Wearable technologies—or more simply “wearables,” the new word that’s emerged to reference them—carry the promise of the next level in technological advancement, bridging the gap between humans and electronic device interactivity and information flow. But much of the energy surrounding wearables remains potential rather than kinetic, and the tech hasn’t yet brought on the mass adoption and idiomatic sea change that smartphones have, for example.

So are wearables just more trinkets to charge up every night that work in parallel to devices already out there, or —as some believe—could they actually revolutionize the world of trucking and transportation?

To answer that, start by mapping out the categories of wearables that have reached the market. Kelly Frey, vice president of product marketing at telematics and fleet management technology company Telogis, breaks them down this way: fitness trackers, wearable cameras, smart watches, GPS location-tracking devices, and augmented reality eyeglasses that can show users a virtual “layer” or other information in addition to the real world they can view.

And many wearable devices cross into several of those categories. It shows the challenge wearables face, experts tell Fleet Owner, which isn’t so much in technologically “doing” as it is in finding the best functional combinations to be relevant. That’s the opposite situation smartphones had. Those already filled the core telephone function users needed and added things like Internet access, touch screen displays, and instruments such as accelerometers and cameras to unlock huge potential for software applications, user interfacing, and new capabilities that developers aren’t even close to exhausting yet.

Wearables come from the other direction. The routine in their case is to make a device that can be worn and pack enough features into it to make it a “must-have” item that sparks a watershed of consumer and/or business purchasing. And that hasn’t really happened yet for wearable technology, notes Christian Schenk, president of transportation technology consulting firm CLS LLC.

"Consumer adoption of what we'll call a 'smart wearable' with apps and all those kinds of things is still quite low, and trucking is no different," he says. "Fleets aren't going to rush out there and spend $300 to $400 or so on a watch to give to their drivers, and I don't think the value is there enough for the consumer to run out and get it."

Schenk notes, however, that there’s been strong growth in fitness-tracking wearables such as Fitbits, which can measure things like steps taken, calories burned and heart rate and pair the information via wireless connectivity with computer or smartphone apps. Even so, “I just don’t see the health-conscious trucker yet,” he contends, adding, “I truly think that in trucking, the wearables category is premature.”

By and large, Schenk emphasizes, that’s because wearables have to compete against the ever-growing use of smartphones. “If you’re 10 years old to 80 years old, you have a smartphone and you use it every day,” he asserts, “and that’s only going to become more ubiquitous.” For trucking technology companies, he says, “if you want access to the market and to the masses, you’re building something to run on a phone, simple as that.”

Aside from the success of fitness trackers, the next-most prominent wearable technology so far has been the smart watch. Companies like Apple and Samsung have released multiple models and generations of their watches, showcasing smartphone-like or extending capabilities and bolstering the watches with big-dollar, sleek ad campaigns. But Dominique Bonte, vice president for business-to-business at technology and business intelligence consultancy ABI Research, says many consumers have yet to be convinced, even those who’ve made a purchase.

“People are still trying to figure it out,” Bonte tells Fleet Owner. “I’ve come across many people who’ve bought the Apple Watch, and the answer I get from them is, ‘Hmm, I haven’t actually figured out why I need it yet.’”

Inroads

That very sentiment—where there’s interest and seemingly lots of potential for wearables—describes the situation for wearables in trucking. Despite the apparently uphill battle they face, several types of wearables have made inroads. Fleet management and telematics technology company PeopleNet began releasing software apps last year for Android-based or Apple smart watches, in one example, allowing drivers to do things like send or receive messages via their trucks’ telematics and communications system.

“The idea is to untether the driver from the truck so they can get needed information or communication more easily and conveniently,” says Randy Boyles, senior vice president of mobile strategy at PeopleNet. Meanwhile, Apple and Telogis also recently announced a partnership and are working to develop new applications, and Telogis’ Frey says that in itself is telling.

“The fact that a company like Apple is taking an interest in the trucking and transportation sector to me is very encouraging,” he notes. “What we’re doing with Apple is trying to improve the commercial or mobile worker’s life with technology.”

Frey says that a key with wearables in trucking is driver acceptance. Remember those virtual or augmented reality glasses, perhaps like the Google Glass Experiment that the company seemed to leave at the wayside in early 2014? Even with all its potential, that product faced many doubts and questions; regulators feared it would distract drivers, ABI Research’s Bonte notes, or people were concerned about how it was being used.

So Telogis has taken that lesson to heart with smart watches, Frey says. “It’s not just the fact that we can have the technology, but will drivers use it? Will they push back on it? What are we trying to do with it?” he ponders.

The first product that Telogis released for use with the Apple Watch was Telogis Coach, an app that taps info from the truck’s telematics system such as instances of hard acceleration, hard braking, and on-time arrivals to rate the driver’s performance in those categories against his or her peers, a take on what’s typically called “gamification.”

And in this use, while the company has enabled similar driver scorecards in various forms for years, Frey says Telogis has seen a “huge impact” with drivers getting the information on an Apple Watch. It’s proven easier than other devices for drivers to glance at whenever they get a chance and has more effectively fueled healthy competition among them to get the best scores, he explains.

Also, the haptic feedback—tactile communication, in this case by vibrating at different intensities and in pulses—that smart watches like the Apple Watch have, combined with other data instruments and the particular location on the wrist, may be critical to the success of the smart watch in the transportation industry, Frey says.

