Tractor and Trailer

It’s been 40 years since diesel fuel was last viewed as cheap and 50 years since the first federal Clean Air Act was passed. In the decades since, a vast whirlwind of societal, political, economic and technological change has remarkably recast trucking into a solidly green industry. Yet reducing fuel consumption by integrating the design of highway tractors and trailers to drastically slash their wind resistance remains the holy grail of aerodynamics for commercial vehicles.

The reason why has not to do with the laws of physics, but with three simple facts of life about over-the-road trucking:

- If the vast majority of van/reefer trailers did not need to be uncoupled from tractors over and over, then their manufacturers could easily design them to be aerodynamically “married.”

- If they existed, such marriages would be doomed to frequent divorce—as tractors cycle out of fleet service far more quickly than trailers.

- While truck builders have demonstrated through various projects that aerodynamic integration is worth pursuing, the business dynamics of the trailer industry have precluded many of those manufacturers from investing heavily in the requisite research and development.

Such marriages of efficiency may eventually occur. But given those three hurdles to overcome, they’ll be driven more by the shotgun persuasion of federal regulation, not the desire of the marketplace.

Nonetheless, truck and trailer OEMs have not been waiting for a mandate to be issued to get cracking on how integrated aerodynamics can deliver substantial fuel savings. The biggest example is the involvement of truck builders in the Dept. of Energy’s (DOE) Super Truck program. This joint public/private partnership seeks to significantly boost commercial-vehicle fuel efficiency while maintaining current exhaust emissions levels. The project’s goal is to demonstrate a 50% improvement in overall freight efficiency on a Class 8 tractor-trailer measured in ton-miles per gallon.

According to Roland Gravel, head of the DOE Vehicle Technologies program, 40% of that goal will come from engine efficiency improvements and 60% from other improvements, including aerodynamics. To be clear, trailers are not covered at all under the existing rules to reduce the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of commercial vehicles by improving their fuel efficiency, measured in miles per gallon (MPG).

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHSTA), the two agencies that promulgated the current GHG/MPG rules, trailers have not yet been addressed by a rulemaking because of “the first-ever nature of this program and the agencies’ limited experience working in a compliance context with the trailer manufacturing industry.

“However,” the agencies added unequivocally, “because trailers do impact the fuel consumption and carbon dioxide emissions from combination tractors, and because of the opportunities for [carbon dioxide] reductions, we intend to include them in a future rulemaking.”

“EPA and NHTSA are currently developing the next phase of GHG/fuel-efficiency rules, which are unlikely to take effect before 2020, due to the rulemaking processes and mandated lead-time requirements both under the Clean Air Act and under the Energy Independence and Security Act,” advises Sean Waters, director of regulatory & product compliance for Daimler Trucks North America (DTNA). “As part of that development, the agencies are studying the means of regulating trailers.”

Trucks at work

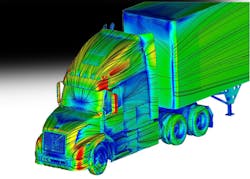

DTNA does extensive design and development in our in-house wind tunnel and with other tools including computational fluid dynamics and on-road testing, focusing on the interaction between the tractor and the trailer,” relates Waters. “For example, the Cascadia Evolution’s 20-in. side extenders and chassis side fairing improvements were designed to optimize air flow around common trailer configurations.

“Also, the Super Truck program is taking a longer view through theoretical and applied research for improving aerodynamics on both the tractor and trailer,” points out Waters.

“The program started by conducting a ‘basic shape analysis’ to determine the most aerodynamic form for a conventional tractor-trailer,” he continues, “while staying within basic tractor and trailer constraints (dry van volume, boat tail length, conventional cab dimensions).”

He says that basic shape has evolved into a “practical and functional tractor-trailer design while maintaining a low drag value. The aerodynamic performance of Super Truck can only be achieved by taking a combined tractor/trailer approach, since the strategy for optimizing airflow across the tractor greatly influences how air behaves downstream on the trailer.”

Despite all the work DTNA has done on integrating aerodynamics, Waters advises that “trailer aero equipment is currently available in the market and at this time, we do not have plans to develop or distribute a proprietary system.”

According to Wade Long, director of product marketing, Volvo Trucks’ “ongoing work to refine the aerodynamic properties of our vehicles considers the whole combination, tractor and trailer. Computational fluid dynamics and wind-tunnel testing help us develop features that will work in concert to improve aerodynamics of the combination.

“In recent years,” he continues, “we’ve introduced a number of aerodynamic enhancements to help improve the flow of air around the tractor and trailer. For example, in early 2011, Volvo Trucks introduced advanced aerodynamic components for VN model highway trucks. New exterior [aerodynamic] components included redesigned mirror heads with aerodynamic shrouds and arms, redesigned hood mirrors that also increase visibility, as well as additional ‘ground effect’ features below the bumper and side fairings. And a more aerodynamic roof fairing and sun visor were also added to VN day cab models.”

Looking ahead

Navistar continues to look at improvements in aerodynamics, and this does take into consideration the tractor as well as the trailer,” advises Elissa Maurer, manager of external communications. “Our Project Horizon [demonstration-vehicle] initiative is considering a number of new technologies, which include advanced powertrain, ergonomic and aerodynamic technologies that we intend to introduce in the next 24 to 36 months.

“Earlier this summer, President Obama announced his Clean Action Plan, which said his administration will partner with industry leaders to develop post-2018 fuel economy standards,” Maurer notes.

“Navistar continues to be actively engaged in providing solutions for improved fuel efficiency and reduced greenhouse gas emissions, but we do not have any timing yet for GHG rules specific to new trailers,” she advises. “And we’ve not yet made any announcements specific to combined tractor and trailer aerodynamics.”

According to Peterbilt’s chief engineer, Landon Sproull, the OEM partnered with Utility Trailers in the DOE Super Truck program to develop a tractor and trailer designed in combination to achieve “even higher” aerodynamic performance.

“Last year, we built our first-generation Super Truck using our Model 587 [tractor], which proved to exceed all of our aerodynamic performance targets,” he relates. “This year, we are testing and evaluating our second-generation Super Truck, which includes a Model 579. Both of these vehicles are equipped with advanced technologies that are helping optimize fuel economy and aerodynamic performance with a truck-trailer combination in real-world conditions.”

In addition, Sproull says that Peterbilt is “complementing those efforts with discussions with many other trailer manufacturers to improve overall aerodynamic efficiency to benefit the industry as a whole—for both current and future product offerings.”

Sproull hastens to add “that the trailer market is quite different than the truck market in that the trailer-to-truck ratio is, at a minimum, 4 to 1. That makes it more expensive for fleets to upfit trailers with aerodynamic components simply due to volume. Additionally, trailers are often not pulled by the same tractor or brand of tractor. With that said, there are elements that can benefit fleets and we continue to explore the best options to accomplish this.

“We have a good sense for what is possible, based on the DOE Super Truck project,” he adds. “However, as with all new technologies, the trick will be bringing these new systems and components to market with the best possible ROI [for fleet owners].”

Sproull notes that the GHG Phase II [trailer] regulations are only now being researched by the two agencies. “Until the preliminary ruling is published, it is uncertain when the content and effective [enforcement] date will be known.”

Dick Giromini, president & CEO of trailer maker Wabash National, speaking at a Heavy Duty Manufacturers Assn. seminar held this spring, advised there is growing recognition that “trailer makers can help improve fuel economy, too.”

He specifically cited the ability of trailer builders to optimize total vehicle weight, including the weight of aerodynamic devices added to help save fuel.

But Giromini also said more work will be done to minimize the tractor-trailer gap to improve fuel efficiency and that he expects more buyers will move, of their own accord, to spec full-trailer side skirts to enhance aerodynamics.

Fine print

The handwriting as to where EPA and NHTSA are eventually headed with a truck-trailer rulemaking has actually been on the wall for some time. Per the agencies’ draft regulatory-impact analysis, “Trailers for use with HD [heavy-duty] tractors are an important aspect of the GHG emissions performance of combination tractors and are estimated to be responsible for 11 to 12% of fuel consumed by Class 8 combination tractors. Optimizing the tractor and trailer as a system allows designers to take full advantage of the GHG emissions reduction opportunities.”

And the final regulatory-impact analysis the agencies issued declared that “NHTSA and EPA agree that the regulation of trailers, when appropriate, is likely to provide fuel efficiency benefits. We continue to believe that both agencies must perform a more comprehensive assessment of the [capabilities of the] trailer industry, and therefore that their inclusion at this time is not feasible.” The key words in that statement being “at this time.”

“Until that time,” the agencies went on, “the [EPA] SmartWay Transport Partnership Program will continue to encourage the development and use of technologies to reduce fuel consumption and CO2 emissions from trailers.”

From there, the impact analysis points to how the SmartWay program has “demonstrated that adding aerodynamic features to van trailer designs and the use of low rolling resistance tires can substantially reduce fuel consumption from tractor-trailers.”

But the agencies also admitted the challenges inherent in writing an effective GHG/MPG rule that would encompass trailer design: “The ratio of the number of trailers in the fleet relative to the number of tractors in the legacy fleet is typically three-to-one. At any one time, two trailers are typically parked while one is on the road. For certain private fleets, this ratio can be greater, as high as six-to-one. This characteristic of the fleet impacts the cost-effectiveness of trailer technologies because a trailer on average will only travel one-third of the miles traveled by a tractor.”

The upshot

The kicker is that EPA and NHTSA then remarked that “we have strong reason to believe that these [GHG and fuel-consumption] reductions would not occur absent regulation as noted in the recent NAS [National Academies of Science] report.”

The agencies then quote that report’s essential finding:

A perplexing problem for any option, regarding Class 8 vehicles, is what to do about the trailer. The trailer market represents a clear barrier with split incentives, where the owner of the trailer often does not incur fuel costs, and thus has no incentive to improve aerodynamics of the trailer itself or to improve the integration of the trailer with the tractor or truck. In other words, trailers affect the fuel efficiency of shipping, but they do not face strong uniform incentives to coordinate with truck owners. In principle, if truck owners had the ability to choose what trailers they accepted, they could require trailers with fuel-saving technologies; in practice, though, truck owners have limited practical ability to be selective about what trailers they accept.”

In other words, the view from Washington is that to truly advance the state of the art of tractor-trailer aerodynamics, a federal rulemaking is in order.

It’s true that it will take some time for EPA and NHTSA to come up with that rulemaking. As noted earlier, it’s unlikely any such rule will come into effect sooner than 2020. But truck and trailer makers are certainly on notice that it is only a matter of a relatively few years before a rule will be issued.

The big question, then, is not when, but what? What a GHG/MPG rule for trailers will require remains very sketchy, especially given that EPA and NHTSA jointly admit to the everyday facts of life about trucks and trailers that will make coming up with a workable rule difficult, to say the least.

Will the rule perhaps only go so far as to mandate a certain minimum aerodynamic performance for trailers? Or will it somehow require tractor builders and trailer makers to aerodynamically “fit” their vehicles together in some sort of integrated manner that’s hard to imagine today?

Time will tell. And soon, which is why heavy-duty vehicle designers seem to have integrated aerodynamics all over their drawing boards.