Now about that truck driver shortage: is there one? Yes? Then how did it happen, and how do you stop it, or at least mitigate it? Mapping out what's brought things to this point and what carriers need to do now if they want to keep their seats filled is Tim Hindes, founder and CEO of Stay Metrics.

Hindes has been in that seat himself, having started out as a fleet driver and owner-operator, then working through a succession of positions in dispatch, marketing, and as a company executive.

"I've had the opportunity to be around the block a bit," he quips, and to feel what drivers feel firsthand. Stay Metrics conducts driver surveys and individualized analytics to help carriers assess their driver workforce and reduce turnover.

From his own experience and Stay Metrics' business and research, start here: "Drivers chronically feel underrecognized and under-rewarded," Hindes says.

Note that a driver shortage isn't the same as driver turnover, which reached 98% among large carriers during the second quarter, according to the latest analysis by the American Trucking Assns. Turnover can climb higher as a shortage gets worse, since fleets may be doing more to entice drivers from other companies to "switch sides."

But as for a shortage, carriers have been having trouble hiring enough drivers now for years; availability of drivers has even become a constraint on trucking capacity. "It's absolutely real," Hindes contends.

So what happened?

The pipeline dried up noticeably.

One root cause of the driver shortage is that the supply of people historically filling the driver role dwindled. Though not exclusively, those who might begin a career as a driver would choose that over college and subsequent "white collar" desk jobs.

In 1980, Hindes explains, about 56% of high school graduates went on to attend college, leaving 44% who didn't. For the traditionally male-dominated position of truck driver, take half that amount—carriers would compete to woo roughly 22 out of every 100 high school grads.

Trade positions would be targeting that demographic as well, he notes, and trade positions were well-stocked for labor in the '80s.

Now, 70% of high school graduates go on to college, shrinking the pool of higher potential/ likely hires to 30% and about 15 males. "So we're already down—it's a different environment we're in," Hindes says. "And by the way, in most parts of the U.S., the trades are extremely short [on labor] themselves."

Family sizes have also been diminishing. Taken together, these factors have produced a drastic effect Stay Metrics has tracked. "From 1994 to 2013—20 years—drivers under the age of 35 went from the largest group [of drivers] to the smallest," Hindes explains. "We've got retirements and deaths coming, whether we like it or not. It's real."

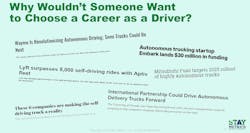

Self-driving trucks and cars are dulling the appeal to become a driver.

Gee, whatever could be helping discourage high school grads and young workers from getting into a career as a truck driver? Might all the talk and hype in the last few years especially about autonomous vehicles be having any influence?

It certainly is, assesses Hindes—but the problem for carriers is that self-driving trucks won't arrive quickly enough to fill the gap as real human drivers continue to trickle off.

"Automation will not come in fast enough. We all know it," he says. "It's not going to be an overnight thing. There are tons of regulatory and insurance issues, and it's not going to come fast enough." Meanwhile, it's become a harder sell for carriers to sway young career-minded individuals.

"If I'm talking to a prospect and I'm saying how being truck driver is a great career, don't worry about this whole autonomous thing, that's still 20 years out, they can honestly look me in the eye and say, 'Mr. Hindes, so what you're telling me is I'm going to be 42 years old and I'm going to have to start a new career,'" Hindes notes. "How do we answer that?"

The proper selection and onboarding process went out the door.

As the pool of potential truck driver hires and future appeal of the job have been decreasing, carriers have had to rush through things when it comes to new drivers, and it comes at a price.

Hindes recalls working at a carrier as a dispatcher when standards and expectations had to be adjusted. Once commercial driver's licenses were required for truck drivers, making it harder to find qualified individuals, the carrier went from seeking drivers with five years' experience to two, throwing out other sought-after things such as whether a driver fit into the company culture and so on.

"As an industry, we said, 'Okay, HR, we're going to lock you in the closet. You can now talk to anybody but a driver, and we're going to do what everyone else did: hire a recruiter,'" Hindes says. "And what's a recruiter? A salesperson."

That recruiter trying to bring on drivers for many—or most—carriers may be paid by headcount, so another problem is the recruiter could be "selling" the driver position rather than giving potential hires realistic expectations.

Driver onboarding and orientation may also be lacking (or nonexistent). "What did we do with drivers? We can't do socialization; we can't take people to lunch. We can't do an orientation," Hindes contends. "It's, 'These guys aren't making money and I'm not making money until they're out on the road, so let's get them out!'

