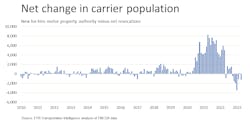

The tumbling freight spot market and historically high fuel prices are teaming up to push more small fleets out of the trucking industry—which is setting records in carrier departures this year, according to the latest federal data—amid the backdrop of a fits-and-start economy on the edge of recession.

This means many trucking companies—31,278 of them in the four months to start the year, this data shows—are folding up shop and leaving the industry. Or their operators are leasing their services to larger fleets. And more are filling seats as company drivers, easing the driver shortage.

Watching “revocations” of operating authorities with the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (how the U.S. government measures fleet expansion and contraction) also indicates how volatile the trucking business has been since COVID-19 transformed the industry.

This is apparent in another, longer-term trend interpreted from the FMCSA data: An industry exodus is most certainly underway right now, but the losses have many, many months to go before they wipe out the inflow of carriers—mostly one- and two-truck operators—that sought and got authorities from July 2020 into the first quarter of 2022, when spot rates were much more favorable, and diesel was a lot cheaper.

See also: April declines make May a crucial month for truckload freight, DAT says

Avery Vise, VP of trucking at industry data aggregator FTR Transportation Intelligence, is a leading authority on these trends in trucking, the comings and goings of freight-haulers, and what causes their businesses to flourish or flounder. The data and analysis Vise recently provided FleetOwner reveals more about the current freight landscape.

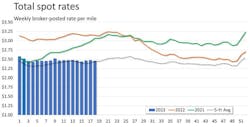

Of the more than 31,000 fleets that surrendered their operating authorities between January and April this year, 24,806 were one-truck outfits, according to Vise. That means 79% of these losses were borne by owner-operators, who entered in large numbers during better times two years ago but are fleeing now. Spot rates are down about 70 cents per mile from a year ago in trucking segments dry van, refrigerated (reefer), and flatbed. The good times, Vise remarked, "probably lasted longer than any of them anticipated—spot rates at the time seemed so attractive."

See also: More signs add to anxiety over rough freight economy

The Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association offered a similar perspective. "As COVID shut down jobs and stimulus money entered into the economy, demand increased for all kinds of goods. Trucking responded with record growth of new trucking businesses in response to that demand, which is now cooling off," read a May 12 statement by Norita Taylor, OOIDA's director of public relations.

"In short, there are too many trucks for the amount of freight in the market right now," OOIDA added. "We anticipate seeing more owner-operators lease their trucks onto other carriers until the freight cycle shifts upward again rather than stay under their own authorities."

'The raw numbers are high'

Vise also said, "Yes, the raw [FMCSA revocation] numbers are high, but not unexpected given the unprecedented scale of carrier creation during that two-year period."

The exodus so far this year is not limited to owner-operators and the smallest fleets, according to Vise. In the first four months of 2023, he observed that 42 carriers with 100 tractors or more lost or gave up their operating authorities compared to seven during the same period to start 2022. Mergers and acquisitions might explain some of the 2022 losses in this category, but the 2023 numbers are much more of a red flag that freight market conditions have degraded, he said.

The picture for 2023 so far isn't all negative, Vise added, and not nearly everybody is fleeing the market. In the first four months, 25,536 new for-hire trucking operations entered the market. Subtracting out the revocations during the same period, trucking lost 5,744 operations on a net basis, Vise noted.

"I believe that, had we not seen the steady relief in diesel prices that we've seen since they reached a record in June of last year, the level of failures actually would have been substantially higher," Vise said. "That almost unbroken period of fuel-price drops has helped soften the blow of lower spot rates, but the decline in spot rates is a bigger factor."

"Big change in spot rates has a far bigger effect on the health of a carrier than diesel prices," he observed. "My message is spot rates are done moderating. We're not likely to see any further decline. We probably have seen the bottom, certainly in refrigerated. Dry van may have bottomed out, and flatbed is still strong."

Is a bottom for the spot market in plain view?

Operators, load boards, and trucking stakeholders have been looking for light at the end of the tunnel for several months. Data from Vise's own FTR and load board operator Truckstop and the most recent analysis from another freight transportation data outfit, DAT Freight & Analytics, which runs its own load board, DAT One, hedge on the notion that a rebound in volumes and spot rates are imminent.

All still see, as the U.S. Bank Freight Payment Index did earlier in May, that volume still suffers and spot rates are trying to fight off their doldrums. Vise's FTR and Truckstop generally are more optimistic about this than DAT.

