). But the bottom line is that the roads are becoming increasingly unpredictable, and fleets need to upgrade their defensive strategy.

At some point this will likely include the adoption of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) such as collision mitigation and automatic emergency braking. According to the Rand Corporation’s Road to Zero report, this technology would save 10,000 lives annually if the current array of ADAS were available on every vehicle. Daimler Trucks’ Detroit Assurance 5.0, for instance, can sense pedestrians using radar and camera sensors, and it will partially or fully activate emergency braking if the driver does not respond to visual and audio alerts.

But fleets don’t necessarily focus entirely on high-tech solutions to improve their safety. They can start by simply re-evaluating how trucks stop. This includes foundation brakes, the engine brake, and, for the new wave of electrified trucks, regenerative braking.

If a fleet is to put its drivers, equipment, and cargo in the safest position possible, it ought to have the best braking systems and technology financially feasible. Luckily, many modern braking advances reduce stopping distance and retain or improve upon legacy systems’ total cost of ownership, allowing fleets to break even on cost while vastly improving stopping power.

And after safety performance, the TCO of a braking system is a very real concern and limiting factor for fleets. Like tires, brakes accrue more wear and tear the more they are used. Maintaining and replacing brakes are top costs for many fleets.

This varies greatly by duty cycle and location. A refuse truck that stops at every house in a neighborhood puts its brakes through quite a workout every day, while on-highway trucks often may need only to tap the brakes to adjust speed due to traffic. A long-haul truck that inches through downtown Chicago congestion or rides the brakes down the Rocky Mountain highs of Interstate-70 in Colorado will need brake lining replaced far more often than a regional hauler in Texas.

Fleets with higher brake wear will inevitably have shorter replacement intervals and the downtime that comes with it. But whatever the fleet, revisiting what type of brakes are being used and how drivers and maintenance technicians are trained to operate and work on them will yield better safety scores and manageable maintenance costs.

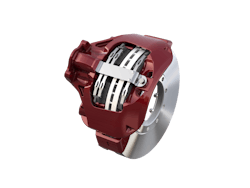

Air disc brakes

In the past decade, due to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration enacting shorter stopping distance regulations (FMVSS 121), brake manufacturers have rolled out new materials and components to improve braking system performance. Two-axle tractors and 6x4 tractors above the 59,600-lb. gross vehicle weight rating threshold must stop within 250 ft. when traveling 60 mph and pulling a trailer. Previously, it was 355 ft. This led to air disc brakes (ADBs) finally gaining a foothold in North America.

Along with electronic braking systems (EBS), air disc brakes have been common on European trucks for two decades. According to Swedish brake maker Haldex, the take rate for EBS/ADB configurations was 70% in 2000. That number exceeds 80% now.

In North America, the take rate is hovering just below 50%, according to Meritor – up from 15% in 2015. Meritor’s recently launched EX+LS ADBs are standard on model year 2022 Freightliner Cascadias.

The lightweight EX+LS also meets the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s 2025 reduced copper standards, enacted to keep copper out of the water supply.

Meritor Director of Engineering Joseph Kay also noted these brakes are compatible with trailers that have drum brakes and won’t “shift that wear balance between the tractor and trailer.”

ADBs, which comprise a wheel hub assembly, a brake caliper assembly, and a disc rotor, have several advantages over S-cam drum brakes.The first is performance. Air disc brakes have demonstrated the ability to stop a 6x4 truck going 60 mph in 200 ft., whereas a drum brake would take 225 ft., according to Bendix Commercial Vehicle Systems tests.

Pitt Ohio, a fleet of 1,400 power units, began the transition to ADBs two years ago, though not all units have it yet. Jeff Mercadante, vice president of safety, recalled seeing how the Bendix ADB22X air disc brakes performed on a test track, where a truck with ADB going 55 mph stopped 15 ft. shorter than one with drum brakes. “Fifteen feet is the length of a car,” Mercadante said. “When you get up to 70 mph, you’re talking closer to 50 to 60 ft.”

So far, Pitt Ohio has seen the improvements bear out on the road. “Our rear-end collisions came down because of air disc brakes and the [Bendix Wingman Fusion’s] collision avoidance system on the front,” Mercadante explained.

The Wingman Fusion system will recognize if the truck is following too close to the vehicle ahead, alerting the driver when the vehicle is half a second from collision. If the driver does not slow down, the Bendix Electronic Stability Platform will take control of the brakes. It’s important to tell operators the faster the truck is going, the less reaction time there is.

“Generally speaking, the system will mitigate approximately 70% of the number of rear-end accidents and an additional 70% of the severity of the ones left over,” explained T.J. Thomas, Bendix director of marketing and customer solutions for controls group.

Improving on that safety metric started in the training room.

“We had Bendix trainers go in our facilities and educate the technicians on how they worked and how to maintain them and how to inspect them,” said Taki Darakos, Pitt Ohio’s vice president of vehicle maintenance and fleet services. This was pre-pandemic, so it was a more hands-on experience. Once drivers started using them, feedback was highly positive for the “automotive feel” of the new brakes and noticeably improved stopping distance.

Pitt Ohio will continue to transition its heavy-duty fleet with ADBs as it refreshes with new trucks. While replacing the drums on trailers is a consideration, it’s not as vital as the trailer brake wear items at Pitt Ohio require less frequent changeouts.

“We have a couple thousand trailers and an upgrade to air disc brakes that takes time and money, and then you're sacrificing something somewhere else,” Darakos said.

Jaded by fading

Another advantage is how ADBs retain consistent performance despite periods of extended use, while drum brakes are susceptible to heat built up from friction.

“A drum brake goes through a phenomenon called fading,” explained Keith McComsey, director of the Air Disc Brake Product Group at Bendix Commercial Vehicle Systems. Brake fade can occur when the drum heats up to a point where it starts to expand away from the friction material, so stopping performance gets worse. It’ll take a longer pushrod stroke in order for the brake to come in contact with the drum frictional surface.

“With air disc brakes, you basically have two pads that are squeezing up against the disc, and as that disc heats up, it actually thermally expands towards the friction, so you don't have the same phenomenon,” McComsey explained.

Part two explores ways in which air disc brakes can drive new TCO benefits.

About the Author

John Hitch

Editor

John Hitch is the editor-in-chief of Fleet Maintenance, providing maintenance management and technicians with the the latest information on the tools and strategies to keep their fleets' commercial vehicles moving. He is based out of Cleveland, Ohio, and was previously senior editor for FleetOwner. He previously wrote about manufacturing and advanced technology for IndustryWeek and New Equipment Digest.