"We push them out the door so they can start making revenue, and the only one left is the dispatcher. That's the only relationship left that that driver really has; that's his only chance of being socialized in," he continues. "I get it—you have more work than drivers to do it. That's what we're living, but there's also a price to pay for that."

As a result of all these factors, the bottom line and current reality for fleets and trucking companies boils down to this:

Carriers need to retain every driver they can, particularly in the next few decades.

So what can be done to help with this problem that's been taking shape for years and on a number of fronts? Stay Metrics has these recommendations to start, some of which are "very low-hanging fruit," Hindes says.

1. Focus on expectations.

That means both your company's expectations and those of drivers, and fixing your onboarding and socialization processes.

"Align your recruiter's message with orientation's message," Hindes recommends. Things like route, how much drivers are paid, exactly when they'll see payment after a load—these are areas where carriers need to have a "meeting of the minds" to make sure recruiters have a consistent, accurate message they're communicating to drivers.

Might be time for a reality check: "Nine times out of 10, you can't change your operation. You just need to change your message" to be sure it's realistic and truthful based on your operation, says Hindes.

And this isn't just a "prepare drivers for the negative" situation. He noted that carriers that can actually exceed drivers' expectations as they get to know the company could see drastic reductions in turnover. The better you do recruitment, selection, onboarding, and orientation/ socialization, the more your driver outcomes will improve.

2. Identify dissatisfaction.

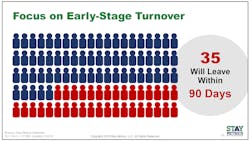

Surveying drivers can play an essential role in retention, according to Stay Metrics. The company uses a model where new drivers are surveyed at seven and 45 days and then annually.

"You really want to focus on improving expectations and early experiences," Hindes says, since Stay Metrics has found that 35 out of 100 new drivers will quit after 90 days. It's a critical period for reducing turnover.

Doing annual surveys of drivers can help identify higher-level employee trends—driver turnover may be getting worse, while service technician turnover has improved, for example. Along those lines, Stay Metrics helps carriers compare their rates with the larger trucking community to benchmark where they need improvement.

3. Intervene where you can.

Based on surveys you can do with drivers, Hindes notes, carriers can identify drivers—by what they say and do not say—who are having problems, and where the company might be able to step in and help address those before that driver's out the door.

"Do work the interventions quickly. You have to ask yourself as a company, 'Are we ready? Are we serious about retention?'" Hindes asks. To that end, he says retention needs resources behind it.

Also on interventions, Hindes recommends that fleets identify a "peacemaker" who's not a dispatcher or recruiter to do these—"somebody that that driver's really going to get along with and feel comfortable with, who will put that driver at ease, who will build trust and credibility, and their follow-up will be good."

"A lot of carriers take some time to figure out how they're going to deal with these [interventions], but the better you do them, the better your retention is going to be," he says.

4. Do exit interviews.

Fleets can learn a lot from drivers who've chosen to leave, but not on their own, according to Stay Metrics.

"Providing a voice to that driver, I will tell you, it's an excellent thing," Hindes contends. "You've got to do exit interviews, but don't try to do them yourself and don't try to move them to some other part of the company." Stay Metrics suggests that a neutral party is necessary here.

"Drivers will tell a trained third-party interviewer things they will absolutely not tell the company," Hindes says. "There's an art form to doing that interview, getting that driver to understand it's confidential and the company only sees data in some aggregate form, and then letting him speak."

5. Recognize and reward drivers.

While research supporting driver rewards programs may be lacking, Stay Metrics believes these can be a differentiator in this employment demographic that feels "chronically underrecognized and under-rewarded."

"Why does every retailer, every hotel have a rewards and loyalty program? Because they work," says Hindes.

But it has to be done right, he adds: "Yes, drivers get into these, but you have to have what I call an 'abundance mentality.' Too many companies get into trinkets and trash—'If you do all these things for X amount of time, you're going to get a company jacket.'"

He gives the example of one carrier Stay Metrics worked with that went from $1,000 in potential points a driver could earn in a year to $2,000. "It's absolutely sticky. What it does when you have that abundance mentality is that people are getting stuff all the time," he says. "They're getting a flatscreen TV, and three months later they've got a bunch of video rentals.

"What you want to have happen is if they're thinking of leaving you, that [the rewards program] is substantial enough that they're like, 'Man, that's kind of nice—I don't want to walk away from that,'" Hindes continues. "But it's not a substitute for good pay packages, and it's not a substitute for onboarding and orientation."

About the Author

Aaron Marsh

Aaron Marsh is a former senior editor of FleetOwner, who wrote for the publication from 2015 to 2019.