The case for speed limiters: More political than technical?

Is the Dept. of Transportation “cherry picking” research to support the rulemaking to require speed limiters in heavy-duty commercial vehicles? At least one source—a study that is cited often as providing evidence to support the rule—raises a number of concerns the DOT glosses over, or ignores altogether, including speed differentials, driver fatigue, fuel efficiency, and the overall cost-benefit analysis.

The first footnote in the “executive summary” of the DOT proposal refers to a 2005 paper, “Cost-Benefit Evaluation of Large Truck-Automobile Speed Limits Differentials on Rural Interstate Highways,” by researchers at the Mack-Blackwell Rural Transportation Center (MBRTC), a College of Engineering program at the University of Arkansas.

In that initial cite, and in three other footnotes, the paper “confirmed the common-sense conclusion that the severity of a crash increases with increased travel speed”—as, indeed, basic physics determines.

However, while the DOT rulemaking mentions the issue of speed differentials, the 118-page document does not reference the MBRTC report with regard to its primary subject matter. Indeed, after opening the “Safety Benefits” section by citing MBRTC, the proposal refers to two other studies that “observed no consistent safety effects of differential speed limits compared to uniform speed limits.”

The MBRTC report, a survey of available research at the time, also cites those “inconclusive studies,” and says the research did not address the impact of voluntary speed limiters, prevalent even 10 years ago, and so those studies were “inherently flawed.”

More broadly, “the large number of safety studies that were discussed in the literature review indicates that this issue has received a great amount of attention,” the researchers write. “Unfortunately, many of the studies involve more advocacy than science.”

The MBRTC study notes that proponents of lower truck speed limits argue that trucks require longer braking distances for any given speed and lower truck speeds help equalize the stopping distance. Truck drivers surveyed by the researchers, however, contend that their higher seat position allows a longer sight distance (multiple vehicles forward), reducing the effect of the differences in braking distance (to say nothing of the greater stopping power of modern disc-brakes and other safety technologies). The truck drivers are more concerned with the negative effect of greater speed variation and the number of interactions among vehicles.

“It is likely that both of these arguments are correct,” the paper says. “This would indicate that differential speed limits have two effects:

- the positive effect that results from improved vehicle dynamics (braking and maneuvering) for trucks at lower speeds; and

- the negative effect of increasing speed variation and the number of interactions among vehicles.

"These two effects of differential speed limits act in opposite directions and ultimately result in no observable effect on highway safety data.”

Driver viewpoints

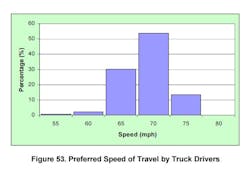

Based on a questionnaire, the MBRTC report summarizes driver sentiment on the matter of speed differentials.

Two scenarios that dominated the drivers’ concerns were associated with on-ramps, according to the research.

- The first safety issue related to trucks being “trapped” in the right lane and the increased risk of continually encountering merging traffic.

- The second issue involved trucks not being able to reach traffic speed when merging into traffic flow. They also indicated a concern that lower truck speeds result in congestion and clustering of traffic and bottleneck situations on highways.

Additionally, 87% of the truck drivers responded that speed differentials, whether due to regulated speed limits or company policies, increase the risk of accidents. Truck drivers also raised the issue of unsafe maneuvers by passenger vehicle drivers in overtaking and passing much slower trucks.

If left up to them, the truck drivers indicated that a uniform speed limit of 70 mph for both automobiles and trucks would be both the safest and the most efficient configuration for rural interstate highways. The researchers note that drivers who generally have the ability to travel faster than 70 mph (owner-operators) also agreed that a 70 mph limit would be most appropriate.

Safety managers, however, were somewhat more cautious. While they agreed that differential speed limits increase the probability of accidents, many felt that a uniform limit of 65 mph would be the best alternative.

“Some managers indicated that new, less experienced drivers might benefit more from lower truck speeds, with more experienced drivers being able to handle the higher speeds,” the study says. “Other managers indicated that this policy would put less experienced drivers at additional risk due to the increase in the number of vehicle interactions that they would experience.”

Driver fatigue

Noting the significance of driver fatigue in crashes, the MBRTC study suggests that while there is no empirical data indicating that increased speed increases fatigue, there are studies that have found that operating time has significant impact on truck driver fatigue.

“One of the methods of reducing driving time and fatigue without reducing transport efficiency or driver pay, would be to travel at a higher speed,” the paper says. “From an hours-of-service perspective, an important issue is whether it would be safer to drive for 10 hours at 70 mph than it would be to drive for 11 hours at 64 mph.”

