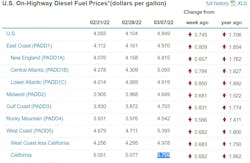

In the category of maybe some records aren’t meant to be broken, the cost of a gallon of diesel shot to a never-before-seen high this week as the U.S. average of trucking’s main fuel reached $4.849, rising 74.5 cents in one week mostly on market volatility over Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

By comparison, the week before on Feb. 28, diesel rose nearly 5 cents nationwide, averaging $4.104 per gallon in the U.S., when the effects of the Ukraine invasion were just starting to impact the worldwide market for crude oil. Based on the March 7 report from EIA, prices are sure to go even higher, however, as the administration of President Joe Biden announced March 8 that the U.S. would ban all imports of Russian oil as it heaped on penalties for the violence in Ukraine.

See also: Ukraine update: Understanding risks to U.S. trucking, transportation

Diesel prices on the East Coast of the U.S. and in California rose to crippling levels, based on the March 7 report.

Consumers are also bound to be hit in the wallet by the all-time-high fuel prices. The U.S. gasoline average surged 49.4 cents the week of March 7, rising above the $4-per-gallon level to $4.102.

In announcing the import ban on Russian oil, Biden said prices were bound to rise but cautioned the U.S. energy industry against “excessive price increases” and the exploiting of consumers, according to The Associated Press.

“We will not be part of subsidizing Putin’s war,” Biden declared, calling the new U.S. action a “powerful blow” against Russia’s ability to fund the ongoing offensive. He warned that Americans will see rising prices, saying, “Defending freedom is going to cost,” according to AP.

"Russian oil will no longer be accepted at U.S. ports," Biden added in his March 8 remarks at the White House.

See also: Oil markets volatile amid Russia's invasion of Ukraine

The ban is expected to be devastating to the Russian economy, which relies on oil and gas production for more than 40% of its revenue, Rystad Energy said.

Oil prices surged on the announcement, with the Brent benchmark jumping $5/bbl after the news broke, according to Oil & Gas Journal, a sister publication to FleetOwner.

Joining the U.S., the U.K. government announced a plan to phase out imports of Russian oil and petroleum products by the end of 2022. The European Union also unveiled a plan to wean itself off Russia's fossil fuels.

“Although the impact on U.S. supply may be limited, prices are soaring because the ban makes it more of a challenge to trade in Russian oil and more likely that other countries may follow suit. The oil market volatility is an inverse mirror image of the 2020 pandemic collapse, as compounding supply factors push prices higher,” said Bjørnar Tonhaugen, Head of Oil Markets at Rystad Energy.

The U.S. imports nearly 500,000 b/d of petroleum products from Russia, predominantly unfinished heavier oils, into its complex refineries. As imports from Russia will no longer be possible, refineries need to source their feedstocks elsewhere.

“The market, and U.S. buyers, already started to shun barrels from the Russian region immediately since the outbreak of the war, owing to swift implementation of financial sanctions, restricted commodity financing from lenders, or as a result of political decisions to opt away," Tonhaugen said.

“The 4.3 million b/d of ‘Western’ crude imports from Russia in January 2022 cannot be replaced by other sources of oil supply in a short period of time. Therefore, oil prices must rise to destroy sufficient demand and incentivize a supply response through higher activity, both of which will happen with a time lag of several months, to rebalance the market at a higher price,” he continued.

“How high oil prices will need to go depends primarily on how much and for how long the market will need to shun export barrels from Russia and whether other buyers, such as China, will step in to increase its purchases of oil from Russia.”

“OPEC+ holds approximately 4.0 million b/d in spare crude capacity, but there are few signs that the Middle East producers are opening the taps, at least not yet. With no additional OPEC+ response, the most significant potential oil supply shortage since the 1990 Gulf War (when oil prices doubled) could be upon us,” Tonhaugen said.

Where diesel goes, so may go consumer prices

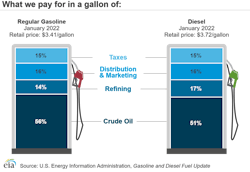

Skyrocketing diesel prices mean much more to the nation than the costs that truck drivers and fleets pay at a truck-stop pump.

Over the longer term, fleets can use fuel surcharges to defray some of the diesel-price shock. But when prices rise so quickly, as they've been doing in the past three weeks, trucking can't help but pass along some these costs to consumers.

Most products used in the U.S. are transported by vehicles with diesel engines—trucks and trains, according to the EIA.

“When the price of fuel rises quickly, our members take a significant hit to the bottom line,” Tiffany Wlazlowski Neuman, vice president, public affairs at NATSO, a national trade association representing America’s travel plazas and truck stops, told MarketWatch.

Neuman pointed out that if diesel prices climb to their record high, it would cost a truck driver $1,453.50 to buy 300 gallons to drive roughly 2,010 miles.

Trucking companies may attach a surcharge to their deliveries, and that surcharge may be “slow to get started and slow to end,” she said. "Ultimately, they are applied to every delivery and every item,” so the price of everything rises for U.S. consumers.

About the Author

Scott Achelpohl

Managing Editor

Scott Achelpohl is a former FleetOwner managing editor who wrote for the publication from 2021 to 2023. Since 2023, he has served as managing editor of Endeavor Business Media's Smart Industry, a FleetOwner affiliate.