There are as many different truck specifications as there are commercial vehicle fleets in operation today.

Each business has its own needs, options, budget, and driver preferences—and each truck has hundreds of components that can be fine-tuned for that business.

Spec’ing a Class 8 truck means diving into all the gritty details of both fleet needs and truck components.

This is part of FleetOwner's Fleets Explained, a Trucking 101 series to break down aspects of the trucking and fleet management industries. You can read more from the series, launched in May 2024, at fleetowner.com/fleets-explained. To submit topic ideas, clarifications, and corrections, email [email protected].

Identify business needs: Three ‘C’s

Choosing the right truck means first defining what “right” means. Each fleet has its own definition of “right,” and shaping that definition is the first step in spec’ing trucks.

Three factors can help define “right” for your operation: duty cycle, compliance, and communication.

Cycle

If a fleet manager goes to a dealer looking for new equipment, the first question they will hear is “what is your duty cycle?”

Truck specifications depend entirely on the application and how the truck will be used. When it comes to duty cycle, the most important factors to consider are weight, location, speed, and annual mileage.

Compliance

Fleet vehicles must comply with state and federal laws. This includes reporting and licensing across several agencies. If a carrier plans to haul hazardous materials, for example, its equipment must comply with laws that are specific to that application.

Most stock tractor-trailers from dealerships comply with existing laws, but highly customized equipment can easily run afoul of the law. Falling out of compliance has disastrous consequences, so spec’ing should always ensure compliance with the federal Department of Transportation’s agencies, state DOTs, and any other relevant groups.

Communication

Spec’ing is not just about components but also business relationships. Communication is one of the most critical steps in specifying the ideal truck. Choosing a truck’s configuration should involve dialogue with every party, from dealers to drivers.

Fleet managers should prepare well-thought-out questions about any relevant aspect of their operation before engaging stakeholders.

It is crucial to listen to the feedback from drivers and technicians, as they are the professionals who use this equipment the most. Did drivers experience problems with current or past vehicles, or have they reported dissatisfaction with in-cab amenities? Do technicians report specific components failing more often than expected, or do they find that a certain manufacturer makes repairs unnecessarily difficult?

Dealerships often have highly technical information about specific truck components, which can help decide whether a particular component fits a particular duty cycle.

Top considerations for finding the right truck

Trucks are complicated. Each component choice has implications for several essential aspects of its operation. Choosing a truck or component is more likely to be correct when it satisfies the factors below.

Fuel efficiency

Fuel is the biggest per-mile cost for commercial carriers besides driver pay. The right truck spec should be as fuel efficient as possible for its duty cycle. The truck’s powertrain, tires, and aerodynamics can maximize fuel efficiency.

Maintenance, life cycle

If a truck is in the shop, it is not making money. Fleets should aim to spec a truck for the greatest reliability and life cycle that falls within their equipment replacement schedule.

When spec’ing a new truck, the fleet’s previous vehicle maintenance records can identify areas of improvement. Repeat failures can mean that a component is under-spec’d.

Some OEMs, like Volvo, might also include upkeep packages or warranties to help maximize uptime and ensure their customers are satisfied.

Payload

The payload is one of the most essential parts of a duty cycle. It is important that the truck is equipped with a chassis and powertrain designed specifically for the type of freight it is hauling. A truck’s GVWR, payload capacity, and towing capacity are some of the variables that can determine whether it matches the duty cycle of a fleet.

Typical terrain

Terrain has major implications for truck operations. Highways and unpaved roads can require very different tires. Steep inclines might need greater torque to haul goods. The truck might need particularly high ground clearance for uneven terrain, or low clearance for special loading. The vehicle’s wheelbase or track might need to be more compact for urban maneuverability.

See also: Fleets Explained: What is a tank truck?

Cost

Cost is one of the most important factors in choosing a truck.

The right truck choice matches the fleet’s needs for the lowest reasonable price. Under-spec’ing a truck can lead to increased downtime and maintenance costs, but over-spec’ing a truck is often an immediate waste of money.

Fleets should consider the following:

- What are the upfront vehicle costs?

- Will cheaper specifications still satisfy the fleet’s standards?

- Will a cheaper option compromise safety?

- Can the company receive financing from lenders?

- How much will the asset’s value deteriorate over time?

- Will the truck order’s lead time work for the fleet’s needs?

Visual identity

As superficial as it may be, a truck’s look can be as important as efficiency when it comes to winning over clients.

Many trucks on the road today look worn, dirty, and are decorated with pictures of inappropriately dressed women. Many more trucks look sleek, clean, and are coordinated to match the carrier’s brand colors. Which fleet vehicle would a customer prefer to have in their yard, facing the public, potentially for several hours?

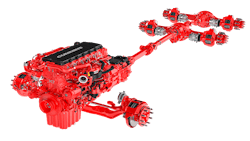

Key powertrain components

A commercial vehicle’s primary function is its ability to move goods from one place to another. Engines, gear trains, axles, brakes, and tires are the foundations of every fleet’s business.

Here are a few of the most important powertrain components when spec’ing a truck.