However, most of the company safety managers indicated that traveling at higher speeds results in more fatigue. Even when drivers are allowed to use higher speeds, they do not get to their destinations sooner because they stop more frequently and take longer breaks, the managers responded.

In response, most of the truck drivers stated that their driving time between stops is independent of speed and that their stops are based on time rather than distance. But the drivers did indicate that, if the pick up and delivery windows are not adjusted for the higher speed, there is no benefit in getting to the destination early.

Cost savings

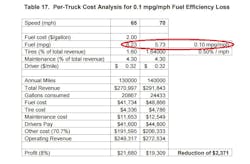

One of the primary reasons for carriers to limit the speed of their trucks is the reduction in fuel consumption, and in ideal situations this is certainly true, the MBRTC report explains. But, in addition to the absolute vehicle speed, speed variance in the traffic flow also has an effect on fuel efficiency when both trucks and automobiles decelerate and accelerate to maneuver around slower traffic.

“The negative impact of traffic speed variation on fuel efficiency has not been addressed in the research literature or as a policy issue,” the study says. “When speed policies are considered, it is important to consider that the driver effect is estimated to be double the effect of vehicle speed. It might be possible that by improving retention, the costs associated with higher speeds might, to some extent, be offset by the ability of more experienced drivers to conserve fuel.”

The study also notes that owner-operators, “who have direct knowledge of their individual operating costs,” as a group preferred higher speeds due to the increased revenue, more flexible scheduling, and the benefits of increased personal time.

Indeed, the researchers point out that their financial cost-benefit analysis illustrates how the results are very sensitive to estimates of the operational costs associated with increased truck speed.

“Unfortunately, although there are many opinions, there is very little verifiable data that can be used to make these estimates,” the paper states.

The study’s results ranged from an annual decrease in net profit per truck of $2,371 for the higher estimates of speed-related operational costs, to a net profit increase of $442 for the lower estimates.

“Even the costs derived using the higher estimates could be offset, to some extent, if the higher speeds and increased pay would improve driver retention,” the study says. “In addition, the number of trucks necessary for the same annual mileage would be reduced, lowering the truck inventory costs for commercial fleets.”

Popular misconceptions

One of the common misconceptions that motorists have is that they are often passed by trucks, the MBRTC report notes. However, results of the researches’ simulation study indicated that the frequency of automobiles being passed by trucks is very low.

Using the traffic speed data from the uniform 70 mph sites in the study, an automobile traveling at the mean traffic speed (71.5 mph) would be passed by only 30 trucks during a 1,000 mile trip on a rural interstate.

Similarly, many sources in the popular press refer to the statistics that indicate that more than one-third of the highway accidents are associated with “speeding.”

However, speeding is defined as “traveling faster than the posted limits” or “traveling too fast for conditions.” Because there is no differentiation of these two categories in much of the literature, the effect of the posted speed limits on the number of accidents and fatalities is probably highly exaggerated in the popular literature, the report states.

Conclusion

“Although there is an abundance of opinion on many of the issues, there is very little empirical, verifiable, and scientifically valid data available from either public or private sources,” the MBRTC study concludes. “It is evident that there is a need for additional research in many of the areas relevant to the maximum speed for heavy trucks. The decisions pertaining to the state regulated absolute and/or differential speed limits for trucks will continue to be a political, as well as a technical issue.”

Does the DOT proposal address all of these issues? I'm not convinced. But, to be fair, I've yet to dig as deeply into the all-important crash data on which the lives-saved projections are based—and I was already familiar with the MBRTC study.

Gathering evidence, publishing the government's thinking, and opening the process up for review is how the rulemaking process is designed—and a first draft is what NPRMs are for. Still, the proposed rule was held for White House review for more than year, though we don't know why. On the other hand, big trucking and "safety advocates" support speed limiters, and Congress is backing the regulation, too; and that's an irresistible coalition.

So something's coming—we just don't know how fast.

About the Author

Kevin Jones

Editor

Kevin has served as editor-in-chief of Trailer/Body Builders magazine since 2017—just the third editor in the magazine’s 60 years. He is also editorial director for Endeavor Business Media’s Commercial Vehicle group, which includes FleetOwner, Bulk Transporter, Refrigerated Transporter, American Trucker, and Fleet Maintenance magazines and websites.

Working from Beaufort, S.C., Kevin has covered trucking and manufacturing for nearly 20 years. His writing and commentary about the trucking industry and, previously, business and government, has been recognized with numerous state, regional, and national journalism awards.