Like a precision marching band parading through the streets on New Year's Day, managing the miles between pickup and delivery is a study in choreography. It takes planning, timing, and, in trucking's case, a little bit of luck to make it work.

Take, for example, a trip from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to Providence, Rhode Island. Google Maps offers three obvious routes, ranging from 348 to 387 miles. Two possible routes cross the George Washington Bridge; one bypasses the GWB but is about 40 miles longer. Estimated travel times in perfect conditions range from 6:12 to 6:54.

Now factor in real-life traffic and time of day, and an eight-hour trip could easily become much longer. How can you plan for that?

Rishi Mehra, VP of commercial mapping and routing technology at Trimble, said fleets are focusing more on this problem as they try to keep their trucks moving and the drivers happy.

"Fleets are becoming more innovative in how they plan for drivers' break times, for example, and planning overnight parking in places where morning traffic, like crossing the George Washington Bridge, will pose problems," he said.

"We're trying to work backwards, factoring in the dwell times and traffic and parking to get them in a position where the driver is fully available to complete that delivery and start picking up another load."

Unpredictability

But traffic congestion is just one barrier to optimizing cost and efficiency in middle-mile operations. Factor in unpredictable dwell times at loading docks and possibly breakdowns, and the soup starts to look more like a stew.

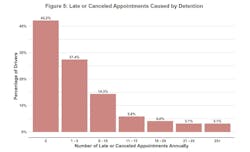

A recent American Transportation Research Institute report on truck driver detention costs illustrates the impact dwell time has on productivity. For example, the report noted that nearly 58% of truckload drivers were late or had to cancel a pickup or delivery due to detention at the previous customer’s facility at least once in 2023.

ATRI also found 52% of drivers ran out of available HOS on-duty time at a customer facility because of detention.

The ripple effects caused by such delays make trip planning a nightmare, adding immeasurably to the cost of moving goods. It also negatively affects driver satisfaction. Mehra said fleets are more than aware of the problem and have been coming to Trimble looking for detention time data to buttress their case with recalcitrant customers.

"They want to have those discussions with their customers, but fleets are not operating from a position of strength in this economy," he observes.

See also: Gatik touts driverless success along the middle mile in Arkansas

Fleet solutions

Grand Island Express, a temperature-controlled truckload carrier based in Grand Island, Nebraska, has an internal feedback system where drivers inform operations of in-and-out times. That data is tracked and used to predict future dwell times for those customers. This aids trip planners in producing realistic rather than best-hope schedules.

Deen Albert, VP of operations at Grand Island Express, told FleetOwner the company recently began using an AI-based dispatching application called Optimal Dynamics.

"Optimal Dynamics does the math for us on drivers' hours of service, so it appropriately assigns loads to drivers," he explained.

Overall, it maximizes their hours of service and gets them more miles, helps decrease empty miles, and gets them home on time. "It has only been in place a few weeks, and we've already seen increases in productivity. The average revenue per driver has gone up, and our average miles per driver is up, too," Albert added.

Even so, the company is still subject to the vagary of congestion and slow-moving forklift drivers. Since their main lane is the Midwest to the Baltimore-to-Boston corridor, they built a yard in Chicago. That allows road drivers more drop-and-hook opportunities without going into Chicago itself.

GIE also runs a small yard in Omaha that helps with faster turns out of Nebraska.

"I anticipate we'll continue to push on a drop-yard/relay network to continue helping the road drivers stay on the road," Albert said.

Boyle Transportation takes a slightly different approach. Laura Duryea, director of driver recruitment and professional growth, said her drivers have a high degree of latitude when it comes to routing and trip planning, and she relies on them for greater input in plotting their trips around traffic and known pinch-points when possible.

"Sometimes that's not possible, you know, or if it's super far out of route and it doesn't make any sense, then we don't want them to do that," she said. "But we want to give them the ability to make those decisions. We trust them to be the professional drivers they are and make that call."

Duryea noted that off-route miles to avoid bottlenecks are not necessarily frowned upon, and drivers might be better able to manage their rest breaks when and where they feel appropriate rather than being told when to stop.

Equipment maintenance

Uptime is a critical ingredient in optimizing the middle mile. Broken-down trucks don't make on-time deliveries.

GIE's Albert said the fleet is on a 30-month trade cycle. That might not guarantee uptime, but there's a lower likelihood of unexpected problems. That said, the trucks are on a stringent PM schedule, and they get a thorough going-over whenever a truck returns to the terminal.

"We stay on top of that pretty heavily," he noted. "We also pride ourselves on equipment that's 30 months old or less--as long as we're in a normal trade cycle."

Boyle, too, takes its maintenance and PM schedules seriously. Duryea said its PM schedule is rigid, which helps the fleet stay ahead of the pesky problems that can sideline a truck. And it is good at inspections when a truck returns to a terminal.

"People leave companies for equipment and pay, right?" she asked rather rhetorically. "If you mess with their money or mess with their equipment, or their equipment keeps breaking down and they can't make the money, guess what happens?

"It's in everybody's interest to stay on top of the equipment. That's how you bring efficiency and productivity to a line-haul segment."

The freight recession

While everything we've noted above is worth considering, fleets remain focused on fuel efficiency and keeping operating costs as low as possible.

The middle mile is pure cost, at a dollar-and-a-half or more per mile in most cases. The pressure to perform at peak efficiency and productivity has never been more intense.

To that end, Trimble's Mehra said more fleets are taking a greater interest in analyzing operational data, looking for untapped efficiencies and hidden costs. Are fleets finally realizing the value in their data?

"If you had asked me this question two or three years back, I would have said no," he said. "But something has changed in the last 12 to 18 months. Whether or not you want to call it an effect of the freight economy recession that we're going through, fleets are realizing they can get better utilization of their resources, their trucks and trailers as well as their drivers, by asking the question, 'are we doing everything right?'"

About the Author

Jim Park

Jim Park is an award-winning journalist who has covered the trucking industry since 1998. Before that, he racked up 2 million miles as an over-the-road truck driver and owner-operator pulling tank trailers. He continues to maintain his CLD. Park's previous driving experience brings a real-world perspective to his work.