The engine

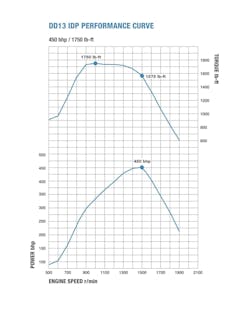

A typical internal combustion engine burns fuel to produce the energy that moves loads. The most important outputs of the engine are its torque (the force to pull a load) and its horsepower (energy and distance over time).

The engine can vary its output by burning fuel more quickly, measured as rotations per minute. A higher rpm tends to produce more horsepower and torque, but each engine has its sweet spot for the most efficient rpm.

Some of the most critical factors in spec’ing an engine are its power output, fuel efficiency, size, and reliability. Inefficient engine spec’ing can increase operating costs through unnecessary fuel consumption or engine wear.

Alternative powertrains introduce many more questions. Battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles use electric motors instead of combustion engines, and alternative fuel sources are often less efficient than diesel. These differences have impacts on the vehicle’s suitable duty cycles.

The transmission

The transmission uses a set of gears to better adjust the engine’s produced speed and torque. By adjusting a truck’s gearing in real time, the transmission can raise either the torque or horsepower. The transmission choice has implications for payload capacity, fuel efficiency, and ease of maintenance.

Automated gearboxes tend to be standard for today’s transmissions, but manuals can still be practical in very heavy applications. For most duty cycles, automated transmissions are the optimal choice to lengthen clutch life, improve fuel economy, and reduce driver strain.

Some key factors in choosing a transmission are torque, slow-speed maneuverability, forward speed, reverse speed, maximum grades, power takeoff compatibility, and maintenance needs.

Today’s transmissions work very closely with their engines. Manufacturers tend to sell these components together. When in doubt, fleets should choose engines and transmissions that were specifically designed to work together by an OEM’s engineers.

Axles

Another important factor is a vehicle’s axle makeup. This decides how the tractor supports a load’s weight and how the powertrain sends power to the wheels.

A vehicle’s gross axle weight rating has important regulatory implications. The right axle spec requires that the truck’s hauls never exceed its GAWR.

Axle configurations

There are many options in choosing how many axles the chassis has, how they receive power (powered axles), and which ones are used to steer (steering axles). These options comprise the axle configuration, also known as the chassis configuration.

The most common axle configuration terms used in over-the-road trucking are 6x4 and 6x2. These names describe the composition of powered axles and steering axles. A 6x4 configuration is the most traditional for trucks: A 6x4 chassis has six total wheels and four drive wheels (three total axles, with two drive axles). A 6x2 has six total wheels but only two drive wheels.

With more drive wheels, the 6x4 produces greater torque for hauling heavy loads or negotiating rough terrain. Compared against the 6x2, however, more drive axles mean greater rolling resistance, leading to worse fuel economy—about 2.5% less efficient than that of a 6x2.

The chassis axles not only determine performance but also have significant regulatory implications for weight compliance and registration. Other important factors include axle spacing/grouping, suspension articulation points, and lift axles: A carrier’s specific operations and jurisdiction will shape these choices.

Axle gear ratios

The axle ratio is an important factor in torque and fuel efficiency. The axle ratio refers to the gearing in a truck’s differential, which dictates how many driveshaft revolutions translate to wheel revolutions. Similar to transmission gearing, the differential’s gearing multiplies the torque applied to the wheels—but unlike the transmission, this gear ratio does not change.

An axle ratio of 2.79:1 provides less torque and greater fuel efficiency, while a ratio of 3.73:1 provides greater torque at the cost of speed and fuel efficiency. Lower ratios can be suitable for most on-highway loads below 80,000 lb. Steep terrain and heavy hauls may require higher axle ratios.

Tires

The truck’s tire choice has significant impact on its longevity, grip, fuel efficiency, speed, and maximum weight. These factors are determined by the tire’s material makeup, tread design, rolling resistance, dimensions, and more.

Different tire compositions suit specific seasons, geographies, road environments, costs, and repair frequencies.

Tires are also one of the more safety-critical components of a truck. Tire failures can cause disastrous accidents, so their reliability should be much more important than affordability.

Brakes

The most safety-critical parts of the truck are the brakes.

Trucks use either air brakes or hydraulic brakes. Most long-haul trucks use air brake systems—either disc brakes or drum brakes—which use compressed air to apply pressure to the brakes. Hydraulic brakes use hydraulic fluid to apply pressure. Air brakes are more popular and are easier to maintain, but they apply less power than hydraulic brakes.

Federal standards require brake systems to fully stop tractor-trailers in no more than 250 ft. when loaded to their GVWR at 60 mph.

Do your homework

These components are far from an exhaustive list. Even the components listed have many slight variations not mentioned here.

Other important parts of a truck can include its cabin interior, driver amenities, trailer, air system, fuel tanks, idle limiting, electrical systems, driver assistance tech, frame rating, telematics systems, and more.

As long as the fleet has a clear definition of what the “right” equipment entails, it will be able to navigate spec’ing across any other components.

About the Author

Jeremy Wolfe

Editor

Editor Jeremy Wolfe joined the FleetOwner team in February 2024. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point with majors in English and Philosophy. He previously served as Editor for Endeavor Business Media's Water Group publications.