A year ago, texting and dialing while driving was the most frequent risky behavior of Central Oregon Truck Company (COTC) drivers. This summer, it fell to No. 7 on the fleet’s list of at-risk behaviors. While technology has played a significant role in reducing distracted driving within the fleet, creating a safety culture has made a big difference.

“I’ve let guys go for stuff that was just egregious as far as distractions go,” said Brad Aimone, director of driver safety services for Central Oregon Truck, which uses in-cab videos of distracted driving incidents as teaching tools for drivers. “We show them the footage and say, ‘Hey, your family relies on you to make a living to keep a roof over your head. Is it really worth it? Is this worth your livelihood?’”

The flatbed carrier, which operates more than 300 trucks and has nearly 300 drivers, has had a three-strikes policy on distracted driving for the past two years. A driver caught using a handheld phone while driving gets a warning and mandatory retraining. The second event within 12 months leads to a 48-hour suspension without pay. A driver with three distracted driving events in the same year is fired.

Despite the strict policy — or perhaps because of it — more than half of COTC drivers have been with the fleet for more than a year, Aimone said. The carrier continues to get rave reviews from drivers, and for the past seven years, it has been listed on the CarriersEdge annual Top 20 Best Fleets To Drive For.

There is no multitasking

“A lot of people will tell you that they don’t get distracted, that they can think about more than one thing at once, and that they can multitask. That is actually not true,” CarriersEdge CEO Jane Jazrawy told FleetOwner. “You can’t multitask. What you can do and what your brain does is just switch between things very, very rapidly. You’re not doing it simultaneously. You’re switching.”

When a driver’s brain is switching between tasks, attention is diverted. “When you are driving, doing anything else that’s not driving can be a distraction,” she explained. “If you are using a phone, for example, that is the biggest distraction you can have. And the more distraction you have, the more likely you’re going to be in a collision.”

CarriersEdge offers fleets online courses that show drivers how easily the mind is distracted when focusing on more than one task at a time. The course starts simply by showing the names of colors written in that color — “red” is in red type, “blue” is blue, etc. Drivers are asked to identify the color of the word, which Jazrawy notes is easy since the color matches the word.

But the colors are switched in the second part of the exercise; for example, “red” might be written in blue and “yellow” written in green. “When you try to read the word, you’re distracted by the color of the word — or when you’re trying to say what the color is, you’re distracted by what the word is,” Jazrawy explained. “You’ve got two things coming at you at the same time. You can do it, but you’re a lot slower.”

This, she said, illustrates how a driver’s reflexes are slower when trying to use a phone and drive simultaneously. “It’s like patting your head and rubbing your stomach at the same time. If you concentrate on where your brain is, you’ll realize that you start thinking about one more than the other at any given moment. That’s the basis for distraction,” Jazrawy said.

A steady problem

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), distraction on the roadways has been a constant problem in the U.S. over most of the past decade, which attributed about 23,000 highway deaths to distraction between 2012 and 2018.

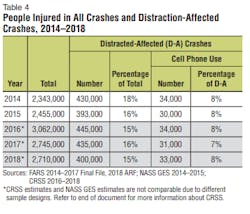

In 2018, there were 2,841 people killed — and more than 400,000 injured— in motor vehicle crashes involving distracted drivers, according to the most recent numbers from NHTSA. Of all fatal crashes in 2018, 8% were attributed to distracted driving, according to a study released earlier this year by NHTSA. That study also noted that 8% of fatal crashes, 15% of injury crashes, and 14% of all police-reported motor vehicle traffic crashes in 2018 were reported as distraction-affected crashes.

Between 2014 and 2018, traffic crashes involving distracted driving have wavered between 13% and 16%, NHTSA reports. And those numbers might be underreported as not all police jurisdictions include distraction as a distinct reporting field. Also, much of the crash data relies on the at-fault driver to self-report distraction as a cause, which NHTSA infers as another reason driver distraction is underreported.

Distracted driving is the new drunk driving, COTC’s Aimone said. Research from the U.K.-based Transportation Research Lab showed that drivers using a handheld phone while driving can have increased delayed response times and stopping distances more than alcohol.

Passenger problem

With more in-cab video and other technologies being used to monitor the behavior of professional drivers, the greater risk on the roads might be from four-wheeled vehicles. “Our commercial drivers are some of the best-trained and most well-intentioned people out there,” explained Chris Orban, vice president of data science for Trimble Transportation. “It’s a tough job. It requires constant attention and comes with a lot of responsibility.”

Orban is less convinced of the general motoring public’s skills and focus on the roads. COVID-19 has exacerbated this stark contrast between professional drivers and passenger car drivers, he said. At the start of the pandemic, when more Americans stayed home and didn’t drive as much, it changed their behaviors— either because they weren’t driving much or because those who were driving were dealing with less traffic.

“Members of the public who take a couple of weeks off from driving don’t forget how to drive, but behavior changes as complacency sets in,” Orban explained. “And as traffic lessens, I see people taking more risks.”

As truck drivers worked to keep supply chains connected and keep up with increased demands for deliveries, Orban said other motorists were making the roads riskier. And while more people have resumed driving more since the early days of the pandemic, he noted that people might be more stressed, frustrated and fatigued, causing their own distractions.

Orban said truck technologies, such as advanced driver assistance systems, can increase the defensive driving abilities of professional drivers. Dashcam and other video technologies can also help exonerate commercial drivers involved in crashes with distracted motorists, he noted.

Safety culture

A study by the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute’s (VTTI) National Surface Transportation Safety Center for Excellence backed up what Orban has seen. The 2019 report found that six of nine fleets improved safety outcomes after adopting at least one advanced safety technology coupled with a strong safety culture.

Each of the carriers in the VTTI study, which had all been flagged as high risk by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, reported no single fix to make their fleets safer. The carriers found a comprehensive approach was the best way to improve fleet safety and reduce crashes. Each of these trucking companies targeted safety improvements for hiring safe drivers, training current and new drivers to safely operate trucks, developing proactive management programs to encourage safe driving, building strong safety cultures to support safety, improving driver scheduling to reduce fatigue, equipping trucks with technologies designed to assist the driver, and ensuring the trucks are in good working condition through vehicle maintenance.

Aimone of Central Oregon Truck, which is a Great West Casualty carrier, said safety should be the top concern of his drivers. Each Wednesday, the fleet goes over Great West’s Value-Driven Driving initiatives, which are seven essential driving techniques for commercial drivers, including avoiding distractions, maintaining proper speed and adhering to proper following distances.

“At the end of the day, the name of the game when you’re operating a Class 8 tractor-trailer is to protect life,” Aimone emphasized. “And we just tell them that. Yeah, we move freight here and we run miles. Our No. 1 job as professional truck drivers is not to get the load from A to B—and a lot of them come in with a perception that that’s what we’re expected to do. Our No. 1 job when we’re behind the wheel is to protect life. And that can include dealing with distracted drivers around us. How can you defensively set yourself up for success?”

About the Author

Josh Fisher

Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief Josh Fisher has been with FleetOwner since 2017. He covers everything from modern fleet management to operational efficiency, artificial intelligence, autonomous trucking, alternative fuels and powertrains, regulations, and emerging transportation technology. Based in Maryland, he writes the Lane Shift Ahead column about the changing North American transportation landscape.