BIRMINGHAM. For-hire carrier execs probably shouldn’t worry so much about the latest “Uber for trucking” start-up company from Silicon Valley—they need to worry about Uber itself, cautions supply chain analyst Adrian Gonzalez.

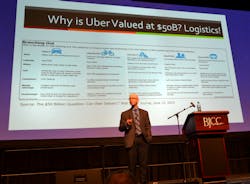

The president and founder of Adelante SCM, who works with manufacturers and shippers to improve product delivery, suggested that Uber isn’t valued at more than $50 billion because it's a “taxi app.”

“It’s really because of lot of the investors see Uber as a logistics company,” Gonzalez said, pointing to slide that showed a range of logistics-related projects Uber has under way. “For those of you who think that Uber is not a carrier, this is an emerging competitor.”

The comments Tuesday were part of a wide-ranging presentation on emerging trends and technologies in freight transportation, offered before more than 1,000 attendees and exhibitors at the McLeod Software 2015 Users’ Conference here.

Amazon, likewise, has recently announced its “Amazon Flex” model, which relies on non-professional “every day folks” to make local deliveries, he noted.

“The reality is that there are different models evolving in terms of how to get product from Point A to Point B, beyond the traditional roads and the companies that you represent,” Gonzalez said.

Of course, Amazon has made headlines with its highly publicized development of a drone delivery system. But Gonzalez discounts the threat of significant use of parcel drones any time soon, characterizing the technology as “prototype,” based largely on the operational limitations of current aircraft designs and weather challenges, as well as limited benefits and potential regulatory roadblocks. He does anticipate a role for drone delivery in developing nations, however, where the lack of a traditional transportation infrastructure presents opportunities—similar to the way in which some remote regions embraced cellular telephone technology before landlines were ever installed.

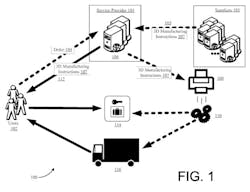

Even more recently, Amazon in February filed a patent application for a system that would use 3-D printers installed on trucks to process and manufacture orders en route to the buyer. And, unlike delivery drones, 3-D printing is an established technology that’s only recently enjoyed wider adoption.

Still, while the potential exists for creating a consumer society “where everyone is a manufacturer,” Gonzalez suggests the better application will be “mass customization, not mass production.” He cites the use of 3-D printers to create made-to-fit knee replacements, and in the process to replace the need for a billion-dollar inventory of assorted knee parts that are shipped back and forth between the supplier and hospitals as doctors pick the correct pieces from kits and return the leftovers.

Indeed, predicting the future, more than a few years out, is “a dangerous game.”

“The only thing we know for sure is that we’ll be wrong—whatever we envision today is going to be drastically different than what becomes reality 5 or 10 or 20 years from now,” he said.

As Gonzalez details, no one can be certain of even the freight basics: What will be shipped? From where? To where? How?

The supply chain buzzword for the conference has been “omnichannel,” or the need for retailers to offer products online, via apps, and in stores. And that impacts where goods will be shipped from. Along with the use of distribution centers and direct-from-factory shipping, traditional big-box retail stores will emerge as “mini warehouses,” from which goods will be delivered locally. Malls are dying.

“What is the most cost-effective way for us to get the product in the least amount of time to the customer? This is a puzzle that most, if not all, retailers are still trying to figure out,” Gonzalez said. “This is not only a transportation question, it’s an inventory management question; it’s a labor question. A lot of them still haven’t figured out the right balance.”

With next-day delivery already emerging as the default expectation, increasingly consumers will demand more precise delivery windows—and, at least in terms of dwell times at shipping docks, this could benefit carrier utilization metrics, he added.

On a broader level, the freight impact of globalization will depend on the location of cheap labor, on international trade deals, and tax policy.

Gonzalez emphasized the need for supply chain professionals to model for a variety of possibilities, and to run network analyses to stay ahead of the curve, to have the right resources in the right places for the road ahead. While planners may have a reasonable idea of what to expect, the next new really big thing is hard to anticipate—if not impossible.

“Don’t be quick to dismiss upstarts and some of these technologies. The last thing you want is to be surprised and be disrupted by a new entrant or new technology in the industry,” he said. “I could be completely wrong about all of this stuff, but one or two things might be right.”

About the Author

Kevin Jones 1

Editor

Kevin has served as editor-in-chief of Trailer/Body Builders magazine since 2017—just the third editor in the magazine’s 60 years. He is also editorial director for Endeavor Business Media’s Commercial Vehicle group, which includes FleetOwner, Bulk Transporter, Refrigerated Transporter, American Trucker, and Fleet Maintenance magazines and websites.