Feds not liable for truck damaged during botched drug sting

A federal court has ruled that the Drug Enforcement Agency does not have to pay a truck owner whose vehicle they commandeered in a botched drug sting operation – without his knowledge or permission – in which the agency's confidential informant driver was shot dead and the truck was damaged.

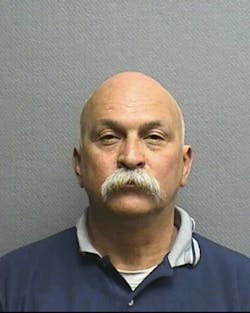

Says truck owner Craig Patty: "I took the federal government to court and lost. They refused to pay for my truck that was shot up and damaged because of their operation which I knew nothing about." He says that the insurance company wouldn't pay for damages either because it involved a criminal action. "It's in the fine print," he says.

"Everybody is shocked at this kind of ruling [from the federal court] and just appalled that the government has the ability to use a private citizen’s personal property without their consent and that it can withstand judicial scrutiny," says Patty's co-counsel, attorney Fred Shepherd.

The complex story, pieced together from trial documents and interviews, offers a view of a federal agency that apparently did not have a handle on its own operations, disregarded Constitutional law – according to the truck owner's lawyers – and then asked the courts to seal documents because it might reveal confidential information about their failed operation.

The Set Up

Steven Craig Patty formed his small trucking company "Craig Thomas Expeditors" in July, 2011. He purchased two Kenworth T600 trucks and contracted two drivers. One of them was Lawrence Chapa. Patty didn't know that Chapa had a criminal record including resisting arrest, possession of cocaine and assault. According to Houston police, the 53-year old Chapa had a hot temper; he had been arrested for grabbing a tire from a Goodyear store's lobby display and throwing it at a mechanic because he believed they were overcharging him. He also had a history of drug use. According to journalist Leif Reigstad, who wrote about the sting operation and resulting trials for the Houston Post, Chapa's nickname was "Senor Smoke."

None of this showed up in searches when Patty performed his due diligence before hiring Chapa as a contract driver. And it wouldn't. His CDL record would be clean if Chapa was a confidential informant for the DEA. "He had driven for me for five weeks," says the Houston-based Patty. "I had no idea about his background."

The DEA will not confirm whether or not Chapa was one of their confidential informants, but court documents verify that this was the case.

Chapa was driving back from California and called Patty from New Mexico. He was having problems with his truck. He said that a buddy of his in Houston had the needed part and he would drive there and get the repairs taken care of during the upcoming Thanksgiving holiday. Patty okayed the idea. "Chapa told me: 'If you’ll just let me take this truck to Houston, I can have it repaired during the holiday and we won’t accrue any downtime. I’ll bring it back Friday after the holiday.' And I said, 'Well, okay, that sounds like a good plan.' And so I agreed to that. Well that’s not what he did."

Instead, days later Patty received a phone call from a colleague who told him that his driver was shot dead while carrying a load of marijuana. Patty was shocked. As far as he knew, the truck was being repaired in a Houston shop.

Then the calls from law enforcement came. Investigators asked if he knew anything about his truck hauling illegal drugs. Then the lies followed, Patty said. "They said, 'the truck was taken into Mexico, and it was loaded there. Then they crossed back over the Rio Grande.' And I just let them keep talking for a while. I said: ' Look, buddy, I got a tracker in that truck. I know the longitude, latitude, I know what gear it was in and when it started and stopped. I know everything about it. And I said, 'That truck never went to Mexico.' It got real quiet on the phone; it pissed him off. Then they started interrogating me like I was a part it when they knew full well it was their own operation."

A Simple Plan

Court records state that on November 21, 2011, DEA Task Force Officer Fernando Villasana, a Houston Police officer who was federally deputized called DEA agent Keith Jones to tell him that he was organizing a sting involving a confidential informant driver (Chapa) who was asked by someone in the Zeta drug cartel in Mexico to transport 1,800 pounds of marijuana from Rio Grande City, Texas to Houston. Villasana said that the driver had made up a story about having to get repairs done on the truck and that the owner knew nothing about the drug cargo.

The DEA devised a plan to keep the truck under surveillance by undercover vehicles and aircraft until the narcotics delivery took place. At that point, law enforcement would converge and arrest the buyers who they suspected were associated with the Zeta drug cartel. [It is still not confirmed if they were associated with the cartel or not.]

Chapa stayed at a Holiday Inn near the Mexican border where he left the keys in the cab so someone could drive it elsewhere to be loaded during the night. The next day, Chapa drove the truck north to Houston loaded not with 1,800 pounds of pot but less than 300 pounds. He was told by his contact that only part of the shipment made it through the border, but that he should make the run anyway and take the truck to the designated off-loading location. Chapa told his law enforcement handlers about the change, and they decided to continue with the sting operation anyway despite the load being much less than they had expected.

They also had arranged for Chapa's truck to pass through the Falfurrias, Texas checkpoint without hindrance.

"A Quarter Mile Stretch Of Mayhem"

Chapa was having trouble finding the drop-off point because he was receiving changing directions from a man named Martin Hernandez who Chapa believed was working for a man only known as 'Mauro,' who put the deal together. Chapa may have gotten lost and was having a difficult time staying on the road talking to Hernandez while also trying to keep his handlers informed of his location. Villasana's team had trouble keeping up with Chapa, too, as his truck had to change lanes quickly at one point so he could take an exit toward Hollister Street in northwest Houston.