For instance, those features would allow a smart watch to work with a vehicle’s telematics system data to provide vibration-based danger alerts to a driver about to make a lane change with a car in his or her blind spot. The watch similarly could send a vibration/auditory alert if a truck or trailer door is opened while the driver is parked and resting for the night, signaling a possible break-in.

Bonte points out that smart watches can be made to communicate without the user having to look at them or provide any input. He gives the example of one pedestrian navigation app for smart watches that theoretically could also have applications in trucking and transportation. “It’s easier than pulling out your phone,” he tells Fleet Owner. “It vibrates once for you to go left and twice for you to go right, so you don’t necessarily have to look at it.”

A ruggedized pendant-type wearable device is also in use by some fleets that face inherently greater risks such as oilfield haulers, says Jim Rodi, general manager of the North American oil and gas services division at Trimble, PeopleNet’s parent company.

“We call it the Personal Safety Monitor,” Rodi explains. “It’s really for lone-worker, possibly ‘man-down’ types of situations where if something goes wrong, the worker depresses a button on the pendant, which sends a message back through the vehicle’s modem and then sends a distress signal to the back office.”

The smart watch could take that concept even further, Frey suggests. A watch is worn just as conveniently as a pendant, and in addition to vibration alerts or warnings could feature onscreen “buttons” a trucker could tap to alert the back office or even call 911. A smart watch also could issue a distress call without any driver input, he adds: if a driver were to pass out and fall, for example, while making a delivery, the watch’s accelerometer could detect the force and sudden change, similar to an “I fell and can’t get up” warning device.

If you want more proof of the smart watch’s assimilation in trucking, Bonte notes that Swedish commercial truck OEM Scania issued and sold out its own limited-edition smart watch, the Black Griffin Scania Watch, which was based on a Sony SmartWatch 3.

“To us, it makes perfect sense,” a narrator in a commercial Scania produced for the watch states. “This is much more than a watch; it’s the first part of your truck that you can wear, a stylish tool that helps you keep track of fuel consumption trends, how to optimize your driving efficiency, and naturally, when it’s time to work and when it’s not.”

A revolution?

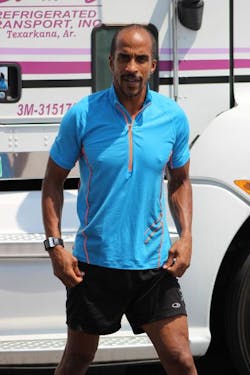

When it’s time to work and when it’s not—currently defined for commercial truck drivers by federal hours-of-service regulations—may be exactly how wearables bring transformational change to the trucking industry, agrees Schenk, Bonte and Frey, all of them noting the biometric readings that wearables make possible. Fleet Owner turned to one of the industry’s best-known fitness experts, Fitness Trucking founder and former Prime Inc. driver Siphiwe Baleka, to hear about one specific device that could do it.

Baleka says he’s disappointed in the biometric performance of most available wearables like Fitbits and the Apple Watch, which tend to use optical LEDs to track heart rate, for their unreliable use with his high-intensity workout program designed specifically for truck drivers. “If you’re going from push-ups to mountain climbers to burpees—if your wrist position is constantly changing—the optical sensors don’t do very well,” he contends.

However, he says Fitness Trucking is working with Canadian tech company Fatigue Science to test the watch-like Readiband’s potential use in trucking. Fatigue Science claims the product is “the world’s most accurate wrist-worn sleep detection device,” and the technology has been used with soldiers, elite athletes and others.

According to Baleka, Readiband monitors and translates sleep patterns into fatigue readouts that indicate the user’s impairment just like being drunk. “With this product, which I like to call the ‘Fatiguealyzer,’ I think in the future we’ll do away with hours-of-service regulations. We won’t even have them. Hours of service is an equation that’s not based on anything real; if the real instrument is fatigue, why not measure it directly?” he tells Fleet Owner.

“What will happen is a driver will be able to drive as long as he stays above the [fatigue] threshold of, say, 70% on this device, which is the functional equivalent of a 0.08% blood alcohol content you’d read with a breathalyzer,” Baleka contends.

“Now, all of a sudden, it’s going to put a premium on drivers who are in better health, who better manage their time, who better manage their sleep environment, and practice good sleep hygiene,” he continues. “Imagine you wake up in the morning and have to see if you’re fit to drive based on your actual fatigue level. Even though there will be a lot of resistance to this, it will change the industry, because the driver who’s healthier, better manages his time and better manages his sleep will get what? More opportunity to drive and make money.”

That also would be in the best interest of shippers and receivers, Baleka adds, because they’d see that a carrier is taking steps to reduce the risk of freight loss or damage. And carriers could use the driver fatigue information as real data to support contract clauses to allow leeway in delivery/pickup appointments.

“Just like it’s illegal to force a driver to drive over the speed limit to deliver a load, it’s already illegal to make a driver drive when he’s fatigued,” Baleka says. “That law’s already on the books; we just had no way of defining or enforcing it.” He views real-time, biometrically gathered fatigue data as “the game-changer” for wearables in trucking and transportation.

Perhaps it will be, but the kite that catches the wind for wearables, so to speak, could be that or something else just around the corner. “I think we’re just at the very early stage of figuring out where all this stuff is going,” Telogis’ Frey sums up.

“I think if app developers like us and others come up with really unique use cases that benefit the carrier and help the driver—help him be safer, help him be productive, help him make more money—I think wearables will just become part of the fabric [of trucking and transportation], and I see the benefit of them,” he says.

About the Author

Aaron Marsh

Aaron Marsh is a former senior editor of FleetOwner, who wrote for the publication from 2015 to 2019.