Fleets Explained: How the U.S. Interstate System grew the nation and trucking industry

Before the First World War, rail was the quickest way to move freight—or anything else—across the vast United States. Few trucks had cargo capacities greater than two tons, and most roads between cities were unpaved and challenging to traverse.

The drive to connect America by highways

Driving is the most popular way for Americans to travel great distances. A road trip is as American as tackle football and hamburgers. And trucks—now much heavier and powerful than the World War I era’s two-cylinder motor wagons—rely on divided highways as freight lanes.

Trucks moved 72.7% of U.S. freight in 2024, accounting for 76.9% of tonnage revenue, according to American Trucking Associations. While rail dominated goods movement from the Civil War to World War II, it made up just 10.6% of U.S. freight tonnage in 2024.

When rail capacity was stretched to its limit during World War I, the nation turned to trucks. The trucks, in turn, tore up the dirt roads that connected most states. However, the early truck models showed their potential value, according to a history by the Federal Highway Administration.

The value and flexibility of moving goods by road instead of rail became obvious to truck makers, but roadbuilders were worried about the damage that heavier trucks could cause. Many roadbuilders of the time wanted trucks to be limited based on what byways of the day could handle. In contrast, according to the history book America’s Highways 1776-1976, manufacturers wanted roads strengthened to handle their bigger trucks.

Early trucking interests used the slogan, “build the roads to carry loads,” while the opposition pushed for freight loads limited to existing infrastructure. Maybe it was the rhyme, but trucking common sense won out, according to Thomas H. MacDonald, longtime chief of U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, a precursor of the Federal Highway Administration.

The war also showed that the military needed more efficient roadways. A 1919 cross-country military truck expedition along the incomplete Lincoln Highway from the White House to San Francisco Bay took two months to traverse more than 3,000 miles. The 46 trucks, five ambulances, 11 cars, nine motorcycles, and other equipment, averaged just under 6 mph and featured repeated breakdowns and struggles, such as repairing dozens of wooden bridges along the way.

Those struggles helped demonstrate the nation’s need for a transcontinental highway system that could benefit its defense system and support its population and economic growth.

Eisenhower experiences pave path for interstate road network

Among the U.S. Army personnel on the 1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy was 28-year-old Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who filed a memorandum about the trip for his superiors. His reporting on the mission would help lead to the first federally-backed interstate system of U.S. roads.

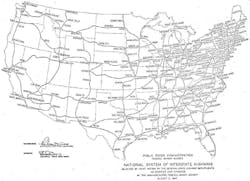

The U.S. Numbered Highway System was developed in 1926. This created formal designations for new and long-standing highways, such as the old Boston Post Road (from Maine to Miami) being designated as U.S. Route 1. Most of the Lincoln Highway, which much of that 1919 Army convoy traversed, became U.S. Route 30. While federally organized, state transportation departments are responsible for building and maintaining these roads.

The network of connected state roads improved the U.S. motor-powered transportation system over the following decades. However, as car and truck popularity grew, travel on these surface roads grew less efficient and safe. While plans were discussed and legislation passed over the ensuing years, it wasn’t until the allies won World War II that today’s U.S. Interstate System began to take shape.

During World War II, General Eisenhower saw the efficiencies of Germany’s Reichsautobahn highway system for defense purposes. After being elected president, Eisenhower championed an interstate highway system during the mid-1950s.

Studies of the day found that the U.S. had some 48 million passenger cars, 10 million trucks, and 250,000 buses operating on its more than 3.3 million miles of surface roads. In a 1955 report to Congress, Eisenhower noted how the nation’s economy and future could benefit from a better way to move people and goods across it. So, they set out to create a freeway network connecting every U.S. city with at least 50,000 residents.

“Our unity as a nation is sustained by free communication of thought and by easy transportation of people and goods,” Eisenhower said. “The ceaseless flow of information through the Republic is matched by individual and commercial movement over a vast system of interconnected highways crisscrossing the country and joining it at our national borders with friendly neighbors to the north and south.”

Despite railroad interests' opposition to the initiatives and complicated legislative battles to determine infrastructure funding, the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 paved the way for financing, designing, and engineering the interstate system we use today.

How much did it cost to build the Interstate system?

While Eisenhower wanted the highways funded by toll roads, his committee in charge of the system found it unfeasible outside major metro areas. Other funding ideas couldn’t get through Congress until legislators and the White House settled on creating the Highway Trust Fund (that has its modern problems), which uses fuel taxes to pay for interstate highway funding. The 1956 law called for the federal government to fund 90% of highway construction with states paying the rest, along with maintenance.

The first federal fuel tax, introduced in 1932, was 1 cent per gallon. It was raised to 3 cents per gallon to fund the Interstate project. That same tax continues to feed the Highway Trust Fund. Congress last raised it to 18.4 cents per gallon in 1993. And it hasn’t been changed since. In 1956, gasoline averaged 30 cents per gallon (including the tax), making the federal tax a little more than 11% on fuel. In March 2025, gasoline averaged $3.069 per gallon (including the tax), which means the federal gas tax is about 6%.