DAT's most recent analysis, a measurement of its Truckload Volume Index from April sent to FleetOwner on May 10, sees dry van and refrigerated off 15.5% and 16.3% from March, respectively, and down 12.3% and 12.5% year-over-year. Flatbed was down from March but 3.5% higher than April 2022.

See also: Another survey sees spot market 'close to turning a corner'

The money shouts, however, when viewed from the viewpoint of shrinking per-mile margins, especially compared to a year ago.

The same DAT index report also sees dry van spot rates averaging $2.06 per mile, down 10 cents from March and 71 cents per mile lower than April 2022. DAT's measure of spot refrigerated rates had them down 9 cents on average to $2.41 per mile from March 2023, or off 72 cents from last April. Even flatbed last month dipped 4 cents to $2.67 per mile and was 70 cents lower than last April, according to DAT.

Eric Crawford, VP and senior analyst at ACT Research, DAT and FTR's companion in the industry analysis space, added more depth to the inadequacy of current spots rates, noting that fleet average costs per mile have gone up in the last year by 5% while their revenue per mile has gone the opposite direction, slumping 15%. "We're looking at a cost per mile on average of about $2.93," he said, whereas DAT's best spot rate, for flatbed, sits at $2.67 per mile.

Crawford also conceded that a much larger percentage of fleets run dry vans, bringing the deficit of van's current spot rates into sharp focus because this affects most freight-haulers.

Chief of Analytics Ken Adamo added in DAT's May 10 email: "May will be pivotal for shippers, brokers, and carriers. After a challenging first four months of the year, we expect to see the effects of seasonality on freight volumes and rates. The question is how sustainable those effects will be."

"In our own forecasting," ACT's Crawford noted, "we're also calling a trough in spot rates [in May], but the other key thing that we think is going to help is" International Roadcheck 2023, which takes place this week, May 16-18, throughout the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The annual commercial vehicle inspection blitz usually takes a significant portion of total capacity off the road because of out-of-service violations, giving spot rates a shot (albeit temporary) in the arm.

There is a gulf between spot rates and fleets that are fortunate enough to run freight under contract, which has become a kind of safe haven. Fleets, mostly larger ones, with contracts to haul freight are doing better, even though U.S. average rates for contracted freight were lower in April compared to March, according to DAT. The spread in prices between contract and spot rose to near all-time highs last month: 62 cents per mile for dry van, 60 cents for reefer, and 66 cents for flatbeds.

Adamo called the spread between spot and contract rates "an indicator of where we're at in the freight cycle—the balance of bargaining power among shippers, brokers, and carriers." For the gap to close, two things need to happen, he said: "One, the supply of trucks on the spot market needs to diminish, which unfortunately means more carriers exiting the market. Two, there needs to be higher demand for trucks—in other words, shippers with more loads than they planned for."

"In 2016 and 2019, it was precisely the third week in May when the spot market entered a recovery phase after prolonged declines and stagnation," Adamo concluded. "Seasonality kicked in, and shippers needed more trucks to move fresh produce, construction materials, imports, and summer and back-to-school retail goods. If we see an uptick in demand before Memorial Day, it will be a welcome sign for owner-operators and small carriers as we head into the summer and fall."

FTR's outlook, in partnership with Truckstop, breaks the trends down by the week in the partners' Spot Market Insights. The May 8 report sees accelerating strength in spot rates for reefer carriage during the first week of May, an increase of nearly 12 cents in broker-posted rates in that segment. Dry van rates, however, for the week beginning May 1 showed that segment continues to slide. Flatbed also declined, according to the Truckstop/FTR report.

More longer-term perspective on fleet losses

Taken longer term to include the COVID period, other data overall since July 2020 is striking. Even with the loss of 9,796 carriers since October 2022, 113,598 more for-hire carriers have entered the market than have left since mid-2020. More than 70% of those consist of one truck, Vise's numbers show, so record numbers have departed, but many more owner-operators have stuck around.

And the vast majority of those new carriers since 2020 have been drivers who quit being leased owner-operators or company drivers and obtained their own authorities, Vise said. However, because larger carriers backfilled many of these jobs, the industry had a significant increase in the driver population, he said, which might be welcome news to people who monitor the overall industry driver shortage. FTR estimates that for-hire carriers of all sizes employ about 18% more drivers today than in March 2020—and truckload driver wages are up 18% over the past two years.

"The big question is what happens now," Vise concluded. "It appears that spot rates are bottoming out in the near term, and we will keep seeing lower diesel prices. If freight volume remains solid—and that's our outlook—we could start to see failures moderate and new entries stay high. That would essentially leave in place that shift of capacity from large carriers to small carriers that we saw from around mid-2020 to early 2022."