Trucking cautious, environmentalists aggressive in GHG hearing

CHICAGO. Too much? Not enough? The lines were clearly drawn between trucking industry representatives and environmental groups testifying in a public hearing convened to discuss the next round of fuel efficiency standards and greenhouse gas (GHG) limits for commercial vehicles. The 600-page proposed rule has been developed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Highway Safety Administration (NHTSA), who organized the Thursday session here.

The good news: Despite the complexity of such a regulation, the two sides support the government’s effort to come up with a workable solution that will benefit the trucking business and consumers along with the environment.

But, based on the morning session testimony of truck, engine and trailer builders, the key is to come up with a manageable framework that reflects the diversity of commercial vehicle applications—and with making sure new vehicles under the coming standards are both affordable and reliable. Additionally, any regulation should be applicable in all 50 states and should not impose changes on Phase I of the rule, to which manufacturers have already committed their production plans.

“In all candor, we still are studying the details of today’s massive proposal,” said Jed Mandel, president of the Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association (EMA). “We are focused on making sure that the final rule ‘gets it right.’”

Indeed, under the Department of Energy’s “SuperTruck” initiative, prototype vehicles have achieved “innovative, game-changing improvements in freight efficiency,” Mandel added. Yet, based on EMA’s preliminary assessments, even those SuperTrucks—which include technologies and design elements unlikely to commercially viable in 2027—wouldn’t meet the best-performing vehicle requirements under the proposed rule.

“We don’t believe that EPA’s and NHTSA’s intent is to adopt rules that would require the development of new technologies, beyond the SuperTruck prototypes just now being developed, as the reference for compliance with Phase II,” Mandel said. “Accordingly, we believe that it is necessary to refine the reference assumptions, and correct many of the underlying assumptions about technology penetration rates for certain market segments, in order to finalize a technologically feasible and implementable rule.”

Consider real-world applications, costs

Similarly, Eric Jorgensen, chairman of American Truck Dealers (ATD), emphasized that “doing this rule right is much more important than doing it quickly.” And, in explaining the importance of fuel economy to truck buyers, he even questioned “what market failure is the administration trying to fix?”

He also recalled the problems associated with EPA truck emissions rules in 2002, 2007 and 2010.

“Prospective customers will avoid, like the plague, vehicles they perceive will be less reliable. Cleaner, greener new equipment will do nothing for the environment or for energy security until it is bought and placed into service,” Jorgensen said. “Your goal should be to hit a regulatory ‘sweet spot’ by setting performance standards that result in new products that purchasers are willing and able to buy. In order to work, [the proposed standards] must pass economic muster.”

Of course, fuel efficiency is just one component of freight efficiency, as Wabash National Senior Vice President and General Counsel Erin Roth testified, and she called for “complementary programs and funding” to improve highways and maximize tractor-trailer capacity.

As a trailer manufacturer to be included under Phase II, Wabash is concerned that they “have very little leverage” in determining what components customers want and need on trailers, and that a semi-trailer is “more than just a box on wheels.” As with trucks, trailer customers need equipment and any add-ons to be reliable and cost-effective.

And, she pointed out, not all carriers and trailer types—such as tankers and flatbeds—benefit from fuel efficient technologies. And while Wabash supports proposed exemptions for that equipment, Roth called for additional waiver options, depending on application.

She also called for federal incentives, specifically exemptions from federal excise taxes on truck equipment and truck weight limits.

Christopher Hess, director of public affairs for Eaton, asked for “clear and realistic targets,” and he credited the success of Phase I to its “sound regulatory framework.” He called on EPA and NHTSA to “please stick with the model,” and that includes separate engine and vehicle standards, and a “powertrain test.”

“Deep engine and transmission integration, dual-clutch technology, and ultra-efficient transmissions are cost-effective ways to save fuel and achieve compliance without adding the weight, cost and complexity of some of the new and untested technologies,” Hess said.

No time to waste, environmentalists say

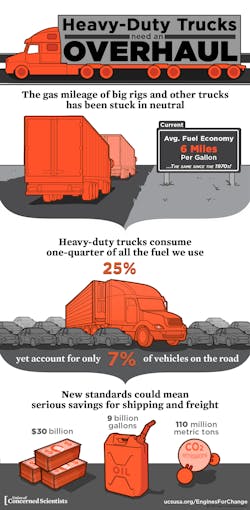

Since commercial vehicle use is outpacing the growth in passenger car travel, representatives of organizations that focus on the importance of addressing climate change argued that the trucking industry is capable of doing more, and sooner, than EPA and NHTSA propose as the leading option.

Instead, they pushed for “Alternative 4” under the proposed rule—which would achieve the same performance as the proposed standards two to three years earlier. And while, the rule itself notes, Alternative 4 is potentially achievable, the agencies have “outstanding questions” regarding the risks and benefits of the tighter timetable.

Still, “as proposed, the heavy truck fuel efficiency and greenhouse gas standards are an important step forward, but they fall short of being the strong standards our nation needs,” said Jason Mathers of the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

Specifically, along with a 2024 implementation date, EDF would like to see a tougher engine standard. Mathers suggested that existing technologies have the potential to cost-effectively reduce engine fuel consumption by more than 15% beyond the 2017 levels.

EDF also questioned “the ability of natural gas trucks to deliver real-world greenhouse gas reductions,” particularly with regard to methane leakage. “The requirements that natural gas engines have closed crankcases and the establishment, for the first time ever, of hold-time requirements for LNG fuel tanks, are important,” Mathers said.

Likewise, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) argued that the engine standards “are too low,” and undermine overall savings.

“The 4.2 percent improvement in efficiency over a 10 year span is dramatically lower than the pace of improvements already achieved by manufacturers under the Phase 1 standards, and it does not reflect the level of improvement already being achieved in manufacturers’ R&D projects,” said Dave Cooke, UCS vehicles analyst. “This has resulted in an extremely conservative engine standard, one which is roughly two to three times lower than what could be accomplished by 2027.”

UCS contends the average fuel consumption from new trucks could be reduced 40 percent, compared to 2010, by 2025, and that the technologies to do so are either already in the marketplace or could be “well before 2024.”

Luke Tonachel, director of the Clean Vehicles and Fuels Project for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), also pushed for the 2024 deadline and for stricter engine standards that would be “technology-forcing.”

“When it comes to cutting carbon and reducing our dangerous dependence on oil, every year counts,” Tonachel said.

In addition to an afternoon session Thursday in Chicago, a second public hearing will be held in Long Beach, CA, Aug. 18.

About the Author

Kevin Jones 1

Editor

Kevin has served as editor-in-chief of Trailer/Body Builders magazine since 2017—just the third editor in the magazine’s 60 years. He is also editorial director for Endeavor Business Media’s Commercial Vehicle group, which includes FleetOwner, Bulk Transporter, Refrigerated Transporter, American Trucker, and Fleet Maintenance magazines and websites.