As vehicles become more fuel efficient, they use less diesel or gasoline, reducing federal fuel revenue. Electric vehicles don’t use fuel pumps, so they aren’t taxed, which has led some states to consider charging vehicles based on miles traveled.

Officially named for the man who convinced America it would benefit from it, the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, was completed in 1992 when I-70 through Colorado’s Glenwood Canyon opened.

It was a mere 23 years over schedule and $89 billion over budget (in 1956 dollars). Originally expected to take 12 years and $25 billion; it took 35 years and $425 billion in 2006 dollars, according to USA Today. That would be about $676 billion in 2025.

But Ike knew the price would be worth it. “Its impact on the American economy—the jobs it would produce in manufacturing and construction, the rural areas it would open up—was beyond calculation,” he wrote in a memoir about his first term in the White House.

The FHWA backed that claim by finding that the Interstate System increased the nation’s productivity by 25% and grew the U.S. economy between 1950 and 1989. From 1957 to 1996, the Interstate fueled a $3.5 to $4.1 trillion boost to the American economy in 2020 value, according to the Reason Foundation.

Though the Interstate Highway System was declared completed during the first Bush administration, it isn’t actually finished. Not only are expansions and changes still happening, but part of the original vision is still missing.

Interstate 70, which runs east from Utah to just outside Baltimore, is interrupted in Breezewood, Pennsylvania. Drivers must take U.S. Route 30 on surface roads with traffic lights before re-entering the interstate.

How highway standards are maintained

The highway systems were all required to be at least four lanes wide (two in each direction) and have no at-grade crossings. They also had to be freeways, but Congress and the Department of Transportation have allowed local tolls by various state requests.

The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) defines Interstate highway standards, with some federal exceptions.

These standards include no traffic lights or cross traffic, toll booth restrictions, exit and entrance ramps specifications, and more. AASHTO also developed the Interstate numbering system, which mirrors the U.S. Numbered Highway System.

While there are exceptions, the general rules for Interstate highway numbers are:

- Single and double digits: Primary Interstate routes use numbers between 4 and 99, such as I-5 and I-90

- Even numbers: Primary Interstate routes with even numbers run east-west, such as I-10

- Odd numbers: Primary Interstate routes with odd numbers run north-south, such as I-95

- Number sizes: The farther south and west a route, the lower its number; the farther north and east, the higher its number: I-5 runs along the West Coast and I-95 runs along the East Coast; I-10 runs across the South while I-90 runs across the North

- Triple digits: Spurs, loops, and byways off the primary Intestates have three-digit numbers that end with the primary Interstate’s digits, such as I-190, a spur off I-90 (Massachusetts Turnpike); or I-495, the Capital Beltway around Washington, D.C., that connects with I-95

- Non-interstate Interstates: Some highways considered Interstates don’t cross state lines, such as I-4, which runs between Tampa and Daytona Beach, Florida. Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, which do not border the lower 48 states, still have Interstate systems. However, these highways use A, H, or PR prefixes, such as H-2 in Hawaii, instead of the I-prefix used throughout the rest of the nation.

How trucking uses the Interstate Highway System

As the Interstate system grew, so did the trucking industry as it could offer much cheaper shipping costs than rail. As intermodal containers were developed, it benefited overseas importers and exporters, who could easily transport goods on trucks between trains and ports.

Longhaul and regional trucking operations are generally designed around the Interstate system. Because all highways require partitions between traffic and multiple lanes, it is safer for trucks to travel at faster speeds. As interstate trucking grew in the 20th century, so did the travel stop business. Drivers nationwide could benefit from fueling, food, and other amenities off the highways.

A 2024 study by Trucker Path, a navigation and fleet management solution provider that helps drivers find parking and other amenities on the road, found better truck parking along the northern and western Interstates.

Based on parking availability, truck stop ratings, and fuel prices, the ratings highlighted Interstate 90, I-5, and I-44 as the most friendly to drivers, according to the Trucker Path findings. I-90 runs from Seattle to Boston, I-5 extends up and down the West Coast from the Mexican border to Canada, and I-44 runs from northern Texas to St. Louis.

Truck parking is integral to driver operations. Drivers must take various breaks and multi-hour rests, and finding safe parking can create problems. A previous Fleets Explained article detailed how truck parking works.

How multi-highway lanes (are supposed) work

Multi-lane highways are designed to make traffic more efficient, so that slower vehicles don’t impede faster vehicles. Here is how a three-lane highway (in one direction) is supposed to work for various vehicles.

- Right lane: For entering and exiting divided highways, and for slower moving vehicles

- Center lane: For traveling at typical highway speeds

- Left lane: For passing and overtaking slower vehicles; in most states trucks are prohibited from using the left-most lane except for passing or driving through some construction areas

While that is how highways should work, many who travel these roads don’t seem to use them that way. On two-lane highways, all drivers should travel in the right lane and move to the left lane to pass slower vehicles.

Large volume traffic states, such as California, have highways with as many as five lanes traveling in the same direction. The California Department of Motor Vehicles created this video to show how highway traffic is supposed to work: