EPA targets key compounds for refrigerated cooling systems, trailer insulation

An advanced degree in chemistry might not be required to understand the Environmental Protection Agency’s latest push to protect the ozone layer and combat global warming, but it certainly helps. The layman’s takeaway for trucking is that key compounds used in refrigerated transport cooling systems and trailer insulation are scheduled to be prohibited, and the likely replacements are either more expensive, less effective or both.

EPA on Wednesday released the final rule specifying the details of its updated Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP), a program that is designed to evaluate and regulate substitutes for chemicals that are being phased out under the Clean Air Act (CAA) and the Obama administration's Climate Action Plan (CAP).

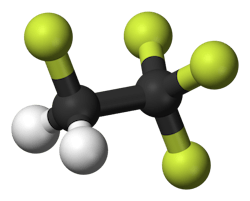

While the first two rounds of SNAP focused on ozone depletion, the third iteration takes aim at climate change and targets emissions of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), explains Robert York, strategic marketing manager for Dow Polyurethanes.

Among other changes, the SNAP plan calls for the elimination of the use of specific HFC “blowing agents,” which refrigerated trailer manufacturers use in polyurethane insulation.

The current blowing agents—the chemical compounds that put the “bubbles” in the foam, specifically HFC 134a and 245fa—that are scheduled to be eliminated do indeed have substantially higher potential negative impact rates on release to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide (CO2), York adds. However, he also points out that the percentage of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is miniscule.The good news for trucking is that there are “quite a few options,” though each has “strengths and weaknesses,” York notes. Hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) compounds can deliver even better insulation at the same thickness as current formulations, but will be much more expensive. Hydrocarbon (HC) compounds are less expense, but also have less insulating value, meaning additional thickness and weight.

A refrigerated trailer currently comes with about 1,000 pounds of foam insulation, he adds. And York also emphasizes that any simple explanation “has lots of caveats.”

“It’s not nearly as black and white as I might make it sound. There’s a lot of chemistry that will make HCs perform a little bit better, or you can try to cheapen an HFO formulation,” he says. “It’s really complex science at the heart of formulating these foams for trailers.”

For these HFCs and the application, EPA’s proposed rule set Jan. 1, 2017 as the date the prohibition would take effect. Dow and others, in the more than 7,500 comments submitted, argued that a Jan. 1, 2020 timeframe would be more realistic. A delay would give the industry enough time to come up with the best formulations, to build some trial trailers and put some miles on them, and to make any adjustments needed before going into full production, York explains.

Utility Trailer Mfg. Co., the country’s largest producer of reefer freight trailers at more than 20,000 a year, also argued that the 2017 date was “not feasible.” In its comment, filed last summer, Utility said its foam supplier had only recently provided a new compound for evaluation. The foam was “unacceptable” in a number of areas, and “did not meet the required minimums to demonstrate long-term stability.” Tests were underway on a more expensive formulation, the company noted, but early results again showed problems.

“Even if Utility and foam suppliers had foam formulations that already had passed the lab trials and were ready for building the required refrigerated test trailers (which, as noted above, is not the case), those trials could not commence for 6 to 12 months,” the comment says. “Using this timetable, the production trials on limited customer trailers could start by the first quarter of 2016 and complete no sooner than 2019 for the initial production runs, and 2020 for the latter productions runs.”

And EPA listened, opting for the 2020 implementation date.

Additionally, as EPA cites in the final rule, a number of comments stated that the proposed rule would result in increased energy consumption, potentially negating the overall net GHG emission reductions. Cost, likewise, was a concern.

“Although cost is not a consideration in our decision to change the status of certain substitutes, we note that based on technical concerns, the final rule establishes a later change of status date in a number of end-uses, which will allow manufacturers to spread costs over time,” the final rule states.

Similarly, the new SNAP rule covers refrigerants. Both Ingersoll Rand (parent company of Thermo King) and United Technologies (Carrier Transicold) noted the range of applications within the refrigerated transport sector and market complications, and asked for a 2020 implementation, rather than Jan. 1, 2016 as proposed.

About the Author

Kevin Jones 1

Editor

Kevin has served as editor-in-chief of Trailer/Body Builders magazine since 2017—just the third editor in the magazine’s 60 years. He is also editorial director for Endeavor Business Media’s Commercial Vehicle group, which includes FleetOwner, Bulk Transporter, Refrigerated Transporter, American Trucker, and Fleet Maintenance magazines and websites.