When Chapa's truck arrived at the designated location, he waited, knowing that he was being watched and protected by undercover officers in vehicles and hiding behind bushes and fences. He didn't know that he was also being observed by heavily- armed men arriving in three SUVs who were planning to rip him off.

According to trial records, one of the men, Fernando Tavera, jumped on the cab's step and held a gun to Chapa. He tells Chapa that he and his crew just want the cargo and that they won't hurt him if he complies. Chapa pleads for his life and, terrified, snugs into the sleeper berth to hide. While two more men reach the cab, Tavera's gun goes off accidentally. Nobody is hit as the bullet plunges into the roof of the cab.

Police hear the shot and swarm for the truck. What happens next is unclear as accounts vary. Crew member Ricardo Ramirez is now driving the truck hoping to escape but the road is a dead end and the truck is too large for a U-Turn. Tavera, trying to flee the frenzy runs and is hit by one of the DEA agent's car. He bounces off and is run over by another agent's vehicle. He is taken alive and handcuffed on the ground. Meanwhile, Ramirez jumps out and the truck is rolling slowly with no one in control. It stops when it hits a concrete wall.

Patty later learns: "Down the road a little way a school bus is coming around the corner and a Harris County Sheriff slammed into that school bus. It was [empty of children], thank God. But you have about a quarter mile stretch of mayhem. It's a Wild West shootout, and my driver is dead in the back of my truck." Chapa was shot ten times.

During the confusion, a Harris Country Sheriff's deputy was shot in the leg by a member of the DEA task force. The injury was not life threatening.

One remaining question is how did the robbers know about the drug shipment?

During the series of trials, it came to light that the robbers allegedly belonged to a group known as the "DeLuna crew" headed by Eric DeLuna. It is alleged that Hernandez told him about the cargo and DeLuna put together a group to rip off the truck.

Tavera, the man who threatened Chapa and was hit by multiple police vehicles, received a 35-year sentence for attempted armed robbery; Ricardo Ramirez, who shot at Chapa pled guilty to murder and received a 30-year sentence; Alfred Gomez, who also was charged with Chapa's murder, was found not guilty. The ringleader, Eric DeLuna, pled guilty to attempted robbery and was sentenced to 30 years. The case against Hernandez was dismissed for lack of evidence. Mauro, the alleged drug broker, is at large.

The Truck Owner's Case Against the Government

Craig Patty's claim seems simple enough. Federal agents used his truck for a government operation without his consent, it was damaged, and Patty wants to be paid for the damages both financial and emotional.

He took his case to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, Houston Division where the judge ruled last year that Patty didn't deserve a penny. Although, the judge did not dispute his claim of the facts – all of what Patty alleged about his losses were true – District Judge Lee Rosenthal said that the government was within its rights to deny Patty's claim for restitution because the agents acted within their legal authority to make judgment calls when on the job. One of their calls was to use Patty's truck without permission.

Patty's co-counsel, Fred Shepherd of the Vickery Law Firm, said of the ruling: "The judge's analysis is that the law enforcement officers under the law are afforded certain flexibility when they have to make judgment calls with regard to undercover operations or police operations. She believed that there was some discretion on the part of the undercover officer who was running the agent. Because she thought that there was discretion involved and his judgment was not to get Patty’s permission to use the truck she thought that exclusionary provision in the law resulted in the government prevailing in the case as a matter of law, not on the facts."

He adds: "This type of ruling, in our judgment, ignores the Constitution, ignores the privacy rights of individuals who are just trying to make a living, an honest living… Even if the district judge was right [applying the law], the law needs to change because this completely tramples what we believe the Constitution protects."

The attorney was also dismayed that the judge sealed many of the documents in the case. "We think that these types of cases should absolutely, positively not be litigated in secrecy, that the public has a right to know what their government is doing. The government is the one that moved to seal all the proceedings, all the hearings, all the filings for the most part."

Patty believes his damages include $133,532.10 in economic compensation to his truck and business as well as $1,483,532.10 million in personal damages. "Remember," said Shepherd, "he had two trucks at the time. He lost half of his business." Adds Patty: "I had worked in the pharmaceutical business for 16 years and had a 401-K that I was now having to pull out to make ends meet because my two-truck business was now a one-truck business."

Patty has feared for his life since the sting. "Helicopters from the local TV station flew over the scene and showed the license plate of my truck. That comes back to my address for all of the internet to see." He is concerned that members of the drug cartel that smuggled the contraband across the border might think he's part of the government operation and retaliate.

"Patty has suffered, and the medical records support this," Shepherd says. "He started having heart palpitations, anxiety attacks. He was terrified for his family and so he did have personal injury damages associated with being worried as hell that these guys were going to come after him. They killed his driver… It’s logical to think that he, his kids or wife may be next and. He'll tell you about how they lined up all their guns in their living room, because they were scared that they would have to defend themselves."

On February 1, Patty's case goes to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans. Patty's lead attorney Andy Vickery will have 15 minutes to present his case and another five minutes for rebuttal.

If Patty loses his case in the Appeal court, the only possible legal step is the Supreme Court. Would they take it to the nation's high court? "We haven’t made any decision on that and some of it would be based on what the Fifth Circuit says and what it holds," says Shepherd.

About the Author

Larry Kahaner

Larry Kahaner is an author, journalist, and former FleetOwner contributor.